基督教對酒的觀點

基督教對酒的觀點有許多,基督教千餘年的歷史中,基督教徒將酒精飲料作為日常生活中不可缺少的一部份,在聖餐中幾乎總是飲用葡萄酒[1][2]。依據《聖經》和基督教傳統,認為酒是神的禮物,可以使到生活更加快樂,但是酗酒所導致的醉酒是一種罪[3][4]。在19世紀中期,出現對酒精消費持着溫和主義的教徒外,也出現了迴避主義及禁酒主義的新教徒[5]。今日,上述三種主義都存在於基督教,但是溫和主義仍然佔據多數,例如英國國教、天主教、東正教及相當大一部份的新教。

聖經中的酒

[編輯]酒精飲料頻繁出現在聖經之中。一方面它可以帶來歡樂的神的祝福,另一方面它也可能導致人失去理智或對他人施虐[6][7][8]。基督教對酒的觀點大多基於聖經,以及猶太人及基督教傳統。聖經語言中有數個單詞代表酒精飲料[4][9],同時儘管一些禁酒主義和迴避主義者有不同的看法[10][11][12][13],但通常都認為這些單詞最初並不是指會使人喝醉的飲料[4][6][8][14][15][16][17]。

在聖經中描繪的日常生活里頻繁出現的葡萄酒總有着積極或消極的隱喻意味[18][19]。從積極的方面來講,葡萄酒是豐産和聖血的象徵[20],反之,他也是嘲諷者的象徵[21],滿飲一杯烈性葡萄酒有時可能會是上帝的審判或憤怒的象徵[22]。

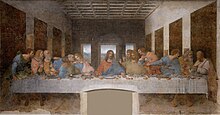

聖經中曾提及葡萄酒會帶來歡愉[23]。舊約中葡萄酒用在祭儀和節日慶祝上[4]。福音書中載耶穌的第一個神跡是在迦拿的婚禮上[24],造出了大量的葡萄酒[25],當在最後的晚餐上享用聖餐時[26],他說葡萄酒[27][28]是「用(他的)血所立的新約」[29],不過在這一點的具體所指上還存在爭議[30]。在聖經時代,酒也作醫療用途,例如口服麻醉劑[31]、局部清潔劑[32]以及助消化[33]。

舊約裏的國王和神父在很多時候都不可以飲用葡萄酒[34],一些時候連醋、葡萄和葡萄乾都不可以享用[35][36][37]。聖保羅進一步指出了基督教徒對於未成熟的基督教徒們的責任:「若是吃肉和飲葡萄酒會造成你的兄弟們墮落,就不要去做這様的事」[38]。

實際上所有的基督教派都同意聖經確實在很多章中都對醉酒進行了譴責[39],《伊斯頓的聖經詞典》中說:

| “ | 醉酒之罪……在古時並非不常見,在聖經中被直接指代以及用來作為隱喻而出現了七十次以上。 | ” |

[4]此外,諾亞[40]和羅得[41]醉酒的後果也被用來警告他人不要酗酒[42],而且聖保羅也因科林斯人在聖餐慶典上醉酒而責駡過他們[43]。對幾乎所有的基督教徒來說,醉酒不僅僅是一種令人厭惡的個人和社會陋習,同時也擋住了天堂大門,褻瀆了棲居著聖靈的身體以及教會[3]。

聖經時代的葡萄酒釀造

[編輯]巴勒斯坦的氣候和土地都很適宜種植葡萄[44],當時葡萄酒是一種重要的商品[45][46]。葡萄園有圍牆、籬笆以及瞭望塔守衛,以防強盜及動物的威脅[47]。

葡萄的豐收帶來歡樂[48][49][50],一些收穫的葡萄會被馬上吃掉,而其他的則被製成葡萄乾以及釀成葡萄酒[49]。

釀造葡萄酒時,在壓榨之後就開始進行發酵,並被倒入巨大的陶罐中密封保存。如果需要運輸,則倒入葡萄酒囊(一般由鞣製的山羊皮製成)中[44]。數星期後後發酵完畢,被倒入更大容器里貯藏後者直接外售[49][51]。通常當時的葡萄酒中會加入香料等物質以掩蓋其缺陷[52]。

基督教歷史和傳統中的酒精

[編輯]基督之前

[編輯]基督之前希伯來人認為葡萄酒是神創造的這個世界的一部份,因此雖然過度飲酒會帶來危害,但他「必然本來就是好的」[54],猶太人也更強調快樂而不是節欲[55]。

直到巴比倫之囚(大約公元前537年左右)後和舊約結束時,葡萄酒一直都是「各年齡段和各階層中的常見飲品、營養的重要來源、節日中最重要的成份、一種被廣泛認可的藥物、任何要塞的供應品以及重要的商品」,被當做「希伯來人生活中不可少的一個元素」[56]。安息日的終節儀式上、割禮、逾越節和婚禮上也會用到葡萄酒[57]。

有些人認為在聖經中葡萄酒常是被用水稀釋來減弱其效力的[13],但是一般觀點是聖經中的葡萄酒雖有時混合香料來提味,但不常用水稀釋[58][59][60],並且摻水的葡萄酒在舊約中是腐敗的隱喻[61]。但是希臘人卻常在酒中加水以減弱其效力並改善口感[62],在馬加比二書(約公元前二到一世紀)的時代,亞歷山大大帝征服了巴勒斯坦,猶太人也很大程度上接受了一些希臘文化[59][63],並將之帶入新約時代的猶太人祭儀中[64][65]。

古羅馬時期,龐培再次征服巴勒斯坦,並設猶太行省,當地人也成為羅馬公民,按規定每個普通成年公民每天可以喝大約1升葡萄酒[66],不過那時相對葡萄酒來說,啤酒則更為常見 [67]。

基督教早期

[編輯]使徒教父們很少提及葡萄酒[68],但是基督教早期教父明確提及早期基督教在聖餐上會使用葡萄酒,並依據流行風俗兌水[69][70]。《提摩太前書》中保羅建議身體不適的提摩太可以喝一點酒。十二使徒遺訓中命令基督教徒分出一部份的葡萄酒以支持一位真正的先知,如果他們沒有先知的話則分給窮人[71]。

亞歷山太的革利免(死於約215年)曾寫道,他很讚賞那些生活作風嚴肅,能節制飲酒的人,並建議年輕人要節制飲酒以免點燃他們的「野性激情」,但是並不排斥用酒做藥,在一天的工作後小酌兩口也是可以接受的[72][73]。

居普良(死於258年)認為像諾斯底主義信徒那樣在聖餐中以水代酒違背了「福音派和使徒的準則」,不過他也反對醉酒[74]。

約翰一世(死於407年)強調飲酒適度,並駁斥了一些異教徒和基督教徒認為不應有葡萄酒存在的觀點,他說

| “ | 不應該醉酒;葡萄酒是神的禮物,而醉酒則屬於魔鬼。葡萄酒不會令人喝醉,但是不節制卻會這樣。不要將之歸咎於神的手藝,這是凡人的愚行 | ” |

因此,節制這一觀點從希臘哲學中逐漸滲入基督教倫理學,並成為安波羅修[77]和希波的奧古斯丁[78][79]所推崇的四樞德之一。相反,醉酒則被認為屬於七宗罪之一的貪食[80]。

中世紀

[編輯]

羅馬帝國的衰落使得西歐和中歐葡萄酒的生產和消費大受影響,不過教會(特別是在拜占庭)依舊保存下了葡萄栽培和葡萄酒釀製的技術[81]。

中世紀的僧侶是成功的啤酒和葡萄酒釀造人之一[82],同時他們每天被允許可以喝5升啤酒,並且齋戒期間也可以飲用啤酒[83][84]。聖本篤(死於547年)創立的聖本篤會規中偏向認為僧侶每日應無葡萄酒,同時也相信戒酒是抑制物慾的通途[85]。但是他本人也曾指出這是令人不愉快的。故而聖本篤做了讓步,認為每日可以飲用四分之一升(或半升)的葡萄酒[86] 特殊情況下可以更多,[87],同時禁酒也成為了一項懲罰措施[88]。

托馬斯·阿奎那(死於1274年)認為適度飲酒不影響被救贖,但是特定的某些人需要完全戒酒[89]。他認為聖餐上一定要有葡萄酒,同時未發酵的葡萄汁也被當做是葡萄酒——因為它可以自然轉變成後者[90]。

1319年,貝爾納多·托洛梅伊最初堅持比本篤會更嚴格的禁慾規則。其追隨者是「狂熱的完全禁慾者」,甚至摧毀了他們自己的葡萄園,但這相關規章不久便被修改了[91]。

因為天主教聖餐飲用的需要[92],除了一些酒精過敏的僧侶[93],傳教士將葡萄種植技術帶到了幾乎所有他們能抵達的地方,以生產葡萄酒並用以進行彌撒[82]。天主教有許多早期和中世紀聖人都與酒有關,例如啤酒的主保聖人聖艾德里安、釀酒者和酒保以及葡萄酒商人的主保聖人聖阿曼德、都爾的瑪爾定以及葡萄酒商的主保聖人聖文森特[82]。

在東正教,除去聖餐之外,其他一些儀式也需要用到葡萄酒。在聖餐之後,信徒們會飲用一杯溫葡萄酒。不過在大多是齋日東正教圖都是不可以喝葡萄酒的,聖特立馮是葡萄園工人的主保聖人。在塞爾維亞東正教會中,葡萄就會被用在慶祝一個叫做Slava的節日[94]。

宗教改革

[編輯]在宗教改革中,從馬丁·路德、約翰·加爾文到慈運理、約翰·諾克斯都支持在儀式中使用葡萄酒[95],加爾文本人在日內瓦的年薪中就包括幾桶葡萄酒[96]。路德會協和信條(1576年)[97]、衛理公會教綱(1784年)[98]和再洗禮派[99][100][101][102]也都支持使用葡萄酒。英國清教徒也支持飲用葡萄酒和麥芽酒[103]。

美洲殖民地

[編輯]最初前往美洲的移民幾乎每人都帶着一定數量的酒[104],並將之用於幾乎任何領域,包括神職授任、葬禮等等[105]。美洲殖民地牧師、哈佛大學校長英克里斯·馬瑟在一次佈道時說:[106]

| “ | 飲酒本身是上帝的一個好的造物,我們應懷着感激的心去接受他,但是酗酒卻是來自撒旦。 | ” |

衛理公會

[編輯]約翰·衛斯理認為烈酒,例如白蘭地和威士忌不應用於除醫療外的其他地方,並且說不加選擇地將蒸餾器賣給他人甚於神譴的毒藥和謀殺[107]。1744年,衛斯理給衛理公會下的一些組織的指示中要求他們「不品嘗任何含酒精的液體……除非有醫師許可」[108]。1780年,在巴爾的摩的一場衛斯理工會會議上,教徒公開反對烈酒生產並決定與不願放棄生產烈酒的人脫離關係[109]。在第一波美國禁酒運動之後,他們將戒酒的範圍擴展到了除烈酒之外的其他酒精飲料[109][110]。

衛斯理的宗教會規在1784年被美國的美以美會接受了,承認葡萄酒可用於聖餐並且任何人都可以享用[111]。

禁酒運動

[編輯]很多大規模的禁酒運動都是在19世紀之後發起的,而它們又多數只是反烈酒[112],在反對者看來烈酒更便宜也更容易使人醉酒,同時也並不都反對適當飲用其他的酒精飲料。然而隨着美洲大陸第二次大覺醒的發生,禁酒運動也逐漸開始排斥一切酒精飲料了[113][114][115]。

最終的結果是酒開始被厭棄,以至於開始從聖餐等宗教儀式中逐漸減少了[113][116],然而在許多教會中葡萄酒這樣的葡萄釀造的酒還是很受歡迎的,而一些教會則宣稱需要在聖餐中使用「未發酵的酒」[117],因此一些禁酒者開始用濃縮葡萄汁取代葡萄酒[118]。1869年,托馬斯·布拉姆韋爾·韋爾奇[119]找到了利用巴士德消毒法保存葡萄汁的方法,這樣教會就可以方便地在聖餐中使用葡萄汁而不必擔憂其腐敗問題了。

1838年至1845年,愛爾蘭禁酒人士、神父西奧博爾德·馬修一共對大約三到四百萬人做了禁酒宣傳,並和一些美國人形成了許多禁酒團體,但是其影響力卻十分有限。1872年,美國基督教完全禁酒聯盟聯合這些團體成立,1913年其會員達到90,000人,其中不乏青少年和女性,其宗旨是通過說服普通人而不是利用政治手段來達成目的,其行為受到了兩任天主教教宗利奧十三世(1878年)和庇護十世(1906年)的贊許[120]。不過也有相當的反對聲音,例如密爾沃基的大主教塞巴斯蒂安·傑拉爾德·梅斯梅爾公開譴責禁酒運動遵循了「絕對錯誤的準則」並蓄意破壞教會「最神聖的秘密」——即聖餐,並且禁止他主教教區內的神父支持禁酒運動,而建議他們採取溫和的態度[121]。最終,天主教教義並沒有受到禁酒運動太大的影響[122][123]。

路德教和英國國教也沒有轉變它們的中立地位,甚至英國的宗教禁酒團體事實上也不完全主張禁酒[124]。而其他的教會則頻繁出現在禁酒的舞臺上[125][126],許多衛理公會、浸信會和長老會教徒都支持絕對禁酒[127]。

20世紀早期禁酒運動達到高峰,隨後便開始衰落[128]。相對美國來說,不列顛群島、北歐和其他一些地區禁酒運動的影響就更加微弱[126][129]。

現今

[編輯]現在,基督教關於酒的觀點大致可分為溫和主義、迴避主義和禁酒主義。後二者觀點有相似之處,其區別在於前者支持利用理智來達成禁酒的目的,而後者則偏向利用法律[5]。

溫和主義

[編輯]持該觀點的是羅馬天主教[130]、東正教[131]、聖公會[8] 以及諸多新教教派,路德教[132][133]、耶和華見證會[134] 和改革宗也接受這一觀點[135][136][137][138][139]。

溫和主義認為根據聖經和傳統智慧,酒是神賜的禮物,就算有危險性,也應該採取溫和和理智的態度而不是完全否定他[113][140][141],他們也認為節制比禁慾更符合聖經規範[142][143]。

大體上所有的持溫和主義的教派都支持在聖餐中使用葡萄酒[92][93],不過由於禁酒主義者的影響和部份人的過敏體質問題,也會提供葡萄汁來代替葡萄酒[132][136][137][144],一些基督教徒會按照古代傳統在酒中兌水[145][146]。

迴避主義

[編輯]持這一觀點的教派是浸信會[147]、五旬節派[148]、衛理公會[149]以及其他福音派教會和包括救世軍在內的一些新教組織[150]。迴避主義的著名支持者有葛培理[151]、約翰·F·麥克阿瑟[152]、阿爾伯特·莫勒[153]和約翰·派博[154]。

迴避主義者相信儘管酒精消費本身不是邪惡的,也不需要在任何場合都迴避,但他還是一個不明智的,或者不是最謹慎的選擇[155]。儘管他們不需要禁止自己飲酒以保證在教會內的地位,但是高層人士還須注意[17][154][156]。

迴避主義者認為聖經中有警告酒會影響人的道德判斷立[157],如果執意飲酒也可能會造成異見者之間的矛盾從而進一步影響基督教的統一和教徒間的友愛[158],同時因為酒會帶來不好的影響故而必須要反對,一些迴避主義者認為這可以提升自己的品德[156][157]。

此外,他們認為雖然在古代飲酒是更容易接受的[17][159],但是現在的環境已然不同了。他們認為在聖經時代的葡萄酒沒有現在這麼強烈,並且因為會兌水所以更不容易喝醉[160][161][162],不過有一些非迴避主義者認為這個論據並不十分可靠[58][59][143],同時現在的經濟和技術都大不一樣,故而兩者是不能相提並論的[161][163]。

禁酒主義

[編輯]自禁酒運動衰退之後,持禁酒主義的人數便逐漸減少。依舊持該論點的教會和組織有南美浸信會[164][165]和基督復臨教派[166][167]。救世軍的創始人卜威廉就是一位禁酒主義者[168],不過他所成立的組織現在已經改持迴避主義了[150]。

禁酒主義者例如史蒂芬·M·雷諾茲[169][170][171] 和Jack Van Impe[172]都認為聖經禁止了飲酒,認為聖經中的一個章節[173]里所提到的用來療傷的酒實際上是未發酵的葡萄汁[12],且實際上聖經中提及的所謂的酒精飲料實際上真實性還待定[11][171]。一些禁酒主義者認為聖經中翻譯的相關詞彙存在偏差[12][171]。

後期聖徒運動中最大的團體耶穌基督後期聖徒教會也認為神曾經說過反對酒精的使用[174][175]。他們的依據主要是摩爾門教正典《教義和聖約》中的智慧之言,儘管其中有提到在類似於聖餐的聖禮中可以使用葡萄酒[176],但摩爾門教現在已在該儀式中換用了水[177]。

參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ R. V. Pierard. Alcohol, Drinking of. Walter A. Elwell (編). Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House: 28f. 1984. ISBN 0-8010-3413-2.

- ^ F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone (編). Wine. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, USA: 1767. 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

[W]ine has traditionally been held to be one of the essential materials for a valid Eucharist, though some have argued that unfermented grape-juice fulfils the Dominical [that is, Jesus'] command.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Raymond, p. 90.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Wine. Easton's Bible Dictionary. 1897 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-28).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Kenneth Gentry. God Gave Wine. Oakdown. 2001: 3ff. ISBN 0-9700326-6-8.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Bruce Waltke. Commentary on 20:1. The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 15-31. Wm. B. Eerdmans. 2005: 127. ISBN 978-0-8028-2776-0.

? F. S. Fitzsimmonds. Wine and Strong Drink. J. D. Douglas (編). New Bible Dictionary 2nd ed. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press: 1255. 1982. ISBN 0-8308-1441-8.These two aspects of wine, its use and its abuse, its benefits and its curse, its acceptance in God's sight and its abhorrence, are interwoven into the fabric of the [Old Testament] so that it may gladden the heart of man (Ps. 104:15) or cause his mind to err (Is. 28:7), it can be associated with merriment (Ec. 10:19) or with anger (Is. 5:11), it can be used to uncover the shame of Noah (Gn. 9:21) or in the hands of Melchizedek to honor Abraham (Gn. 14:18) ... The references [to alcohol] in the [New Testament] are very much fewer in number, but once more the good and the bad aspects are equally apparent ...

? D. Miall Edwards. Drunkenness. James Orr (編). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. 1915b [2007-03-09]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).[Wine's] value is recognized as a cheering beverage (Jdg 9:13; Ps 104:15; Prov 31:7), which enables the sick to forget their pains (Prov 31:6). Moderation, however, is strongly inculcated and there are frequent warnings against the temptation and perils of the cup.

? John McClintock and James Strong (eds.). Wine. Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature X. New York: Harper and Brothers: 1016. 1891 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-30).But while liberty to use wine, as well as every other earthly blessing, is conceded and maintained in the Bible, yet all abuse of it is solemnly condemned.

- ^ I. W. Raymond. The Teaching of the Early Church on the Use of Wine and Strong Drink. AMS Press. 1970: 25 [1927]. ISBN 978-0-404-51286-6.

This favorable view [of wine in the Bible], however, is balanced by an unfavorable estimate ... The reason for the presence of these two conflicting opinions on the nature of wine [is that the] consequences of wine drinking follow its use and not its nature. Happy results ensue when it is drunk in its proper measure and evil results when it is drunk to excess. The nature of wine is indifferent.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Ethical Investment Advisory Group. Alcohol: An inappropriate investment for the Church of England (PDF). Church of England. January 2005 [2007-02-08]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2007-02-26).

Christians who are committed to total abstinence have sometimes interpreted biblical references to wine as meaning unfermented grape juice, but this is surely inconsistent with the recognition of both good and evil in the biblical attitude to wine. It is self-evident that human choice plays a crucial role in the use or abuse of alcohol.

- ^ Fitzsimmonds, pp. 1254f.

- ^ Stephen M. Reynolds. The Biblical Approach to Alcohol. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 1989.

[W]herever oinos [Greek for 'wine'] appears in the New Testament, we may understand it as unfermented grape juice unless the passage clearly indicates that the inspired writer was speaking of an intoxicating drink.

? Stuart, Moses. Encyclopedia of Temperance and Prohibition. New York: Funk and Wagnalls: 621. 1891.Wherever the Scriptures speak of wine as a comfort, a blessing or a libation to God, and rank it with such articles as corn and oil, they mean—they can mean only—such wine as contained no alcohol that could have a mischievous tendency; that wherever they denounce it, prohibit it and connect it with drunkenness and reveling, they can mean only alcoholic or intoxicating wines.

Quoted in Reynolds, The Biblical Approach to Alcohol. - ^ 11.0 11.1 Ralph Earle. 1 Timothy 5:13. Word Meanings in the New Testament. Kansas City, Missouri: Beacon Hill Press. 1986. ISBN 0-8341-1176-4.

Oinos is used in the Septuagint for both fermented and unfermented grape juice. Since it can mean either one, it is valid to insist that in some cases it may simply mean grape juice and not fermented wine.

? Dave Miller. Elders, Deacons, Timothy, and Wine. Apologetics Press. 2003 [2008-03-25]. (原始內容存檔於2008-04-08).The term oinos was used by the Greeks to refer to unfermented grape juice every bit as much as fermented juice. Consequently, the interpreter must examine the biblical context in order to determine whether fermented or unfermented liquid is intended.

? Frederic Richard Lees; Dawson Burns. Appendix C-D. The Temperance Bible-Commentary. New York: National Temperance Society and Publication House. 1870: 431–446.

? William Patton. Christ Eating and Drinking. Laws of Fermentation and the Wines of the Ancients. New York: National Temperance Society and Publication House. 1871: 79 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2008-06-21).Oinos is a generic word, and, as such, includes all kinds of wine and all stages of the juice of the grape, and sometimes the clusters and even the vine ...

? G. A. McLauchlin. Commentary on Saint John. Salem, Ohio: Convention Book Store H. E. Schmul. 1973: 32 [1913].There were ... two kinds of wine. We have no reason to believe that Jesus used the fermented wine unless we can prove it ... God is making unfermented wine and putting in skin cases and hanging it upon the vines in clusters every year.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Samuele Bacchiocchi. A Preview of Wine in the Bible. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-02-02). 引用錯誤:帶有name屬性「Bacchiocchi」的

<ref>標籤用不同內容定義了多次 - ^ 13.0 13.1 John MacArthur. Living in the Spirit: Be Not Drunk with Wine--Part 2. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2015-09-23).

- ^ W. Ewing. Wine. James Hastings (編). Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels 2. Edinburgh: T & T Clark: 824. 1913 [2007-03-14]. (原始內容存檔於2017-08-16).

There is nothing known in the East of anything called 'wine' which is unfermented ... [The Palestinian Jews'] attitude towards the drinker of unfermented grape juice may be gathered from the saying in Pirke Aboth (iv. 28), 'He who learns from the young, to what is he like? to one who eats unripe grapes and drinks wine from his vat [that is, unfermented juice].'

(Emphasis in original.)

? Charles Hodge. The Lord’s Supper. Systematic Theology. Wm. B. Eerdmans. 1940: 3:616 [1872] [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2006-01-10).That [oinos] in the Bible, when unqualified by such terms as new, or sweet, means the fermented juice of the grape, is hardly an open question. It has never been questioned in the Church, if we except a few Christians of the present day. And it may safely be said that there is not a scholar on the continent of Europe, who has the least doubt on the subject.

? A. A. Hodge. Evangelical Theology. : 347f.'Wine,' according to the absolutely unanimous, unexceptional testimony of every scholar and missionary, is in its essence 'fermented grape juice.' Nothing else is wine ... There has been absolutely universal consent on this subject in the Christian Church until modern times, when the practice has been opposed, not upon change of evidence, but solely on prudential considerations.

Quoted in Keith Mathison. Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 3: Historic Reformed & Baptist Testimony. IIIM Magazine Online. January 8 to January 14, 2001, 3 (2) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27). - ^ W. J. Beecher. Total abstinence. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: 472. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-08-16).

The Scriptures, rightly understood, are thus the strongest bulwark of a true doctrine of total abstinence, so false exegesis of the Scriptures by temperance advocates, including false theories of unfermented wine, have done more than almost anything else to discredit the good cause. The full abandonment of these bad premises would strengthen the cause immeasurably.

- ^ William Kaiser and Duane Garrett (編). Wine and Alcoholic Beverages in the Ancient World. Archaeological Study Bible. Zondervan. 2006. ISBN 978-0-310-92605-4.

[T]here is no basis for suggesting that either the Greek or the Hebrew terms for wine refer to unfermented grape juice.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 John F. MacArthur. GC 70-11: "Bible Questions and Answers". [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-03).

? Pierard, p. 28: "No evidence whatsoever exists to support the notion that the wine mentioned in the Bible was unfermented grape juice. When juice is referred to, it is not called wine (Gen. 40:11 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)). Nor can 'new wine' ... mean unfermented juice, because the process of chemical change begins almost immediately after pressing." - ^ W. Dommershausen. Yayin. G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren (編). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament VI. trans. David E. Green. Wm. B. Eerdmans: 64. 1990. ISBN 0-8028-2330-0.

- ^ Raymond, p. 24: "The numerous allusions to the vine and wine in the Old Testament furnish an admirable basis for the study of its estimation among the people at large."

- ^ Ge 27:28; 49:9-12; Dt 7:13; 11:14; 15:14; compare 33:28; Pr 3:9f; Jr 31:10-12; Ho 2:21-22; Jl 2:19,24; 3:18; Am 9:13f; compare 2Ki 18:31-32; 2Ch 32:28; Ne 5:11; 13:12 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館); etc.

- ^ Pr 20:1. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-27).

- ^ Ps 60:3; 75:8; Is 51:17-23; 63:6; Jr 13:12-14; 25:15-29; 49:12; 51:7; La 4:21f; Ezk 23:28-33; Na 1:9f; Hab 2:15f; Zc 12:2; Mt 20:22; 26:39, 42; Lk 22:42; Jn 18:11; Re 14:10; 16:19 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館); compare Ps Sol 8:14 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Jg 9:13; Ps 4:7; 104:15; Ec 9:7; 10:19; Zc 9:17; 10:7. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Jn 2:1-11; 4:46. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Six pots of thirty-nine liters each = 234 liters = 61.8 gallons, according to Heinrich Seesemann. οινο?. Gerhard Kittel and Ronald E. Pitkin (編). Theological Dictionary of the New Testament V. trans. Geoffrey W. Bromiley. Wm. B. Eerdmans: 163. 1967. ISBN 0-8028-2247-9.

- ^ Mt 26:17-19; Mk 14:12-16; Lk 22:7-13 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). The Gospel of John offers some difficulties when compared with the Synoptists' accounts on whether the meal was part of the Passover proper. In any case, it seems that the Last Supper was most likely somehow associated with Passover, even if it wasn't the paschal feast itself. See the discussion in Leon Morris. Additional Note H: The Last Supper and the Passover. The Gospel According to John. New International Commentary on the New Testament revised. Wm. B. Eerdmans. 1995: 684–695. ISBN 978-0-8028-2504-9.

- ^ Seesemann, p. 162: "Wine is specifically mentioned as an integral part of the passover meal no earlier than Jub. 49:6 ['... all Israel was eating the flesh of the paschal lamb, and drinking the wine ...'], but there can be no doubt that it was in use long before." P. 164: "In the accounts of the Last Supper the term [wine] occurs neither in the Synoptists nor Paul. It is obvious, however, that according to custom Jesus was proffering wine in the cup over which He pronounced the blessing; this may be seen especially from the solemn [fruit of the vine] (Mark 14:25 and par.) which was borrowed from Judaism." Compare "fruit of the vine" as a formula in the Mishnah, Tractate Berakoth 6.1. [2007-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2007-01-26).

- ^ Raymond, p. 80: "All the wines used in basic religious services in Palestine were fermented."

- ^ Mt 26:26-29; Mk 14:22-25; Lk 22:17-20; 1 Co 10:16; 11:23-25. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-08).

- ^ Bruce Lincoln. Beverages. Lindsay Jones (編). Encyclopedia of Religion 2 2nd ed. MacMillan Reference Books: 848. 2005. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

- ^ Pr 31:4-7; Mt 27:34,48; Mk 15:23,36; Lk 23:36; Jn 19:28–30. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Lk 10:34. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ 1 Ti 5:23. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Pr 31:4f; Lv 10:9; compare Ez 44:21. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-16).

- ^ Nu 6:2-4 (compare Jg 13:4-5; Am 2:11f); Jr 35. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-16).

- ^ Mt 11:18f; Lk 7:33f; compare Mk 14:25; Lk 22:17f. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2018-01-16).

- ^ I. W. Raymond p. 81: "Not only did Jesus Christ Himself use and sanction the use of wine but also ... He saw nothing intrinsically evil in wine.[footnote citing Mt 15:11 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) ]"

- ^ Ro 14:21 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館). Raymond understands this to mean that "if an individual by drinking wine either causes others to err through his example or abets a social evil which causes others to succumb to its temptations, then in the interests of Christian love he ought to forego the temporary pleasures of drinking in the interests of heavenly treasures" (p. 87).

- ^ For instance, Pr 20:1; Is 5:11f; Ho 5:2,5; Ro 13:13; Ep 5:18; 1 Ti 3:2-3 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Ge 9:20-27. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Ge 19:31-38. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Magen Broshi. Wine in Ancient Palestine — Introductory Notes. Israel Museum Journal. 1984, III: 33.

- ^ 1Co 11:20-22. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Ewing, p. 824.

- ^ See Broshi, passim (for instance, p. 29: Palestine was "a country known for its good wines").

- ^ Compare 2Ch 2:3,10 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Ps 80:8-15; Is 5:1f; Mk 12:1; compare SS 2:15. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-24).

- ^ Compare Is 16:10; Jr 48:33. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2019-05-23).

- ^ 49.0 49.1 49.2 Wine Making. Illustrated Dictionary of Bible Life & Times: 374f.

- ^ Broshi, p. 24.

- ^ Broshi, p. 26.

- ^ Broshi, p. 27.

- ^ Dt 16:13-15. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2019-05-23).

- ^ Raymond, p. 48.

- ^ Raymond, p. 49.

- ^ David J. Hanson. Preventing Alcohol Abuse: Alcohol, Culture and Control. Westport, CT: Praeger. 1995: 4. ISBN 978-0-275-94926-6.

? Magen Broshi. The Diet of Palestine in the Roman Period — Introductory Notes. Israel Museum Journal. 1986, V: 46.In the biblical description of the agricultural products of the Land, the triad 'cereal, wine, and oil' recurs repeatedly (Deut. 28:51 and elsewhere). These were the main products of ancient Palestine, in order of importance. The fruit of the vine was consumed both fresh and dried (raisins), but it was primarily consumed as wine. Wine was, in antiquity, an important food and not just an embellishment to a feast ... Wine was essentially a man's drink in antiquity, when it became a significant dietary component. Even slaves were given a generous wine ration. Scholars estimate that in ancient Rome an adult consumed a liter of wine daily. Even a minimal estimate of 700g. per day means that wine constituted about one quarter of the caloric intake (600 out of 2,500 cal.) and about one third of the minimum required intake of iron.

? Raymond, p. 23: "[Wine] was a common beverage for all classes and ages, even for the very young. Wine might be part of the simpelest meal as well as a necessary article in the households of the rich.

? Geoffrey Wigoder; et al (編). Wine. The New Encyclopedia of Judaism. New York University Press: 798f. 2002. ISBN 978-0-8147-9388-6.As a beverage, it regularly accompanied the main meal of the day. Wherever the Bible mentions 'cup' — for example, 'my cup brims over' (Ps. 23:5)—the reference is to a cup of wine ... In the talmudic epoch ... [i]t was customary to dilute wine before drinking by adding one-third water. The main meal of the day, taken in the evening (only breakfast and supper were eaten in talmudic times), consisted of two courses, with each of which a cup of wine was drunk.

- ^ Wigoder, p. 799.

- ^ 58.0 58.1 Gentry, God Gave Wine, pp. 143-146: "[R]ecognized biblical scholars of every stripe are in virtual agreement on the nondiluted nature of wine in the Old Testament."

- ^ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Burton Scott Easton. Wine; Wine Press. James Orr (編). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. 1915 [2007-03-09]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

In Old Testament times wine was drunk undiluted, and wine mixed with water was thought to be ruined (Isa 1:22) ... At a later period, however, the Greek use of diluted wines had attained such sway that the writer of 2 Maccabees speaks (15:39) of undiluted wine as 'distasteful' (polemion). This dilution is so normal in the following centuries that the Mishna can take it for granted and, indeed, R. Eliezer even forbade saying the table-blessing over undiluted wine (Berakhoth 7 5). The proportion of water was large, only one-third or one-fourth of the total mixture being wine (Niddah 2 7; Pesachim 108b).

- ^ Clarke, commentary on Is 1:22: "It is remarkable that whereas the Greeks and Latins by mixed wine always understood wine diluted and lowered with water, the Hebrews on the contrary generally mean by it wine made stronger and more inebriating by the addition of higher and more powerful ingredients, such as honey, spices, defrutum, (or wine inspissated by boiling it down to two-thirds or one- half of the quantity,) myrrh, mandragora, opiates, and other strong drugs."

- ^ Is 1:22. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Robert S. Rayburn. Revising the Practice of the Lord's Supper at Faith Presbyterian Church No. 2, Wine, No. 1. 2001-01-28 [2012-04-03]. (原始內容存檔於2012-10-15).

- ^ Dommershausen, p. 61: "The custom of drinking wine mixed with water—probably in the ratio of two or three to one—seems to have made its first appearance in the Hellenistic era."

? Archaeological Study Bible.Wine diluted with water was obviously considered to be of inferior quality (Isa.1:22), although the Greeks, considering the drinking of pure wine to be an excess, routinely diluted their wine.

? Raymond, p.47: "The regulations of the Jewish banquets in Hellenistic times follow the rules of Greek etiquette and custom."

? Compare 2 Mac 15:39 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2011-07-23. (Vulgate numbering: 2 Mac 15:40 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)) - ^ Compare the later Jewish views described in Wine. Jewish Encyclopedia. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2011-06-29).

- ^ Merrill F. Unger. Wine. Unger's Bible Dictionary 3rd ed. Chicago: Moody Press: 1169. 1981 [1966].

The use of wine at the paschal feast [that is, Passover] was not enjoined by the law, but had become an established custom, at all events in the post-Babylonian period. The wine was mixed with warm water on these occasions.... Hence the in the early Christian Church it was usual to mix the sacramental wine with water.

- ^ Broshi, p. 33.

- ^ Broshi, p. 22.

- ^ Raymond, p. 88.

- ^ Justin Martyr, First Apology, "Chapter LXV. Administration of the sacraments" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館) and "Chapter LXVII. Weekly worship of the Christians" (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Hippolytus of Rome (died 235) says, "By thanksgiving the bishop shall make the bread into an image of the body of Christ, and the cup of wine mingled with water according to the likeness of the blood." Quoted in Keith Mathison. Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 2: Historical Testimony. IIIM Magazine Online. January 1 to January 7, 2001, 3 (1) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

- ^ Didache, chapter 13. [2007-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2007年5月28日).

- ^ Clement of Alexandria. On Drinking. The Instructor, book 2, chapter 2. [2007-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-11).

- ^ Compare the summary in Raymond, pp. 97-104.

- ^ Cyprian. "Epistle LXII: To Caecilius, on the Sacrament of the Cup of the Lord", §11. [2007-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2007-02-25).

- ^ 1 Timothy 5:23. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ John Chrysostom. First Homily on the Statues: paras 11f. [2008-06-08]. (原始內容存檔於2017-06-21).

- ^ Ambrose. Book I, chapter XLIII. On the Duties of the Clergy. [2007-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2018-12-25).

- ^ Augustine of Hippo. Chapter 19. On the Morals of the Catholic Church. [2007-03-15]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-07).

- ^ Raymond, p. 78.

- ^ Gregory the Great. Moralia in Job, book 31, chapter 45.

- ^ Wine History. Macedonian Heritage. 2003 [2007-02-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-13).

- ^ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Jim West. Drinking with Calvin and Luther!. Oakdown Books. 2003: 22ff. ISBN 0-9700326-0-9.

- ^ Kevin Lynch. Sin & Tonic: Making beer, wine, and spirits is not the Devil’s work. The Wave Magazine. September 20 — October 3, 2006, 6 (19) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2006年11月12日).

- ^ Will Durant describes the customs of England in the late Middle Ages: "a gallon of beer per day was the usual allowance per person, even for nuns" (Will Durant. The Reformation. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1957: 113.)

- ^ Holy Rule of St. Benedict, Chapter XL.

- ^ That is, either about half a pint or a full pint. See Ancient Roman units of measurement - Liquid_measures and Theodore Maynard. Saint Benedict. Pillars of the Church. Ayer Publishing. 1945: 14. ISBN 0-8369-1940-8.

- ^ Benedict of Nursia. Chapter XL - Of the Quantity of Drink. Holy Rule of St. Benedict. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2013-04-24).

'Every one hath his proper gift from God, one after this manner and another after that' (1 Cor 7:7). It is with some hesitation, therefore, that we determine the measure of nourishment for others. However, making allowance for the weakness of the infirm, we think one hemina of wine a day is sufficient for each one. But to whom God granteth the endurance of abstinence, let them know that they will have their special reward. If the circumstances of the place, or the work, or the summer's heat should require more, let that depend on the judgment of the Superior, who must above all things see to it, that excess or drunkenness do not creep in.

- ^ Benedict of Nursia. Chapter XLIII - Of Those Who Are Tardy in Coming to the Work of God or to Table. Holy Rule of St. Benedict. [2008-04-18]. (原始內容存檔於2006-07-14).

If [a monk] doth not amend after [being twice tardy], let him not be permitted to eat at the common table; but separated from the company of all, let him eat alone, his portion of wine being taken from him, until he hath made satisfaction and hath amended.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. Second Part of the Second Part, Question 149, Article 3 - Whether the use of wine is altogether unlawful?. Summa Theologica. [2008-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2005-01-30).

A man may have wisdom in two ways. First, in a general way, according as it is sufficient for salvation: and in this way it is required, in order to have wisdom, not that a man abstain altogether from wine, but that he abstain from its immoderate use. Secondly, a man may have wisdom in some degree of perfection: and in this way, in order to receive wisdom perfectly, it is requisite for certain persons that they abstain altogether from wine, and this depends on circumstances of certain persons and places.

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. Third Part, Question 74, Article 5 - Whether wine of the grape is the proper matter of this sacrament?. Summa Theologica. [2008-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2005-02-26).

This sacrament can only be performed with wine from the grape.... Now that is properly called wine, which is drawn from the grape, whereas other liquors are called wine from resemblance to the wine of the grape.... Must, however, has already the species of wine, for its sweetness indicates fermentation which is 'the result of its natural heat' (Meteor. iv); consequently this sacrament can be made from must.... It is furthermore forbidden to offer must in the chalice, as soon as it has been squeezed from the grape, since this is unbecoming owing to the impurity of the must. But in case of necessity it may be done.

- ^ J. C. Almond. Olivetans. Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-25).

St. Bernard Ptolomei's idea of monastic reform was that which had inspired every founder of an order or congregation since the days of St. Benedict—a return to the primitive life of solitude and austerity. Severe corporal mortifications were ordained by rule and inflicted in public. The usual ecclesiastical and conventual fasts were largely increased and the daily food was bread and water ... They were also fanatical total abstainers; not only was St. Benedict's kindly concession of a hemina of wine rejected, but the vineyards were rooted up and the wine-presses and vessels destroyed ... Truly, relaxation was inevitable. It was never reasonable that the heroic austerities of St. Bernard and his companions should be made the rule, then and always, for every monk of the order ... It was always the custom for each one to dilute the wine given him.

- ^ 92.0 92.1

"Altar Wine" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia

"Altar Wine" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ 93.0 93.1 Ask the Wise Man: Eucharistic Wine and an Alcoholic Priest; Hosts for the Gluten-allergic. St. Anthony Messenger. May 1996 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-07-18).

- ^ Wine, Religion and Culture. Macedonian Heritage. 2003 [2007-02-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-13).

- ^ See West, Drinking and Mathison, "Protestant Transubstantiation" parts 2 and 3 for many examples.

- ^ Jim West. A Sober Assessment of Reformational Drinking. Modern Reformation. March /April 2000, 9 (2).

- ^ Article 7. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-09).

- ^ Article 18. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2017-08-08).

- ^ Belgic Confession (1561), article 35 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Heidelberg Catechism (1563), questions 78-80 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Thirty-Nine Articles (1571), article 28 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ Westminster Confession of Faith (1647), chapter 29, paragraph 3 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- ^ West, Drinking, pp. 68ff.

- ^ West, Drinking, pp. 79ff.

- ^ West, Drinking, p. 86.

- ^ Increase Mather (1673)."Wo to Drunkards."

- ^ John Wesley. On the Use of Money. Thomas Jackson (ed.) (編). The Sermons of John Wesley. Wesley Center for Applied Theology at Northwest Nazarene University. 1999 [1872] [2008-05-20]. (原始內容存檔於2008-05-30).

- ^ Methodist Episcopal Church. Directions given to the Band-Societies. December 25th, 1744.. Doctrines and Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church. with explanatory notes by Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury 10th. 1798: 150 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2013-06-07).

- ^ 109.0 109.1 Nathan Bangs. A History of the Methodist Episcopal Church 1. New York: T. Mason and G. Lane for the Methodist Episcopal Church. 1838: 134f.

- ^ Henry J. Fox and William B. Hoyt. Rule Respecting Intoxicating Liquors. Quadrennial Register of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Connecticut: Case, Tiffany & Co. 1852: 200f.

- ^ Coke and Asbury, notes on Article XIX (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館), p. 24.

- ^ John McClintock and James Strong (eds.). Temperance Reform. Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature X. New York: Harper and Brothers: 245f. 1891 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2013-05-30).

In January, 1826, Rev. Calvin Chapin published in the Connecticut Observer a series of articles in which he took the ground that the only real antidote for the evils deprecated is total abstinence, not only from distilled spirits, but from all intoxicating beverages. His position, however, was generally regarded as extreme, and he had few immediate converts to his opinions.

- ^ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Keith Mathison. Protestant Transubstantiation - Part 4: Origins of and Reasons for the Rejection of Wine. IIIM Magazine Online. January 22–28, 2001, 3 (4) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-03-18).

- ^ Ra McLaughlin. Protestant Transubstantiation (History of). Third Millennium Ministries. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-24).

- ^ Pierard, p. 28.

- ^ M. D. Coogan. Wine. Bruce Metzger and M. D. Coogan (編). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press, USA: 799f. 1993. ISBN 978-0-19-504645-8.

- ^ Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield. The Lord's Supper. American Methodist Worship. New York: Oxford University Press. 2001: 151. ISBN 0-19-512698-X.

- ^ Bacchiocchi, Samuele. The Preservation of Grape Juice. Wine in the Bible. Signal Press & Biblical Perspectives. 1989 [2013-03-05]. ISBN 1-930987-07-2. (原始內容存檔於2012-12-28).

- ^ Hallett, Anthony; Diane Hallett. Thomas B. Welch, Charles E. Welch. Entrepreneur Magazine Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurs. John Wiley and Sons: 481–483. 1997 [2013-03-05]. ISBN 0-471-17536-6. (原始內容存檔於2012-02-20).

- ^ W. Liese, J. Keating, and W. Shanley. Temperance Movements. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1912 [2008-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2017-12-07).

- ^ Prelate Assails Dry Law. Archbishop Messmer Forbids Catholic Help to Amendment (PDF). The New York Times. June 25, 1918: 13 [2008-05-20]. (原始內容存檔於2012-11-11).

- ^ McClintock and Strong, "Temperance Reform", p. 248: "[T]he [temperance] cause received a new impulse from the presence and labors of father Mathew, the Irish apostle of temperance, who came to America in June and spent sixteen months of hard work chiefly among the Irish Catholics. Crowds greeted him everywhere, and large numbers took the pledge at his hands. It is not surprising that a reaction followed this swift success. Many pledged themselves by a sudden impulse, moved thereto by the enthusiasm of assembled multitudes, with little, clear, intelligent, fixed conviction of the evils inseparable from the habits which they were renouncing. The pope, their infallible teacher both in regard to faith and morals, had never pronounced moderate drinking a sin, either mortal or venial; and even occasional drunkenness had been treated in the confessional as a trivial offence.... [T]he Catholic clergy, as a body, seem to have made no vigorous effort to hold the ground which the venerable father Matthew won; and the laity, of course, have felt no obligation be wiser than their teachers."

- ^ Ruth C. Engs. Protestants and Catholics: Drunken Barbarians and Mellow Romans?. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-05).

Wide scale temperance movements and anti-alcohol sentiments have not been, and are not, found in southern European Roman Catholic countries.... In hard-drinking eastern European Catholic countries, such as Russia and Poland, sporadic anti-drunk campaigns have been launched but have only been short lived. This has also been found in Ireland (Levine, 1992).

Adapted from Ruth C. Engs. What Should We Be Researching? - Past Influences, Future Ventures. Elini Houghton and Ann M. Roche (eds.) (編). Learning about Drinking. International Center for Alcohol Policies. 2001. - ^ Lilian Lewis Shiman. Crusade Against Drink in Victorian England. St. Martin's Press. 1988: 5. ISBN 0-312-17777-1.

- ^ John Kobler. Ardent Spirits: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. Da Capo Press. 1993: 53. ISBN 0-306-80512-X.

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Engs: "Levine has noted that 'in Western societies, only Nordic and English-speaking cultures developed large, ongoing, extremely popular temperance movements in the nineteenth century and the first third or so of the twentieth century.' He also observed that temperance – anti alcohol – cultures have been, and still are, Protestant societies."

- ^ Quoted in Williamson, p. 9.

- ^ Ken Camp. Drink to That? Have Baptists watered down their objections to alcohol?. The Baptist Standard. 2007-01-05 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2016-05-08).

- ^ McClintock and Strong, p. 249, lists Sweden, Australia, Madagascar, India, and China.

- ^ Patrick Madrid. Wrath of Grapes. This Rock. March 1992, 3 (3) [2007-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2007-03-07).

The [Catholic] Church teaches ... that wine, like food, sex, laughter, and dancing, is a good thing when enjoyed in its proper time and context. To abuse any good thing is a sin, but the thing abused does not itself become sinful.

- ^ Paul O'Callaghan. The Spirit of True Christianity. Word Magazine (Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America). March 1992: 8–9 [2007-03-16]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-16).

So alcohol, sex, the body, money, television, and music are all good things. It is only the abuse of these things that is bad—drunkenness, pornography, compulsive gambling, etc. Even drugs marijuana, cocaine, heroin—all have good uses for medical and other reasons. It’s only the abuse of them for pleasure that is wrong.

- ^ 132.0 132.1 Responding to Opportunities for 'Interim Eucharistic Sharing' (PDF). Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. [2007-02-24]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2007-02-14).

While many Lutheran congregations also provide grape juice or unfermented wine as an alternative, Lutherans have more emphasized the historical and ecumenical continuities which wine provides, as well as the richness and multivalences of its symbolic associations.

- ^ Theology and Practice of The Lord's Supper - Part I (PDF). Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod. May 1983 [2007-02-24]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2011-03-01).

- ^ Maintain a Balanced View Of Alcohol. Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. 2004 [2012-11-24]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-16).

- ^ Alcohol. Presbyterian 101. Presbyterian Church (USA). [2007-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2003-04-13).

- ^ 136.0 136.1 Introduction to Worship in the United Church of Christ (PDF). Book of Worship. United Church of Christ: Footnote 27. 1986 [2007-02-24]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2012-06-08).

- ^ 137.0 137.1 Alcohol. Christian Reformed Church in North America. 1996–2007 [2007-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2012-10-21).

- ^ Alcohol, Beverage use of. Presbyterian Church in America, 8th General Assembly. 1980 [2007-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2017-09-12).

- ^ Alcoholic Beverages. Orthodox Presbyterian Church. [2007-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2007-08-09).

- ^ Jeffrey J. Meyers. Concerning Wine and Beer, Part 1. Rite Reasons, Studies in Worship. November 1996, (48) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-03).

- ^ Jeffrey J. Meyers. Concerning Wine and Beer, Part 2. Rite Reasons, Studies in Worship. January 1997, (49) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2017-07-07).

- ^ Pierard, p. 29.

- ^ 143.0 143.1 Robert R. Gonzales, Jr. The Son of Man Came Drinking. RBS Tabletalk. Reformed Baptist Seminary. [2010-02-15]. (原始內容存檔於2012-12-28).

[E]ven if the wine Jesus drank had a lower alcohol context than today's wine, the issue is still moderation not abstinence. The believer may not be able to drink as many glasses of modern wine compared to ancient wine and remain within the bounds of moderation. Instead of drinking 20 glasses of ancient wine, we'd have to limit ourselves to 2 glasses of modern wine. But still, the issue is moderation, not abstinence.

- ^ Wine or grape juice. Orthodox Presbyterian Church. [2007-02-24]. (原始內容存檔於2007-08-09).

- ^ Cross and Livingstone, p. 1767.

- ^ M. R. P. McGuire and T. D. Terry (編). New Catholic Encyclopedia 14 2nd ed. Thomson Gale: 772. 2002. ISBN 978-0-7876-4004-0.

- ^ The Bible Speaks on Alcohol. The Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention. [2011-07-27]. (原始內容存檔於2011-07-22).

- ^ Position paper: Abstinence from Alcohol (PDF). Assemblies of God. [2009-08-18]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2010-02-15).

- ^ Alcohol and Other Drugs. The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church. The United Methodist Publishing House. 2004 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-06-02)..

- ^ 150.0 150.1 Salvation Army's Position Statements: Alcohol and Drugs. 1982 [2012-04-03].

The Salvation Army ... has historically required total abstinence of its soldiers and officers. While not condemning those outside its ranks who choose to indulge, it nevertheless believes total abstinence to be the only certain guarantee against overindulgence and the evils attendant on addiction.

[永久失效連結] - ^ Graham, Billy. My Answer. Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-26).

- ^ John F. MacArthur. Living in the Spirit: Be Not Drunk with Wine--Part 3. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-12).

- ^ R. Albert Mohler and Russell Moore. Alcohol and Ministry (MP3 audio). Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. 2005-09-14 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-10-08).

- ^ 154.0 154.1 John Piper. Total Abstinence and Church Membership. 1981-10-04 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2008-11-20).

- ^ For example, Stephen Arterburn and Jim Burns. Myths and Facts about Alcohol Consumption. 2007 [2007-11-19]. (原始內容存檔於2012-03-18).

For the general population, no specific Scriptures forbid wine consumption in small amounts ... In our society, with so much damage being done by drinking, many who think it is okay to drink need to reexamine the practice ... And for us parents who have to be concerned about the behaviors we are modeling, abstinence is the best choice.

- ^ 156.0 156.1 Daniel L. Akin. FIRST-PERSON: The case for alcohol abstinence. Baptist Press. 2006-06-30 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-03-23).

- ^ 157.0 157.1 Richard Land. FIRST-PERSON: The great alcohol debate. Baptist Press. 2006-07-24 [2007-07-25]. (原始內容存檔於2007-10-07).

- ^ John MacArthur. Unity in Action: Building Up One Another Without Offending--Part 2. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2007-02-02).

- ^ David Guzik. Commentary on 1 Ti 5:23. [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2006-12-08).

- ^ Kenneth L. Barker and John R. Kohlenberger III. Commentary on 1 Ti 5:23. Zondervan NIV Bible Commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan Pub. House. 1999. ISBN 978-0-310-57840-6.

- ^ 161.0 161.1 D. Miall Edwards. Drunkenness. James Orr (編). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. 1915 [2007-03-09]. (原始內容存檔於2007-09-27).

- ^ Norman Geisler. A Christian Perspective on Wine-Drinking. Bibliotheca Sacra. January–March 1982, 139 (553): 41–55.

- ^ W. J. Beecher. Total abstinence. The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge: 468. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2016-04-16).

- ^ Resolution On The Liquor Situation. Southern Baptist Convention. 1938 [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2012-03-19).

We declare afresh our unalterable opposition to the whole liquor traffic, whisky, beer, and wine, and to the license system by which this most blighting and corrupting traffic fastened upon our body social and body politic.... We stand unalterable for total abstinence on the part of the individual and for prohibition by the government, local, State, and National, and that we declare relentless war upon the liquor traffic, both legal and illegal, until it shall be banished.... [T]his Convention earnestly recommends to our Baptist people, both pastors and churches, that the churches take a firm and consistent stand against all indulgence in the use of intoxicating liquors, including wine and beer, and against all participation in their sale by members of the churches, and that we seek as rapidly as possible to educate our people against the folly and sin of such use and sale, and that as rapidly as possible our churches shall be relieved of the open shame and burden of church members in any way connected with the unholy traffic

- ^ On alcohol use in America. Southern Baptist Convention. 2006 [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2013-11-05).

RESOLVED ... total opposition to the manufacturing, advertising, distributing, and consuming of alcoholic beverages.

- ^ Historic Stand for Temperance Principles and Acceptance of Donations Statement Impacts Social Change. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 1992 [2007-02-28]. (原始內容存檔於2006年12月6日).

- ^ Chemical Use, Abuse, and Dependency. General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists. 1990 [2007-02-28]. (原始內容存檔於2006年12月6日).

- ^ William Booth. 27. Strong Drink. The Training of Children: How to Make the Children into Saints and Soldiers of Jesus Christ 2nd. 1888.

Make the children understand that the thing is an evil in itself. Show them that it is manufactured by man - that God never made a drop of alcohol. To say that alcohol is a good creature of God is one of the devil's own lies fathered on foolish and ignorant people. It is a man-manufactured article. The earth nowhere produces a drop of it. The good creatures of God have to be tortured and perverted before any of it can be obtained. There is not a drop in all creation made by God or that owes its existence to purely natural causes.... Make your children understand that it is not safe for them or anybody else to take strong drink in what is called moderation, and that even if it were, their example would be sure to induce others to take it, some of whom would be almost certain to go to excess.... Therefore, the only way of safety for your children as regards themselves and the answer of a good conscience with respect to others, is total abstinence from the evil.

- ^ Reynolds, The Biblical Approach to Alcohol.

- ^ Stephen M. Reynolds. Alcohol and the Bible. Challenge Press. 1983. ISBN 978-0-86645-094-2.

- ^ 171.0 171.1 171.2 Stephen M. Reynolds. Issue and Interchange - Scripture Prohibits the Drinking of Alhocolic Beverages. Antithesis. May /June 1991, 2 (2) [2007-01-22]. (原始內容存檔於2018-04-14). See also the other installments in the debate between Reynolds and Kenneth Gentry in the same issue of the magazine (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館).

- ^ Jack Van Impe. Alcohol: The Beloved Enemy. Jack Van Impe Ministries. 1980. ISBN 978-0-934803-07-6.

- ^ 1 Timothy 5:23. [2013-03-05]. (原始內容存檔於2012-11-02).

- ^ The Commandments: Obey the Word of Wisdom. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. [2007-06-29]. (原始內容存檔於2011-07-16).

- ^ Ezra Taft Benson. A Principle with a Promise. Ensign. May 1983: 53–55 [2007-06-29].

- ^ The Doctrine and Covenants, section 89: "That inasmuch as any man drinketh wine or strong drink among you, behold it is not good, neither meet in the sight of your Father, only in assembling yourselves together to offer up your sacraments before him. And, behold, this should be wine, yea, pure wine of the grape of the vine, of your own make [compare D&C 27:2-4]. And, again, strong drinks are not for the belly, but for the washing of your bodies."

- ^ Guide to the Scriptures: Sacrament. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2006 [2007-06-29]. (原始內容存檔於2010-10-14).