User:Hisa312/東田納西

| 東田納西 | |

|---|---|

| East Tennessee | |

東田納西的位置 | |

| 國家 | |

| 州 | |

| 面积 | |

| • 陸地 | 40,000 平方公里(13,558.27 平方英里) |

| 人口(2020) | 2,470,105人 |

| • 密度 | 70.34人/平方公里(182.18人/平方英里) |

東田納西(英語:East Tennessee)是美國田納西州的東部大約三分之一的地區,是田納西州法律規定的三大分區之一。東田納西共有33個縣,其中30個位於北美東部時區,另外3個縣位於北美中部時區,分別是布萊德索縣、坎伯蘭縣和馬里昂縣。[1]東田納西完全位於阿巴拉契亞山脈內,但其地形從密集的山脈到寬闊的河谷均有。東田納西包括田納西州的第三大城市諾克斯維爾和第四大城市查塔努加,以及第六大人口中心三城。

南北戰爭期間,雖然田納西州加入了邦聯,但是許多東田納西人仍然忠於聯邦。在戰爭早期,一些忠於聯邦的南方聯合主義者,試圖將東田納西分裂為一個聯邦州份,但沒有成功。戰後,東田納西的城市開始發展工業。大蕭條期間,國會建立了田納西河谷管理局,刺激經濟發展,並幫助東田納西的經濟和社會現代化。現時,田納西河谷管理局的行政業務總部設在諾克斯維爾,其電力業務則設在查塔努加。橡樹嶺是世界上第一個成功進行鈾濃縮的地方,以製造世界上第一個原子彈,其中兩枚在第二次世界大戰結束時落在日本。[2]20世紀末,阿巴拉契亞地區委員會進一步轉變了東田納西。

東田納西在地理和文化上都是阿巴拉契亞的一部分。自20世紀初,東田納西均被定義屬於阿巴拉契亞。[3]美國國家公園中最多遊客的大煙山國家公園和數百個較小的休閒區都座落在東田納西。東田納西通常被認為是鄉村音樂的起源地,主要是因為1927年在布里斯托爾舉行的會議令一些音樂家更知名。[4]

地理[编辑]

與美國大多數州地區的地理名稱不同,東田納西一詞具有法律、社會經濟和文化意義。東田納西、中田納西和西田納西為田納西州的三個分區,其邊界由州法律定義。東田納西的陸地總面積為13,558.27平方英里(35,115.8平方公里),是田納西州的第二大區,僅次於中田納西。[5]東田納西的土地面積約佔田納西州土地總面積的32.90%。東田納西在地理和文化上是阿巴拉契亞的一部分,通常也被認為是上南方的一部分。[6]東田納西的東方為北卡羅來納州,東北方為弗吉尼亞州,北方為肯塔基州,南方為佐治亞州,西南角與阿拉巴馬州接壤。

根據慣例,東田納西州和中田納西州的邊界大致遵循東部和中部時區之間的分界線。不過位於中部時區的布萊索縣、坎伯蘭縣和馬里昂縣在法律上被定義為東田納西州的一部分,當中馬里昂縣曾被納入中田納西。塞夸奇縣曾被納入東田納西,現時在法律上是中田納西的一部分,但通常被認為是東田納西的一部分。一些位於中田納西的東北部的縣,包括芬特雷斯縣和皮克特縣,曾在南北戰爭期間支援聯邦,因此有時在文化上被認為是東田納西的一部分。

地形[编辑]

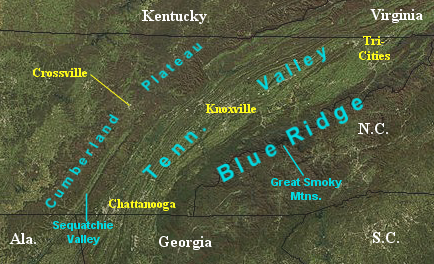

東田納西位於阿巴拉契亞山脈的三個主要地質劃分內,包括東部與北卡羅來納州接壤的藍嶺山脈、中部的嶺谷地區(大阿帕拉契山谷),以及西部的坎伯蘭高原,其中一部分位於中田納西州。坎伯蘭山脈的南端延伸到坎伯蘭高原和嶺谷地區之間的地區,而坎伯蘭高原和坎伯蘭山脈是阿巴拉契亞高原的一部分。[7]

田納西州和北卡羅來納州的邊界大部分由藍嶺山脈形成。藍嶺平均海拔5000英尺(1,500米),是田納西州海拔最高的地區。[8]藍嶺被細分為幾個子山脈:北部的Iron Mountains、Unaka Range和Bald Mountains、中部的大煙山,南部的Unicoi Mountains、Little Frog Mountain和Big Frog Mountain地區。[9]位於邊界的大煙山克林曼丘海拔6,643英尺(2,025米),是田納西州的最高點。[8]藍嶺大部分地區森林茂密,並被州和聯邦實體保護,其中最大的包括大煙山國家公園和切諾基國家森林。[10]阿巴拉契亞小徑在田納西州的一段大致沿著與北卡羅來納州的邊界,接著在羅安山附近完全進入田納西州,之後進入維吉尼亞州。[11]

嶺谷是東田納西最大、排名最低、人口最多的地區。它由一系列交替和平行的細長山脊組成,中間有寬闊的河谷,大致朝向東北到西南。田納西河位於嶺谷,在諾克斯維爾內霍爾斯頓河和法國寬河的交匯處形成,向西南流向查塔努加。東田納西州的最低點是田納西河進入馬里昂縣阿拉巴馬州的地方,海拔約600英尺(180米)。[12]田納西州上游流域的其他著名河流包括克林奇河、諾利丘基河、瓦陶加河、埃默裡河、小田納西河、希瓦西河、塞夸奇河和奧科伊河。嶺谷一些山脊比周圍大多數山脊高得多,通常被稱為山脈,包括克林奇山、海灣山和鮑威爾山。[10]

坎伯蘭高原比阿巴拉契亞山谷高近1000英尺(300米),從北邊的肯塔基州邊境延伸到南邊的佐治亞州和阿拉巴馬州邊境。[8] 它的平均海拔為2000英尺(610米),主要由平頂台地組成,不過北部略有崎嶇。[9][13]坎伯蘭高原還有許多被陡峭的峽谷隔開的瀑布和溪谷。[14]田納西分水嶺沿著高原西部延伸,將田納西河和坎伯蘭河的分水嶺分開。東田納西和中田納西大致在田納西分水嶺的兩邊分開。坎伯蘭縣、摩根縣和斯科特縣為東田納西的一部分,芬特雷斯縣、範布林縣和格倫迪縣,為中田納西的一部分。 Sequatchie山谷位於坎伯蘭高原東南部,是狹長而狹窄的山谷,大部分範圍位於東田納西州內。[a]Sequatchie山谷以東的高原部分被稱為Walden Ridge。 高原的一個值得注意的獨立部分是瞭望山,它俯瞰著查塔努加。[ 13]在查塔努加以西,田納西河流經田納西河峽谷的高原。

The Cumberland Mountains begin directly north of the Sequatchie Valley, and extend northward to the Cumberland Gap at the Tennessee-Kentucky-Virginia tripoint. While technically a separate physiographic region, the Cumberland Mountains are usually considered part of the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. The Cumberland Mountains reach elevations above 3,500英尺(1,100米) in Tennessee, and their largest subrage is the Crab Orchard Mountains. The Cumberland Trail traverses the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[16]

Counties[编辑]

The Official Tourism Website of Tennessee has a definition of East Tennessee slightly different from the legal definition; the website excludes Cumberland County while including Grundy and Sequatchie Counties.[17]

Climate[编辑]

Most of East Tennessee has a humid subtropical climate, with the exception of some of the higher elevations in the Blue Ridge and Cumberland Mountains, which are classified as a cooler mountain temperate or humid continental climate.[18] As the highest-lying region in the state, East Tennessee averages slightly lower temperatures than the rest of the state, and has the highest rate of snowfall, which averages more than 80英寸(200厘米) annually in the highest mountains, although many of the lower elevations often receive no snow.[19][20] The lowest recorded temperature in state history, at −32 °F(−36 °C), was recorded at Mountain City on December 30, 1917.[21] Fog is extremely common in East Tennessee, especially in the Ridge-and-Valley region, and often presents a significant hazard to motorists.[22]

Population and demographics[编辑]

| 歷史人口數 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 調查年 | 人口 | %± | |

| 1790年 | 25,030 | — | |

| 1800年 | 73,419 | 193.3% | |

| 1810年 | 101,367 | 38.1% | |

| 1820年 | 138,023 | 36.2% | |

| 1830年 | 196,357 | 42.3% | |

| 1840年 | 224,259 | 14.2% | |

| 1850年 | 260,397 | 16.1% | |

| 1860年 | 301,001 | 15.6% | |

| 1870年 | 332,547 | 10.5% | |

| 1880年 | 428,704 | 28.9% | |

| 1890年 | 543,091 | 26.7% | |

| 1900年 | 640,222 | 17.9% | |

| 1910年 | 732,471 | 14.4% | |

| 1920年 | 814,648 | 11.2% | |

| 1930年 | 960,133 | 17.9% | |

| 1940年 | 1,101,099 | 14.7% | |

| 1950年 | 1,288,886 | 17.1% | |

| 1960年 | 1,377,281 | 6.9% | |

| 1970年 | 1,486,765 | 7.9% | |

| 1980年 | 1,768,149 | 18.9% | |

| 1990年 | 1,832,138 | 3.6% | |

| 2000年 | 2,108,133 | 15.1% | |

| 2010年 | 2,327,544 | 10.4% | |

| 2020年 | 2,470,105 | 6.1% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[23] | |||

East Tennessee is the second most populous and most densely populated of the three Grand Divisions. At the 2020 census it had 2,470,105 inhabitants living in its 33 counties, and increase of 142,561, or 6.12%, over the 2010 figure of 2,327,544 residents. Its population was 35.74% of the state's total, and its population density was 182.18名居民每平方英里(70.34名居民每平方公里).[24] Prior to the 2010 census, East Tennessee was the most populous of the state's Grand Divisions, but was surpassed by Middle Tennessee, which contains the rapidly-growing Nashville and Clarksville metropolitan areas.

Demographically, East Tennessee is one of the regions in the United States with one of the highest concentrations of people who identify as White or European American.[25] In the 2010 census, every county in East Tennessee except for Knox and Hamilton, the two most populous counties, had a population that was greater than 90% White.[26] In most counties in East Tennessee, persons of Hispanic or Latino origins outnumber African Americans, which is uncommon in the Southeastern United States.[26] Large African American populations are found in Chattanooga and Knoxville, as well as considerable populations in several smaller cities.[26]

Cities and metropolitan areas[编辑]

The major cities of East Tennessee are Knoxville, which is near the geographic center of the region; Chattanooga, which is in southeastern Tennessee at the Georgia border; and the "Tri-Cities" of Bristol, Johnson City, and Kingsport, located in the extreme northeasternmost part of the state. Of the ten metropolitan statistical areas in Tennessee designated by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), six are in East Tennessee. Also designated by the OMB in East Tennessee are the Knoxville-Sevierville-La Follette, Chattanooga-Cleveland-Athens and Tri-Cities combined statistical areas.[27]

Knoxville, with about 190,000 residents, is the state's third largest city, and contains the state's third largest metropolitan area, with about 1 million residents.[28][29] Chattanooga, with a population of more than 180,000, is the state's fourth largest city, and anchors a metropolitan area with more than 500,000 residents, of whom approximately one-third live in Georgia.[28][29] The Tri-Cities, while defined by the Office of Management and Budget as the Kingsport-Bristol and Johnson City metropolitan areas, are usually considered one population center, which is the third-most populous in East Tennessee and the fifth-largest statewide.

Most of East Tennessee's population is found in the Ridge-and Valley region, including that of its major cities. Other important cities in the Ridge and Valley region include Cleveland, Athens, Maryville, Oak Ridge, Sevierville, Morristown, and Greeneville. The region also includes the Cleveland and Morristown metropolitan areas, each of which contain more than 100,000 residents. The Blue Ridge section of the state is much more sparsely populated, its main cities being Elizabethton, Pigeon Forge, and Gatlinburg. Crossville is the largest city in the Plateau region, which is also sparsely populated.

Most residents of the East Tennessee region commute by car with the lack of alternative modes of transportation such as commuter rail or regional bus systems. Residents of the metropolitan areas for Knoxville, Morristown, Chattanooga, and the Tri-Cities region have an estimated one-way commute of 23 minutes.[30]

| East Tennessee最大城市排名 Source:[28] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 排名 | 城市名稱 | County| | 人口 | ||||||

Knoxville |

1 | Knoxville | Knox | 190,740 |  Johnson City | ||||

| 2 | Chattanooga | Hamilton | 181,099 | ||||||

| 3 | Johnson City | Washington | 71,046 | ||||||

| 4 | Kingsport | Sullivan | 55,442 | ||||||

| 5 | Cleveland | Bradley | 47,356 | ||||||

| 6 | Maryville | Blount | 31,907 | ||||||

| 7 | Oak Ridge | Anderson | 31,402 | ||||||

| 8 | Morristown | Hamblen | 30,431 | ||||||

| 9 | Bristol | Sullivan | 27,147 | ||||||

| 10 | Farragut | Knox | 23,506 | ||||||

Congressional districts[编辑]

East Tennessee includes all of the state's 1st, 2nd, and 3rd congressional districts, and part of the 4th district. The First District is concentrated around the Tri-Cities region and Upper East Tennessee. The Second District includes Knoxville and the mountain counties to the south. The Third District includes the Chattanooga area and the counties north of Knoxville (the two areas are connected by a narrow corridor in eastern Roane County). The Fourth, which extends into an area southwest of Nashville, includes several of East Tennessee's Cumberland Plateau counties.

History[编辑]

Native Americans[编辑]

Much of what is known about East Tennessee's prehistoric Native Americans comes as a result of the Tennessee Valley Authority's reservoir construction, as federal law required archaeological investigations to be conducted in areas that were to be flooded. Excavations at the Icehouse Bottom site near Vonore revealed that Native Americans were living in East Tennessee on at least a semi-annual basis as early as 7,500 B.C.[31] The region's significant Woodland period (1000 B.C. – 1000 A.D.) sites include Rose Island (also near Vonore) and Moccasin Bend (near Chattanooga).[31][32] During what archaeologists call the Mississippian period (c. 1000–1600 A.D.), East Tennessee's Indigenous inhabitants were living in complex agrarian societies at places such as Toqua and Hiwassee Island, and had formed a minor chiefdom known as Chiaha in the French Broad Valley.[33] Spanish expeditions led by Hernando de Soto, Tristan de Luna, and Juan Pardo all visited East Tennessee's Mississippian-period inhabitants during the 16th century.[34] Some of the Native peoples who are known to have inhabited the region during this time include the Muscogee Creek, Yuchi, and Shawnee.[35][36]

By the early 18th century, most Natives in Tennessee had disappeared, very likely wiped out by diseases introduced by the Spaniards, leaving the region sparsely populated.[36] The Cherokee began migrating into what is now East Tennessee from what is now Virginia in the latter 17th century, possibly to escape expanding European settlement and diseases in the north.[37] The Cherokee established a series of towns concentrated in the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee valleys that became known as the "Overhill towns", as traders from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia had to cross "over" the mountains to reach them. Early in the 18th century, the Cherokee forced the remaining members of other Native American groups out of the state.

Pioneer period[编辑]

The first recorded Europeans to reach what is now East Tennessee were three expeditions led by Spanish explorers: Hernando de Soto in 1540–1541, Tristan de Luna in 1559, and Juan Pardo in 1566–1567.[38][39][40] Pardo recorded the name "Tanasqui" from a local Native American village, which evolved into the state's current name.[34] In 1673, Abraham Wood, a British fur trader, sent an expedition led by James Needham and Gabriel Arthur from Fort Henry in the Colony of Virginia into Overhill Cherokee territory in modern-day northeastern Tennessee.[41] Needham was killed during the expedition and Arthur was taken prisoner, and remained with the Cherokees for more than a year.[42] Longhunters from Virginia explored much of East Tennessee in the 1750s and 1760s in expeditions which lasted several months or even years.[43]

The Cherokee alliance with Britain during the French and Indian War led to the construction of Fort Loudoun in 1756 near present-day Vonore, which was the first British settlement in what is now Tennessee.[44] Fort Loudoun was the westernmost British outpost to that date, and was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm and constructed by forces under Captain Raymond Demeré.[45] Shortly after its completion, Demeré relinquished command of the fort to his brother, Captain Paul Demeré.[46] Hostilities erupted between the British and the Overhill Cherokees into an armed conflict, and a siege of the fort ended with its surrender in 1760.[47] The next morning, Paul Demeré and a number of his men were killed in an ambush nearby, and most of the rest of the garrison was taken prisoner.[48] A peace expedition led by Henry Timberlake in 1761 provided later travelers with invaluable knowledge regarding the location of the Overhill towns and the customs of the Overhill Cherokee.

The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 brought a stream of explorers and traders into the region, among them additional longhunters. In an effort to mitigate conflicts with the Natives, Britain issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains.[49] Despite this proclamation, migration across the mountains continued, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving in northeastern Tennessee in the late 1760s.[50][51] In 1769, William Bean— an associate of famed explorer Daniel Boone— built what is generally acknowledged as Tennessee's first permanent Euro-American residence in Tennessee along the Watauga River in present-day Johnson City.[52][53] Shortly thereafter, James Robertson and a group of migrants from North Carolina (some historians suggest they were refugees of the Regulator wars) formed the Watauga Settlement at Sycamore Shoals in modern-day Elizabethton on lands leased from the Cherokees. In 1772, the Wataugans established the Watauga Association, which was the first constitutional government west of the Appalachians, and the "germ cell" of the state of Tennessee.[54] Most of these settlers were English or of primarily English descent, but nearly 20% of them were Scotch-Irish.[55] In 1775, the settlers reorganized themselves into the Washington District to support the cause of the American Revolutionary War, which had begun months before.[56] The following year, the settlers petitioned the Colony of Virginia to annex the Washington District in order to provide protection from Native American attacks, which was denied. Later that year, they petitioned the government of North Carolina to annex the Washington District, which was granted in November 1776.[57]

In 1775, Richard Henderson negotiated a series of treaties with the Cherokee to sell the lands of the Watauga settlements at Sycamore Shoals on the banks of the Watauga River in present-day Elizabethton.[58] Later that year, Daniel Boone, under Henderson's employment, blazed a trail from Fort Chiswell in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap, which became part of the Wilderness Road, a major thoroughfare for settlers into Tennessee and Kentucky.[59] That same year, a faction of Cherokees led by Dragging Canoe— angry over the tribe's appeasement of European settlers— split off to form what became known as the Chickamauga faction, which was concentrated around what is now Chattanooga.[60] The next year, the Chickamauga, aligned with British loyalists, attacked Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals.[61] The warnings of Dragging Canoe's cousin Nancy Ward spared many settlers' lives from the initial attacks.[62] In spite of Dragging Canoe's protests, the Cherokee were continuously induced to sign away most of the tribe's lands to the U.S. government.

During the American Revolution, the Wataugans supplied 240 militiamen (led by John Sevier) to the frontier force known as the Overmountain Men, which defeated British loyalists at the Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780.[63] Tennessee's first attempt at statehood was the State of Franklin, formed in 1784 from three Washington District counties.[64] Its capital was initially at Jonesborough and later Greeneville, and eventually grew to include eight counties. After several unsuccessful attempts at statehood, the State of Franklin rejoined North Carolina in 1788.[65] North Carolina ceded the region to the federal government, which was designated as the Southwest Territory on May 26, 1790.[66] William Blount was appointed as the territorial governor by President George Washington, and Blount and James White established the city of Knoxville as the territory's capital in 1791.[67] The Southwest Territory recorded a population of 35,691 in the first United States census that year, about three-fourths of whom resided in what is now East Tennessee.[68]

In addition to the English and Scotch-Irish settlers, there were also a number of Welsh families who settled in East Tennessee in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These were large immigrant family groups who came from the Welsh towns of Llandeilo, Blaengweche, Llandyfan, Derwydd, Glanaman, Garnant, Upper Brynamman, Lower Brynamman, Rhosamman, Cwmllynfell, Tairgwaith, Gwain-Cae-Gurwen, Gwnfe, Twnllanan, Llanddeusant, Ystradfellte, Llandovery, Laugharne.[69]

A larger group of settlers, entirely of English descent, arrived from Virginia's Middle Peninsula. These came from the Virginia counties of Essex, Gloucester, King and Queen, King William, Mathews, and Middlesex, as well as two smaller groups from Buckingham and New Kent counties in Virginia. They arrived as a result of large landowners buying up land and expanding in such a way that smaller landholders had to leave the area in order to prosper. This massive wave essentially transplanted the population of English-descended small-holders from Virginia's Middle Peninsula to East Tennessee.[70][71]

Antebellum period[编辑]

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a series of land cessions were negotiated with the Cherokees as settlers pushed south of the Washington District.[72] The 1791 Treaty of Holston, negotiated by William Blount, established terms of relations between the United States and the Cherokees. The First Treaty of Tellico established the boundaries of the Treaty of Holston, and a series of treaties over the next two decades ceded small amounts of Cherokee lands to the U.S. government. In the Calhoun Treaty of 1819, the U.S. government purchased Cherokee lands between the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers. In anticipation of forced removal of the Cherokees, white settlers began moving into Cherokee lands in southeast Tennessee in the 1820s and 1830s.

East Tennessee was home to one of the nation's first abolitionist movements, which arose in the early 19th century. Quakers, who had migrated to the region from Pennsylvania in the 1790s, formed the Manumission Society of Tennessee in 1814. Notable supporters included Presbyterian clergyman Samuel Doak, Tusculum College cofounder Hezekiah Balch, and Maryville College president Isaac Anderson. In 1820, Elihu Embree established The Emancipator— the nation's first exclusively abolitionist newspaper— in Jonesborough.[73] After Embree's death, Benjamin Lundy established the Genius of Universal Emancipation in Greeneville in 1821 to continue Embree's work. By the 1830s, however, the region's abolitionist movement had declined in the face of fierce opposition.[74] The geography of East Tennessee, unlike parts of Middle and West Tennessee, did not allow for large plantation complexes, and as a result, slavery remained relatively uncommon in the region.[75]

In the 1820s, the Cherokees established a government modeled on the U.S. Constitution, and located their capitol at New Echota in northern Georgia.[76] In response to restrictive laws passed by the Georgia legislature, the Cherokees in 1832 moved their capital to the Red Clay Council Grounds in what is now Bradley County, a short distance north of the border with Georgia.[76] A total of eleven general councils were held at the site between 1832 and 1838, during which the Cherokees rejected multiple compromises to surrender their lands east of the Mississippi River and move west.[77] The 1835 Treaty of New Echota which was not approved by the National Council at Red Clay, stipulated that the Cherokee relocate to Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma, and provided a grace period until May 1838 for them to voluntarily migrate. In 1838 and 1839, U.S. troops forcibly removed nearly 17,000 Cherokees and about 2,000 Black people the Cherokees enslaved from their homes in southeastern Tennessee to Indian Territory. An estimated 4,000 died along the way.[78] The operation was orchestrated from Fort Cass in Charleston, which was constructed on the site of the Indian agency.[79] In the Cherokee language, the event is called Nunna daul Isunyi, meaning "the Trail Where We Cried", and it is commonly known as the Trail of Tears.[78]

The arrival of the railroad in the 1850s brought immediate economic benefits to East Tennessee, primarily to Chattanooga, which had been founded in 1839. Chattanooga quickly developed into a nexus between the mountain communities of Southern Appalachia and the cotton states of the Deep South, being referred to as the Gateway to the Deep South. In 1843, copper was discovered in the Copper Basin in the extreme southeast corner of the state, and by the 1850s, large industrial-scale mining operations were taking place, making the Copper Basin one of the most productive copper mining districts in the nation.[80]

Civil War[编辑]

The American Civil War sentiments of East Tennesseans were among the most complex of any region in the nation. Due to the rarity of slavery in the region, many East Tennesseans were suspicious of the aristocratic Southern planter class that dominated the Southern Democratic Party and most Southern state legislatures. For this reason, Whig support ran high in East Tennessee in the years leading up to the war, especially in Knox and surrounding counties. In 1860, slaves composed about 9% of East Tennessee's population, compared to 25% statewide.[81] When Tennessee voted on a referendum calling for secession in February 1861, which failed, more than 80% of East Tennesseans voted against it, including majorities in every county except Sullivan and Meigs. In June 1861, nearly 70% of East Tennesseans voted against the state's second ordinance of secession which succeeded statewide. Along with Sullivan and Meigs, however, there were pro-secession majorities in Monroe, Rhea, Sequatchie, and Polk counties.[82] There were also pro-secession majorities within the cities of Knoxville and Chattanooga, although these cities' respective counties voted decisively against secession.[83][84]

In June 1861, the Unionist East Tennessee Convention met in Greeneville, where it drafted a petition to the Tennessee General Assembly demanding that East Tennessee be allowed to form a separate Union-aligned state split off from the rest of Tennessee, similar to West Virginia.[82] The legislature rejected the petition, however, and Tennessee Governor Isham Harris ordered Confederate troops to occupy East Tennessee.[85] In the fall of 1861, Unionist guerrillas burned bridges and attacked Confederate sympathizers throughout the region, leading the Confederacy to invoke martial law in parts of East Tennessee.[86] Senator Andrew Johnson and Congressman Horace Maynard— who in, spite of being from a Confederate state, retained their seats in Congress— continuously pressed President Abraham Lincoln to send troops into East Tennessee, and Lincoln subsequently made the liberation of East Tennessee a top priority. Knoxville Whig editor William "Parson" Brownlow, who had been one of slavery's most outspoken defenders, attacked secessionism with equal fervor, and embarked on a speaking tour of the Northern states to rally support for East Tennessee.[87] In 1862, Lincoln appointed Johnson, a War Democrat, as military governor of Tennessee.[88]

A number of crucial campaigns took place in East Tennessee, although the region did not see any large-scale fighting until the second half of the war, unlike the rest of the state.[89] After being defeated at the Battle of Chickamauga in northwest Georgia in September 1863, Union troops of the Army of the Cumberland under the command of William Rosecrans fled to Chattanooga.[90] Confederate troops under Braxton Bragg attempted to besiege the Union troops into surrendering, but two months later, reinforcements from the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, Joseph Hooker, and George Henry Thomas arrived.[91] Under the command of Hooker, the Union troops defeated the Confederates at the Battle of Lookout Mountain on November 24, and the following day Grant and Thomas completely ran the Confederates out of the city at the Battle of Missionary Ridge.[92] These battles came to be known as the Chattanooga Campaign, and marked a major turning point in the war, allowing Sherman to launch the Atlanta campaign from the city in the Spring of 1864.[93] A few days after the Chattanooga Campaign concluded, Confederate General James Longstreet launched the Knoxville campaign in an effort to take control of the city. The campaign ended in defeat at the Battle of Fort Sanders on November 29, which was under the command of Union General Ambrose Burnside,[94] although Longstreet defeated Union troops under the command of James M. Shackelford at the Battle of Bean's Station two weeks later.[95] By the beginning of 1864, East Tennessee was largely under the control of the Union Army, although, despite its Unionist leanings, was the last part of the state to fall to the Union.

Reconstruction and the Progressive Era[编辑]

After the Civil War, Northern capitalists began investing heavily in East Tennessee, which helped the region's ravaged economy recover much faster than most of the South. Most new industry in Tennessee was constructed in East Tennessee during this time, and Chattanooga became one of the first industrialized cities in the South.[96] Knoxville also experienced a modest manufacturing boom, and new factories were constructed in other small towns such as Kingsport, Johnson City, Cleveland, Morristown, and Maryville, making them amongst the first Southern cities to experience the results of the industrial revolution in the United States.[96] Other cities in the region, such as Lenoir City, Harriman, Rockwood, Dayton, and Englewood, were founded as company towns during this period. The Burra Burra Mine— established in the 1890s in the Copper Basin— was at its height one of the nation's copper mining operations.[97] In 1899, the world's first Coca-Cola bottling plant was built in Chattanooga.[83] In the early 1900s, railroad and sawmill innovations allowed logging firms such as the Little River Lumber Company and Babock Lumber to harvest the virgin forests of the Great Smokies and adjacent ranges. Coal mining operations were established in coal-rich areas of the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains, namely in Scott County, northern Campbell County, and western Anderson County. In the early 1890s, Tennessee's controversial convict lease system sparked a miners' uprising in Anderson County that became known as the Coal Creek War. While the uprising was eventually crushed, it induced the state to do away with convict leasing, making Tennessee the first southern state to end the controversial practice.[98][99]

Other ambitious ventures during the period included the construction of Ocoee Dam No. 1 and Hales Bar Dam (completed in 1911 and 1913 respectively) by the forerunners of the Tennessee Electric Power Company (TEPCO).[100] In the 1920s, Tennessee Eastman— destined to become the state's largest employer— was established in Kingsport, and in nearby Elizabethton the German-owned Bemberg Corporation built two large rayon mills.[101] Equally ambitious was the Aluminum Company of America's establishment of a massive aluminum smelting operation at what is now Alcoa in 1914, which required the construction of a large plant and company town and the building of a series of dams along the Little Tennessee River to supply the plant with hydroelectric power.[102]

In the late 1800s to the early 1900s, leisure resorts oriented on mineral springs flourished in the region,[103] with the most popular being Tate Springs in Grainger County, which attracted many prestigious families of the era, including the Ford, Rockefeller, Firestone, Studebaker, and Mellon families.[104]

The region received international attention in the public execution of a circus elephant via hanging. After killing its trainer in a circus performance in Kingsport, the elephant would be transported to Erwin in nearby Unicoi County, and hung in front of a crowd of roughly 2,500 residents. A picture of the undertaking would be widely distributed by American pulp magazine Argosy.[105]

In the 1920s, East Tennessee surpassed Middle Tennessee as the state's most populous Grand Division, primarily as a result of the larger African American population in that region fleeing to Northern industrial cities as part of the Great Migration.[81]

The Great Depression, TVA, and World War II[编辑]

Over a period of two decades, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), created in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression, drastically altered the economic, cultural, and physical landscape of East Tennessee. TVA sought to build a series of dams across the Tennessee River watershed to control flooding, bring cheap electricity to East Tennessee, and connect Knoxville and Chattanooga to the nation's inland waterways by creating a continuously navigable channel along the entirety of the Tennessee River. Starting with Norris Dam in 1933, the agency built 10 dams in East Tennessee (and five more across the border in North Carolina and Georgia) over a period of two decades. Melton Hill and Nickajack were added in the 1960s, and the last, Tellico Dam, was completed in 1979 after a contentious five-year legal battle with environmentalists.[106] TVA also gained control of TEPCO's assets after a legal struggle in the 1930s with TEPCO president Jo Conn Guild and attorney Wendell Willkie that was eventually dismissed by the U.S. Supreme Court.[107]

The TVA's construction of hydroelectric dams in the East Tennessee region would receive criticism with for what some have perceived as excessive use of its authority of eminent domain and an unwillingness to compromise with landowners. All of TVA's hydroelectric projects in East Tennessee were made possible through the use of eminent domain,[108][109] and required the removal of 125,000 Tennessee Valley residents.[110] Residents who refused to sell to the TVA were often forced by court orders and lawsuits.[108] In the region, several projects inundated historic Native American sites and American Revolution-era towns.[111][112] On some occasions, land that TVA had acquired through eminent domain that was expected to be inundated was not, and was sold to private developers for the construction of planned communities such as Tellico Village in Loudon County.[113]

East Tennessee's physiographic layout and rural nature made it the ideal location for the uranium enrichment facilities of the Manhattan Project— the federal government's top secret World War II-era initiative to build the first atomic bomb. Starting in 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built what is now the city of Oak Ridge, and the following year work began on the enrichment facilities, K-25 and Y-12.[114] During the same period, Tennessee Eastman built the Holston Ordnance Works in Kingsport for the manufacture of an explosive known as Composition B,[115] and the Department of Defense constructed the Volunteer Ordnance Works in Chattanooga to produce TNT.[116] The ALCOA corporation, seeking to meet the wartime demand for aluminum (which was needed for aircraft construction), built its North Plant, which at the time of its completion was the world's largest plant under a single roof.[117] To meet the region's skyrocketing demand for electricity, TVA hastened its dam construction, completing Cherokee and Douglas dams in record time, and building the massive Fontana Dam just across the state line in North Carolina.[118]

Mid-20th century to present[编辑]

In 1955, Oak Ridge High School became the first public school in Tennessee to be integrated. This occurred one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation to be unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. In 1956, judge Robert Love Taylor ordered nearby Clinton High School to be integrated, and a crisis developed when pro-segregationists threatened violence, prompting then-governor Frank G. Clement to send in Tennessee National Guard troops to assist with the integration process.[119]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, federal investments into urbanized areas provided major cities of the East Tennessee region to establish urban renewal initiatives, often involving the demolition or redevelopment of blighted commercial areas or neighborhoods for new public buildings and freeways. These projects would often involve the controversial removal and redlining of poverty-stricken and minority households.[120][121]

In 1965, Congress created the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) to improve economic development and job opportunities in the Appalachian region. The program resulted in the construction of new and improved highways in East Tennessee through the Appalachian Development Highway System (ADHS), and brought new industries to rural, impoverished counties in the region that had previously been dependent on declining sectors such as coal mining and logging. With the investment of the ARC, several cities emerged as industrial hubs of the East Tennessee region, including Cleveland, Kingsport, Knoxville, and Morristown.[122] Beginning around this time, East Tennessee, along with the rest of the state, began to benefit from the nationwide Sun Belt phenomenon, which brought additional economic growth to the region.[123] The region saw its most rapid growth in the 1970s. Chattanooga, however, began to decline in the 1960s, and was declared by the Federal government to be the most polluted city in the country in 1969.[124] In the mid-1980s, the city leaders launched a program called "Vision 2000", which worked to revitalize and reinvent the city's economy, and eventually resulted in a reversal of Chattanooga's decline.[125]

TVA's construction of the Tellico Dam in Loudon County became the subject of national controversy in the 1970s when the endangered snail darter fish was reported to be affected by the project.[126] After lawsuits by environmental groups, the debate was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court case Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill in 1978, leading to amendments of the Endangered Species Act.[127]

In 1982, a World's Fair was held in Knoxville.[128] The fair was also known as the "Knoxville International Energy Exposition", and its theme was "Energy Turns the World." The fair was one of the most successful, attracting more than eleven million visitors during its six-month run, and is the most recent world's fair to have been held in the United States.[129] In 1996, the whitewater slalom events of the Atlanta Summer Olympic Games were held on the Ocoee River in Polk County. These are the only Olympic sporting events to have ever been held in Tennessee.[130]

A number of high profile disasters have occurred in East Tennessee since the latter 20th century. On May 13, 1972, the deadliest motor vehicle accident in state history occurred near Bean Station on U.S. Route 11W when a tractor-trailer and a Greyhound bus collided head-on, killing 14 and injuring 15.[131] The accident would prompt the rapid construction of additional four-lane arterial highways in the East Tennessee region throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, as well as place a focus on the completion of Interstates 40, 75, and 81, which occurred in the mid-1970s.[132] On December 11, 1990, a 99-vehicle collision occurred in dense fog on Interstate 75 near Calhoun, killing 12 and injuring 42, and was reportedly the largest motor vehicle accident in U.S. history at the time, in terms of the number of vehicles.[133][134] On December 23, 2008, the largest industrial waste spill in United States history occurred at TVA's Kingston Fossil Plant when a dike failed, releasing more than 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash slurry into the Emory and Clinch Rivers.[135][136] The cleanup cost TVA more than $1 billion, and was not completed until 2015.[137]

Music[编辑]

Appalachian music has evolved from a blend of English and Scottish ballads, Irish and Scottish fiddle tunes, African-American blues, and religious music. In 1916 and 1917, British folklorist Cecil Sharp visited Flag Pond, Sevierville, Harrogate, and other rural areas in the region where he transcribed dozens of examples of "Old World" ballads that had been passed down generation to generation from the region's early English settlers.[138] Uncle Am Stuart, Charlie Bowman, Clarence Ashley, G. B. Grayson, and Theron Hale were among the most successful early musicians from East Tennessee.

In 1927, the Victor Talking Machine Company conducted a series of recording sessions in Bristol that saw the rise of musicians such as Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. Subsequent recording sessions, such as the Johnson City sessions in 1928 and the Knoxville St. James Sessions in 1930 proved lucrative, but by the late 1930s, the success of the Grand Ole Opry had lured much of the region's talent to Nashville. In the 1940s, the Grand Ole Opry and associated music labels began using "country" instead of "hillbilly" for their genre, hoping to attract a wider audience.[139]

Union County would prove influential to later developments in country music with musicians Roy Acuff, Chet Atkins, and Carl Smith who were born in the county assisted with the international breakthrough of the genre, and the development of the Nashville sound and rockabilly.[140]

In popular culture[编辑]

East Tennessee culture has been represented in many hit songs, television shows and movies. The Ford Show, which ran on NBC from 1956 until 1961, was hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford (originally from Bristol).

Davy Crockett[编辑]

The Ballad of Davy Crockett helped to popularize the 1955 film Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier. First recorded and introduced on the television series Disneyland in 1954, it has been covered by a number of artists, most notably Tennessee Ernie Ford. The song's lyrics say Crockett was "born on a mountaintop in Tennessee", but his actual birthplace was in Limestone, Tennessee, the location of Davy Crockett Birthplace State Park.[141] In addition to his renowned frontier exploits and military service, Crockett served Tennessee as a state legislator and Congressman.

Daniel Boone[编辑]

The folk hero Daniel Boone, who helped explore East Tennessee, was honored in the soundtrack for the television series Daniel Boone, which ran from 1964 until 1970.[142][143][144] The last of three versions of the theme song was sung by The Imperials, a Grammy-winning Christian music group.[145][146]

Christy[编辑]

Christy, a 1990s CBS television series, was based on village life in 1910s East Tennessee.[147] The show, which was later developed into a television movie series, featured traditional mountain music.[148][149] "ChristyFest", held each summer, is dedicated to the novel, musical,[150] TV series, and movies, and includes live folk music.[151][152]

Dolly Parton's Coat of Many Colors[编辑]

The television film Dolly Parton's Coat of Many Colors aired on NBC in 2015. The film was inspired by her 1971 song and album of the same name, and recounts her childhood in the mountains of East Tennessee. The film was generally praised by critics, and received the Tex Ritter Award from the Academy of Country Music.[153]

Economy[编辑]

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, East Tennessee's economy relied heavily on subsistence agriculture. Agriculture still plays a vital role in Tennessee's economy, such as Grainger County's renowned tomatoes. In the cities, however, manufacturing was the main source of prosperity and growth. In the years following the Civil War, Chattanooga became one of the first industrial cities in the South. Other cities in East Tennessee such as Knoxville, Kingsport, Cleveland, Maryville, and Morristown were among some of the first cities in Tennessee to experience the effects of the Industrial revolution in the United States, and most manufacturing facilities constructed in the state in the latter 19th century located in East Tennessee.[96] The region's economy remained predominantly agrarian during this time, however.

Industry[编辑]

A variety of goods are manufactured in East Tennessee, including chemicals, foods and drinks, automotive components, and electronics. The largest manufacturer in the region is Eastman Chemical in Kingsport, with more than 10,000 employees, and other chemical companies operate several other chemical manufacturing facilities in the region. Volkswagen operates an assembly plant in Chattanooga, and several automotive parts manufacturers, including Denso, operate plants in East Tennessee. Coca-Cola was first produced in Chattanooga in 1899, and a number of well-known food and drink brands originated and are made in East Tennessee, including Mayfield Dairy products, Moon Pie, Little Debbie, Mountain Dew, Bush's Beans, and M&M's. The region has also emerged in recent years as one of the top locations for the legal production of moonshine.[154] East Tennessee is also a top location where boats are manufactured, with companies such as Sea Ray, MasterCraft, and Malibu Boats, operating facilities in the region.[155] Other important products produced in East Tennessee include consumer electronics, electrical equipment, and fabricated metal products.

Business[编辑]

Major companies and businesses headquartered in East Tennessee include Pilot Flying J, the Baptist Hospital system, Regal Cinemas in Knoxville, and BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, U.S. Xpress, Covenant Transport, and Unum in Chattanooga.

Science and technology[编辑]

The Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and Y-12 National Security Complex in Oak Ridge are two of the largest employers in East Tennessee. ORNL conducts scientific research in materials science, nuclear physics, energy, high-performance computing, systems biology, and national security,[156] and is also the largest national laboratory in the Department of Energy (DOE) system by size, and has the third highest budget.[157] Both ORNL and Y-12 also support many jobs through contracting firms in the area. Since the 1990s, the geographical area between Oak Ridge and Knoxville has been known as the Tennessee Technology Corridor, with more than 500 high-tech firms located in the region.[158] With the expanded smart grid in Chattanooga, and the fastest internet in the Western Hemisphere,[159] Chattanooga has begun to grow its technical and financial sectors due to its burgeoning start-up scene.[160]

The town of Erwin, located in the Tri-Cities area, is home to Nuclear Fuel Services, which operates a manufacturing and uranium enrichment facility converting Cold War-era weapons uranium into commercially usable reactor fuel for power plants around the United States, and is the largest supplier of uranium fuel for the United States Navy since 1960.[161][162]

Energy[编辑]

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) has its administrative operations headquartered in Knoxville and power operations headquartered in Chattanooga, and provides nearly all of East Tennessee's electricity. TVA operates the Sequoyah and Watts Bar nuclear plants in Soddy-Daisy and Rhea County, respectively, the Kingston and Bull Run coal-fired plants, the latter of which is near Oak Ridge, the John Sevier combined cycle natural gas-fired plant near Rogersville, the Raccoon Mountain Pumped-Storage Plant near Chattanooga, a wind-powered facility near Oak Ridge, and several hydroelectric dams in East Tennessee.

The two newest civilian nuclear power reactors in the United States are located at the Watts Bar Nuclear Plant. Unit 1 began operation in 1996 and Unit 2 started operating in 2016, making it the first and only new nuclear power reactor to begin operation in the United States in the 21st century.[164] Officials at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the TVA are studying advancements in nuclear power as an energy source in a joint effort, including small modular reactors.[165]

Mining[编辑]

The Ridge-and-Valley region of East Tennessee is home to several of the largest deposits of zinc in the United States, including the Mossy Creek and Clinch Valley Zinc Deposits of Jefferson and Grainger-Hancock counties respectively.[166]

Tennessee marble, a rare crystalline form of limestone, is found only in several deposits in the East Tennessee region in the entire world. Its strong resemblance to true marble when polished has made it a popular construction material found in several structures and monuments around the United States.[167] The stone occurs in belts of Ordovician-period rocks known as the Holston Formation,[167] Tennessee marble achieved such popularity in the late-19th century that Knoxville, the stone's primary finishing and distribution center, became known as "The Marble City."[168]

Tourism[编辑]

While the mountain springs of East Tennessee and the cooler upper elevations of its mountainous areas have long provided a retreat from the region's summertime heat, much of East Tennessee's tourism industry is a result of land conservation movements in the 1920s and 1930s. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, established in 1934, led to a tourism boom in Sevier and Blount counties, effectively converting the tiny mountain hamlets of Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge into resort towns. Today, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most visited national park in the United States, receiving more than 14 million visitors annually. The park also anchors a massive tourism industry in nearby Gatlinburg, Pigeon Forge, and Sevierville, which is the third largest in the state.[170] Some of these attractions Dollywood, the most visited ticketed attraction in Tennessee, Ober Gatlinburg, and Ripley's Aquarium of the Smokies.

Other tourist attractions maintained by the National Park Service (NPS) in East Tennessee are Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area and Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, both in the Cumberland Mountains, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, and the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. East Tennessee is home to several scenic roadways including the Foothills Parkway, the East Tennessee Crossing Byway, the Norris Freeway, Cumberland National Scenic Byway, the Tail of the Dragon, the Cherohala Skyway, and the Ocoee Scenic Byway.[171]

The Appalachian Trail, one of the world's most well-known hiking trails, was built in the mid-1930s and passes along the Tennessee-North Carolina border. The Cherokee National Forest was established during the same period and preserves most of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Tennessee that are not part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Ocoee River in Polk County attracts thousands of whitewater rafters each year and is the most rafted river in the nation. The nearby gentler Hiwassee River is also a top attraction in East Tennessee.[172] Reservoirs created in the aftermath of the TVA's hydroelectric projects in the upper East Tennessee region, including Cherokee, Douglas, Fort Loudoun, and Norris provide recreational opportunities on and along the shores via water sports, boating, fishing, and "second-home" development.[173]

Attractions in Chattanooga include the Tennessee Aquarium, the nation's largest freshwater aquarium, and Rock City, and Ruby Falls on Lookout Mountain, the latter two of which are perhaps best known for their unique advertisements painted on barn roofs across the southeast.[174] The Tennessee Aquarium coincided with the revitalization of Chattanooga's riverfront, which helped to bolster the downtown districts.[175] The city has become an outdoor sports mecca, being heralded as the "Best Town Ever" by Outside magazine.[176] Knoxville hosted the 1982 World's Fair, which drew over 11 million visitors, making it one of the most popular world's fairs in history.

Transportation[编辑]

Roads[编辑]

Interstate 75 (I-75) enters East Tennessee in Chattanooga, runs northeast to Knoxville, and then turns north, passing through the Cumberland Mountains into Kentucky. Interstate 40 (I-40) traverses the region in an east to west alignment, passing through Knoxville. I-40 and I-75 run concurrent for nearly 20英里(32公里) in Knoxville and carry more than 210,000 vehicles per day at their busiest point, the highest traffic volume in Tennessee. Interstate 81 (I-81) begins about 35英里(56公里) east of Knoxville, and runs northeast to Bristol. Interstate 26 (I-26), while technically an east–west route, begins in Kingsport, runs south to Johnson City, and enters North Carolina to the south, crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains. Interstate 24 (I-24) terminates in Chattanooga, and connects the region to Nashville. In Knoxville, both I-40 and I-75 each have auxiliary routes: I-140, I-640, and I-275. Several designated corridors of the Appalachian Development Highway System are located in the region, including Corridors B, F, J, K, S, and V, which provide expressway connection to Interstate Highways.[177] Other major surface routes in East Tennessee which are part of the National Highway System (NHS) are U.S. Routes 11W, 19, 25E, 27, 64, 321, and 411.[178][179]

Air, rail, and water[编辑]

Major airports in East Tennessee include McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) in Alcoa outside of Knoxville, Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport (CHA), and Tri-Cities Regional Airport (TRI) in Blountville. Several other general aviation airports are located in the region. Norfolk Southern Railway operates rail lines in East Tennessee, include multiple tracks that intersect in Knoxville and Chattanooga. The Tennessee River is the only navigable waterway in East Tennessee via a lock-and-canal system at through several TVA hydroelectric dams.[180]

Higher education[编辑]

The region's major public universities are the Knoxville and Chattanooga campuses of the University of Tennessee and East Tennessee State University in Johnson City. Private four-year institutions include Bryan College, Carson–Newman University, King University, Lee University, Lincoln Memorial University, Maryville College, Milligan College, Lipscomb University, Johnson University, Tennessee Wesleyan University, and Tusculum University. Several public community colleges and vocational/technical schools also are located in the region, such as Northeast State Community College in Blountville, Walters State Community College in Morristown, Pellissippi State Community College near Knoxville, Chattanooga State Community College, and Cleveland State Community College. The Tennessee College of Applied Technology has several campuses across the area.

The University of Tennessee's athletic teams, nicknamed the "Volunteers", or "Vols", are the region's most popular sports teams, and constitute a multimillion-dollar industry.[181] The university's football team plays at Neyland Stadium, one of the nation's largest stadiums.[182] Neyland is flanked by the Thompson–Boling Arena, which has broken several attendance records for college men's and women's basketball.[183]

Legal structure[编辑]

According to the state constitution, no more than two of the Tennessee Supreme Court's five justices can come from any one Grand Division.[184] The Supreme Court rotates meeting in courthouses in each of the three divisions. The Supreme Court building for East Tennessee is in Knoxville. A similar rule applies to certain other commissions and boards as well, to prevent them from showing a geographic and population bias.

Politics[编辑]

| Year | REP | DEM | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 68.95% 771,077 | 29.26% 327,193 | 1.79% 20,041 |

| 2016[186] | 69.26% 638,260 | 25.96% 239,241 | 4.78% 44,086 |

| 2012[187] | 68.00% 602,623 | 30.22% 267,804 | 1.78% 15,760 |

| 2008[188] | 65.28% 610,413 | 33.22% 310,586 | 1.50% 14,021 |

| 2004[189] | 63.91% 573,626 | 35.33% 317,150 | 0.76% 6,783 |

| 2000[190] | 58.34% 449,014 | 40.00% 307,924 | 1.66% 12,772 |

Politically, East Tennessee has historically been a massive outlier in Tennessee and the South. It is one of the few regions in the South that have consistently voted Republican since the Civil War, and one of the oldest Republican regions in the United States. Indeed, several counties in the region are among the few in the country to have never voted for a Democrat in a presidential election.

The state's 1st and 2nd congressional districts, anchored in the Tri-Cities and Knoxville respectively, are among the few ancestrally Republican regions in the South. The 1st has been held by Republicans or their predecessors without interruption since 1881, and for all but four years since 1859.[191] The 2nd has been in the hands of Republicans or their predecessors since 1855.[192] Until the 1950s, congressmen from the 1st and 2nd Districts were among the few truly senior Republican congressmen from the South. Historically, Democrats were more competitive in the Chattanooga-based 3rd district, but recent trends have made it almost as staunchly Republican as the 1st and 2nd districts.

East Tennessee Republican leanings are rooted in its antebellum Whig sentiments (historian O.P. Temple actually traces this sentiment back to the anti-aristocratic Covenanters of Scotland).[193] As in much of Southern Appalachia, the region's yeoman farmers clashed with the large-scale planters and business interests that controlled the Democratic Party and dominated most southern state legislatures. East Tennesseans revered the likes of John Sevier and Davy Crockett, and were drawn to the political philosophies of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.[193] They tended to reject the policies of the Southern Democrats, who were deemed "aristocratic" (Andrew Jackson's popularity in the Chattanooga area— which he helped open to European-American settlement— created a stronger Democratic base in southeastern Tennessee, however). In the early 1840s, then-state senator Andrew Johnson actually introduced a bill in the state legislature that would have created a separate state in East Tennessee.[194]

While the Whigs disintegrated in the 1850s, East Tennesseans continued their opposition to Southern Democrats with the Opposition Party and the Constitutional Union Party, the latter capturing the state's electoral votes in 1860. Pro-Union sentiment during the Civil War (which was reinforced by the Confederate army's occupation of the region) evolved into support for President Lincoln. The congressmen from the 1st and 2nd districts were the only congressmen who did not resign when Tennessee seceded. The residents of those districts immediately identified with the Republicans after hostilities ceased and have supported the GOP, through good times and bad, ever since.

The Radical Republican post-war policies of Governor William "Parson" Brownlow greatly polarized the state along party lines, with East Tennesseans mostly supporting Brownlow and Middle and West Tennesseans mostly rejecting him. The Southern Democrats regained control of the state government in the early 1870s, but Republican sentiment remained solid in East Tennessee, especially in the 1st and 2nd Districts. By the 1880s, the state's Democrats had an unwritten agreement with the state's Republicans whereby Republicans would split presidential patronage of Republican presidencies with the Democrats so long as the Democrats allowed them continued influence in state affairs.[195]

In 1888, Pennsylvania-born Henry Clay Evans was elected to the congressional seat for the 3rd District (the Chattanooga area). Evans, who rejected compromise and the splitting of presidential patronage with the state's Democrats, strongly supported a bill that would have turned over control of state elections to the federal government. In response, the state legislature gerrymandered the 3rd District, ensuring Evans' defeat in 1890.[195] After 1901, more than a half-century passed without the state legislature redistricting, in spite of population shifts. In 1959, Memphis resident Charles Baker sued the legislature in hopes of forcing it to redraw the districts, culminating in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Baker v. Carr.[196] In the decades after this case, the 3rd District has been redrawn several times, and a new 4th District was carved in part out of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Districts. The 2000s round of redistricting made the 3rd more Republican and the 4th more Democratic.[197] After the 2010 elections and the redistricting before 2012, though, the Republicans in control of state government made both the 3rd and 4th Districts significantly more Republican, and both are now on paper among the most Republican districts in the country.

Notes[编辑]

- ^ Three counties— Bledsoe, Sequatchie, and Marion— are located in the Sequatchie Valley. These counties were traditionally part of East Tennessee. However, Sequatchie and Marion counties were reassigned to the Middle Tennessee grand division circa 1932. Marion County was later returned to East Tennessee, but Sequatchie County legally remains part of Middle Tennessee.[1][15]

References[编辑]

Citations[编辑]

- ^ 1.0 1.1 Tennessee Blue Book 2015-2016 (PDF). sos.tn.gov. Nashville: Tennessee Secretary of State: 639. 2015 [June 5, 2021].

- ^ Siner, Emily. How The U.S. Created A 'Secret City' In Oak Ridge To Build The Atomic Bomb, 75 Years Ago. WPLN-FM (Nashville). September 20, 2017 [June 5, 2021].

- ^ Abramson, Rudy; Gowen, Troy; Haskell, Jean; Oxendine, Jill. Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. 2006: xix–xxv [July 23, 2021]. ISBN 9781572334564 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Ted Olson and Ajay Kalra, "Appalachian Music: Examining Popular Assumptions". A Handbook to Appalachia: An Introduction to the Region (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 163-170.

- ^ Grand Divisions. tennesseehistory.org. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society. November 14, 2020 [July 17, 2021].

- ^ Hudson, John C. Across this Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. JHU Press. 2002: 101–116. ISBN 978-0-8018-6567-1 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Moore 1994,第68–72頁.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Moore 1994,第57-58, 64, 68頁.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 USGS GNIS - Unicoi Mountains, USGS GNIS - Bald Mountains, USGS GNIS - Unaka Mountains, USGS GNIS - Great Smoky Mountains.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Federal Lands and Indian Reservations - Tennessee (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior. 2003 [June 20, 2021] –通过University of Texas Libraries.

- ^ Appalachian Trail Map (PDF). nps.gov. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. [July 17, 2021].

- ^ Tennessee topographic map, elevation, relief. topographic-map.com. [January 22, 2022].

- ^ Maertens, Thomas Brock. The Relationship of Maintenance Costs to Terrain and Climate on Interstate 40 in Tennessee (PDF) (学位论文). The University of Tennessee. June 10, 1980 [2021-06-27]. Docket ADA085221.

- ^ Geology and History of the Cumberland Plateau (PDF). nps.gov. National Park Service. [May 27, 2021].

- ^ Tennessee's Counties (PDF). state.tn.us. Nashville: Tennessee Secretary of State: 507. 2005 [June 5, 2021]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于March 2, 2006).

- ^ Cumberland Trail State Scenic Trail - 2020. arcgis. Cumberland Trails Conference. 2020 [July 17, 2021].

- ^ Tennessee Vacations - Tennessee Dept. of Tourism. Tennessee Vacation.

- ^ World Map of Köppen−Geiger Climate Classification (PDF). [December 19, 2008]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于January 14, 2009).

- ^ A look at Tennessee Agriculture (PDF). Agclassroom.org. [November 1, 2006]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于June 14, 2016).

- ^ Wiltgen, Nick. The Snowiest Places in Each State. The Weather Channel. October 27, 2016 [July 2, 2019]. (原始内容存档于June 4, 2019).

- ^ Nashville Weather Records (1871-Present). weather.gov. Nashville: National Weather Service. [May 27, 2021].

- ^ Speaks, Dewaine A. Historic Disasters of East Tennessee. Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. August 5, 2019: 17–23. ISBN 9781467141895 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Historical Population Change Data (1910–2020). Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. [May 1, 2021]. (原始内容存档于April 29, 2021).

- ^ U.S. Census website. United States Census Bureau. 2010 [2019-12-29].

- ^ Chokshi, Niraj. Diversity in America's counties, in 5 maps. The Washington Post (Washington, D.C.). June 30, 2014 [2019-10-26].

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 U.S. Census website. United States Census Bureau. [2019-09-19].

- ^ OMB Bulletin No. 18-04: Revised Delineations of Metropolitan Statistical Areas, Micropolitan Statistical Areas, and Combined Statistical Areas, and Guidance on Uses of the Delineations of These Areas (PDF). United States Office of Management and Budget. September 14, 2018 [June 29, 2019].

- ^ 28.0 28.1 28.2 City and Town Population Totals: 2010-2019. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. [May 21, 2020].

- ^ 29.0 29.1 Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010–2019. U.S. Census Bureau. June 18, 2020 [June 29, 2020].

- ^ Staff. East Tennessee cities ranks in top 5 for longest commute times. WATE-TV. December 13, 2017 [4 January 2022].

- ^ 31.0 31.1 Chapman, Jefferson. Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History. Publications in Anthropology (Knoxville: University of Tennessee). 1985, 41 (1).

- ^ Moccasin Bend Archeological District. National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. [July 1, 2008]. (原始内容存档于March 10, 2009).

- ^ Satz 1979,第8-11頁.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Hudson, Charles M. The Juan Pardo Expeditions: Explorations of the Carolinas and Tennessee, 1566–1568. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. 2005: 10–13, 36–40, 104. ISBN 9780817351908 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第16-17頁.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Satz 1979,第8–11頁.

- ^ Satz 1979,第34–35頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第25–26頁.

- ^ Langsdon 2000,第4–5頁.

- ^ Hudson, Charles M.; Smith, Marvin T.; DePratter, Chester B.; Kelley, Emilia. The Tristán de Luna Expedition, 1559-1561. Southeastern Archaeology (Taylor & Francis). 1989, 8 (1): 31–45. JSTOR 40712896.

- ^ Finger 2001,第20–21頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第27–28頁.

- ^ Finger 2001,第40–42頁.

- ^ Finger 2001,第35頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第32–33頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第33頁.

- ^ Finger 2001,第36–37頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第36頁.

- ^ Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 Revised Expanded. New York: Oxford University Press. 2007: 58–60. ISBN 978-0-1951-6247-9.

- ^ Langsdon 2000,第8頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第43–44頁.

- ^ Coffey, Ken. The First Family of Tennessee. Grainger County Historic Society. Thomas Daugherty. October 19, 2012 [August 20, 2020]. (原始内容存档于August 11, 2020).

- ^ Brown, Fred. Marking Time (Paperback). Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. 2005: 99–101 [October 17, 2020]. ISBN 9781572333307 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Finger 2001,第45–47頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第106頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第60–61頁.

- ^ Finger 2001,第64–68頁.

- ^ Henderson, Archibald. The Conquest of the Old Southwest: The Romantic Story of the Early Pioneers Into Virginia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Kentucky, 1740-1790. New York City: The Century Company. 1920: 212–236 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第197頁.

- ^ Satz 1979,第66頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第65–67頁.

- ^ King, Duane H. (编). The Memoirs of Lt. Henry Timberlake : The Story of a Soldier, Adventurer, and Emissary to the Cherokees, 1756-1765. Cherokee, North Carolina: Museum of the Cherokee Indian Press. 2007: 122 [March 28, 2015]. ISBN 9780807831267 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Finger 2001,第84–88頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第73–74頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第81–83頁.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第86–87頁.

- ^ Langsdon 2000,第16–17頁.

- ^ Lamon 1980,第4頁.

- ^ The Welsh of Tennessee by Y Lolfa, 2012. Pg. 19 - ISBN 9781847714299

- ^ Tennessee History: The Land, The People And the Culture. University of Tennessee Press, 1998. Pg. 19, 33-34 - ISBN 9781572330009

- ^ First Families of Tennessee: A Register of Early Settlers and Their Present-day Descendants by The East Tennessee Historical Society, 2000 pg. 77

- ^ Treaties and Land Cessions Involving the Cherokee Nation (PDF). Vanderbilt University. April 12, 2016 [May 20, 2021].

- ^ Lamon, Lester C. Blacks in Tennessee, 1791–1970

. University of Tennessee Press. 1980: 7–9. ISBN 978-0-87049-324-9 –通过Internet Archive.

. University of Tennessee Press. 1980: 7–9. ISBN 978-0-87049-324-9 –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ Goodheart, Lawrence B. Tennessee's Antislavery Movement Reconsidered: The Example of Elihu Embree. Tennessee Historical Quarterly (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society). Fall 1982, 41 (3): 224–238. JSTOR 42626297.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第210頁.

- ^ 76.0 76.1 Corn, James F. Red Clay and Rattlesnake Springs: A History of the Cherokee Indians of Bradley County, Tennessee. Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth Publishing Company. 1959: 67–70.

- ^ Lillard, Roy G. Bradley County. Memphis State University Press. 1980. ISBN 0-87870-099-4. OCLC 6934932 –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ 78.0 78.1 Satz 1979,第103頁.

- ^ Fort Cass (PDF). mtsuhistpress.org. Murfreesboro, Tennessee: Middle Tennessee State University. 2013 [2020-11-07].

- ^ Waters, Jack. Mining the Copper Basin in Southeast Tennessee. The Tellico Plains Mountain Press (Tellico Plains, Tennessee). [2008-05-30].

- ^ 81.0 81.1 Lamon (1980), p. 116

- ^ 82.0 82.1 Eric Lacy, Vanquished Volunteers: East Tennessee Sectionalism from Statehood to Secession (Johnson City, Tenn.: East Tennessee State University Press, 1965), pp. 122-126, 217-233.

- ^ 83.0 83.1 Timothy Ezzell, Chattanooga. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ William MacArthur, Jr., Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South (Tulsa, Oklahoma: Continental Heritage Press, 1982), 42-44.

- ^ Temple 1899,第340-365頁.

- ^ Madden, David. Unionist Resistance to Confederate Occupation: The Bridge Burners of East Tennessee. East Tennessee Historical Society Publications. 1980, 52: 42–53.

- ^ Corlew 1981,第34-35, 69-74頁.

- ^ Langsdon 2000,第131頁.

- ^ CWSAC Report. Civil War Sites Advisory Commission. National Park Service. 8 December 1997 [17 February 2020]. (原始内容存档于19 December 2018).

- ^ Temple 1899,第468-469頁.

- ^ Connelly, Thomas Lawrence. Civil War Tennessee: Battles and Leaders. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. 1979: 77–79. ISBN 9780870492617 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Connelly (1979), pp. 80-82

- ^ Atlanta Campaign. Civil War On the Western Border. Jefferson City, Missouri: Missouri State Library. [2021-07-27].

- ^ Temple 1899,第491-493頁.

- ^ Hess, Earl J. The Knoxville Campaign: Burnside and Longstreet in East Tennessee. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. November 15, 2012: 207–220 [May 11, 2021]. ISBN 978-1-57233-924-8 –通过Google Books.

- ^ 96.0 96.1 96.2 Belissary, Constantine G. The Rise of Industry and the Industrial Spirit in Tennessee, 1865-1885. The Journal of Southern History. May 1953, 19 (2): 193–215. JSTOR 2955013. doi:10.2307/2955013.

- ^ Cochran, Kim. Minerals and Mining of the Copper Basin. gamineral.org. Georgia Mineral Society. [May 30, 2008].

- ^ Cotham, Perry C. Toil, Turmoil & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin, Tennessee: Hillsboro Press. 1995: 56–80 [May 23, 2021]. ISBN 9781881576648 –通过Google Books.

- ^ Shapiro, Karin. A New South Rebellion: The Battle Against Convict Labor in the Tennessee Coalfields, 1871-1896. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. 1998: 75–102, 184–205 [May 23, 2021]. ISBN 9780807867051 –通过Google Books.

- ^ James Jones, Jr., TEPCO. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ James Fickle, Industry. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ Russell Parker, "Alcoa, Tennessee: The Early Years, 1919–1939." East Tennessee Historical Society Publications Vol. 48 (1976), pp. 84-100.

- ^ Sun, P.C.P; Criner, J.H.; Poole, J.L. Large Springs of East Tennessee (PDF). United States Geological Survey. 1963 [October 7, 2021].

- ^ Spring Histories. Tennessee State Library. [December 21, 2020].

- ^ Brummette, John. Trains, Chains, Blame, and Elephant Appeal: A Case Study of the Public Relations Significance of Mary the Elephant. Public Relations Review. 2012, 38 (3): 341–346. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2011.11.013.

- ^ Bruce Wheeler, Tennessee Valley Authority. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ Timothy Ezzell, Jo Conn Guild. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ 108.0 108.1 Onion, Rebecca. The Tennessee Valley Authority vs. the Family That Just Wouldn't Leave. Slate Magazine. September 5, 2013 [March 4, 2019].

- ^ TVA. Tennessee Historical Society. March 13, 2017 [July 5, 2021]. (原始内容存档于July 9, 2021).

- ^ John Gaventa. Book Review, 'TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam Area'. Tennessee Law Review. Symposium, the Tennessee Valley Authority (Knoxville, Tennessee: Tennessee Law Review Association). 1982: 979–983.

Over the past fifty years the agency has had many opportunities to learn from its mistakes. Since 1933, over 125,000 residents have been displaced from their homesteads by TVA dam construction projects.

- ^ Jefferson Chapman, Tellico Archaeology: 12,000 Years of Native American History (Tennessee Valley Authority, 1985).

- ^ Vicki Rozema, Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation (Winston-Salem: John F. Blair), 135.

- ^ Madden, Tom. Private land TVA claimed for lake to be given away to developers. UPI (Boca Raton, Florida). July 2, 1981 [March 4, 2019].

- ^ Siner, Emily. How The U.S. Created A 'Secret City' In Oak Ridge To Build The Atomic Bomb, 75 Years Ago. WPLN-FM (Nashville). September 20, 2017 [June 5, 2021].

- ^ Patricia Brake, World War II. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009.

- ^ Martin, John. 3 In Your Town: The Bunkers at Enterprise South Nature Park. WRCB-TV (Chattanooga). May 4, 2020 [October 7, 2021].

- ^ Russell Parker, "Alcoa, Tennessee: The Years of Change, 1940–1960." East Tennessee Historical Society Publications Vol. 49 (1977), pp. 99-117.

- ^ Tennessee Valley Authority, The Douglas Project: A Comprehensive Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, and Initial Operations of the Douglas Project, Technical Report No. 10 (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949), 1-12, 28.

- ^ Lamon (1980), pp. 100–101

- ^ Duncan, Heather. Losing Home: When Urban Renewal Came to Knoxville. WUOT-FM. University of Tennessee. May 13, 2021 [5 January 2022].

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik; Robertson, Noah. How Chattanooga is working to right the wrongs of urban renewal. The Christian Science Monitor. September 28, 2021 [5 January 2022].

- ^ Newman, Anne. Kendrick, Elise , 编. The Recruiters and the Recruited: How One Town Filled an Industrial Park. Appalachia (University of California, Berkeley: Appalachian Regional Commission). 1981, 15 (1): 6–19 [September 14, 2020] (英语).

- ^ Schulman, Bruce J. Review: The Sunbelt South: Old Times Forgotten. Reviews in American History (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press). June 1993, 21 (2): 340–345. JSTOR 2703223. doi:10.2307/2703223.

- ^ Micheli, Robin. Rebooting Chattanooga's fortunes. CNBC. November 18, 2013 [October 4, 2021].

- ^ Wotapka, Dawn. Chattanooga Reinvents Itself, at Its Own Pace. The Wall Street Journal (New York City). April 17, 2012 [October 7, 2021].

- ^ Telling the Story of Tellico: It's Complicated. Tennessee Valley Authority. [5 January 2022].

- ^ Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill. United States Department of Justice. April 13, 2015 [May 18, 2021].

- ^ Trieu, Cat. Remembering the 1982 World's Fair. The Daily Beacon (Knoxville: University of Tennessee). November 16, 2017 [2021-04-25].

- ^ McCrary, Amy. The world came to Knoxville in May 1982. Knoxville News Sentinel. May 28, 2016 [2021-04-24].

- ^ Fontenay, Blake. Shooting the Rapids: How a Small East Tennessee Community Struck Olympic Gold. Tennessee State Library. April 22, 2016 [June 4, 2021].

- ^ Greyhound Bus/Malone Freight Line, Inc. Truck Collision, U.S. Route 11W, Bean Station, Tennessee, May 13, 1972 (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. October 25, 1973 [May 6, 2020].

- ^ Lakin, Matt. Blood on the asphalt: 11W wreck left 14 people dead. Knoxville News Sentinel. August 26, 2012 [May 6, 2020].

- ^ National Transportation Safety Board. Multiple-vehicle collisions and fire during limited visibility (fog) on Interstate 75 near Calhoun, Tennessee December 11, 1990 (PDF) (报告). September 28, 1992 [February 25, 2021].

- ^ Forensic Files: Killer Fog (Season 2, Episode 3). IMDB. October 16, 1997 [January 12, 2019].

- ^ Sullivan, J.R . A Lawyer, 40 Dead Americans, and a Billion Gallons of Coal Sludge. Men's Journal. September 2019 [November 2, 2019]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-02).

- ^ Bourne, Joel K. Coal's other dark side: Toxic ash that can poison water, destroy life and toxify people. National Geographic. February 19, 2019 [2020-05-22].

- ^ Flessner, Dave. TVA to auction 62 parcels in Kingston after ash spill cleanup completed. Chattanooga Times Free Press (Chattanooga, TN). May 29, 2015 [2019-06-16]. (原始内容存档于June 16, 2019).

- ^ Cecil Sharp, Maud Karpeles (ed.), English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians (London: Oxford University Press, 1932), pp. 26, 77, 115, 183, 244, 310, etc.

- ^ Ted Olson and Ajay Kalra, "Appalachian Music: Examining Popular Assumptions". A Handbook to Appalachia: An Introduction to the Region (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 163-170.

- ^ White Lightning Guide (PDF). Tennessee Department of Tourism Development. [2 January 2022].

- ^ THE BALLAD OF DAVY CROCKETT - Lyrics - International Lyrics Playground. lyricsplayground.com.

- ^ DANIEL BOONE - Lyrics - International Lyrics Playground. lyricsplayground.com.

- ^ Daniel Boone Theme Song. Vimeo.

- ^ ScrambledEggs1969. Daniel Boone Theme Song 1964. October 10, 2012. (原始内容存档于2021-12-21) –通过YouTube.

- ^ Daniel Boone Theme Song. [March 20, 2010]. (原始内容存档于March 5, 2010).

- ^ Mingo. June 28, 2008 [March 20, 2010]. (原始内容存档于May 29, 2010).

- ^ "One Week Out: Events coming next weekend," The Daily Times (Maryville, TN), June 13, 2008, Weekend section: "Although Cutter Gap does not exist, it is widely believed that Marshall based the village on the real community of Morgan Branch in nearby Cocke County. Townsend served as Cutter Gap for the popular CBS television series 'Christy' in the mid-1990s."

- ^ Amazing Grace. May 5, 1994 –通过www.imdb.com.

- ^ Beta Hi-Fi Archive. JUDY COLLINS - "Christy" TV Series, "Down In the Valley". September 29, 2009. (原始内容存档于2021-12-21) –通过YouTube.

- ^ Christy, the Musical. Big Walnut Productions. [November 6, 2016]. (原始内容存档于October 18, 2016).

- ^ Religious/Inspirational - Read North Carolina Novels. blogs.lib.unc.edu.

- ^ Christy Fest - Townsend, TN. www.americantowns.com.

- ^ Dolly Parton, Katy Perry to Duet on ACM Awards. Rolling Stone. March 21, 2016.

- ^ Guttman, Amy. Moonshine As Moneymaker? Eastern Tennessee Will Drink To That. NPR (Washington, D.C.). June 27, 2013 [June 6, 2021].

- ^ Gaines, Jim. Tennessee boat industry thriving as buyers seek sport and luxury. Knoxville News Sentinel. May 30, 2019 [June 6, 2021].

- ^ Solving Big Problems (PDF). Oak Ridge National Laboratory. June 2013 [May 28, 2021].

- ^ Department of Energy FY 2020 Congressional Budget Request (PDF). Department of Energy. March 2019 [September 30, 2020].

- ^ Sherman, Erik. Tennessee's Tech Corridor. ComputerWorld. July 27, 2000 [May 27, 2021].

- ^ Chattanooga Gig: Your Gig is Here.. chattanoogagig.com.

- ^ Wyatt, Edward. Fast Internet Is Chattanooga's New Locomotive. The New York Times. February 3, 2014.

- ^ Mansfield, Duncan. Tenn. Nuclear Fuel Problems Kept Secret. The Guardian (London). August 20, 2007 [2007-08-21]. (原始内容存档于2007-10-30).

- ^ Campbell, Paige. Nuclear Confusion. The Appalachian Voice. February 21, 2012 [January 19, 2022].

- ^ Blau, Max. First new US nuclear reactor in 20 years goes live. CNN (Cable News Network. Turner Broadcasting System, Inc.). 2016-10-20 [2016-10-20].

- ^ Mooney, Chris. It's the first new U.S. nuclear reactor in decades. And climate change has made that a very big deal. The Washington Post. June 17, 2016 [June 4, 2020].

- ^ ORNL, TVA sign agreement to collaborate on advanced reactor technologies. Oak Ridge National Laboratory. February 19, 2020 [October 7, 2020].

- ^ Thompson, Tommy. Zinc Deposits in East Tennessee. Society of Economic Geologists Guidebook Series (Society of Economic Geologists). January 1, 1992, 14 [5 January 2022]. ISBN 9781934969670. doi:10.5382/GB.14.Ch1.

- ^ 167.0 167.1 Powell, Wayne G. Tennessee Marble. [20 November 2011].

- ^ "Ask Doc Knox," "What's With All This 'Marble City' Business?" Metro Pulse 10 May 2010. Accessed at the Internet Archive, 5 October 2015.

- ^ Rhodes, Elizabeth; Romano, Andrea. These Are the Best Theme Parks in the United States. Travel + Leisure. [January 30, 2021].