用戶:JAK/盒/69

足球裝備(又稱用品、制服,英語:kit、strip、uniform)是足球員在比賽時所穿着的基本裝備和服裝。球例(Laws of the Game)明確指明一位球員必須使用的用品,亦禁止球員或其他參與者使用有危險性的用品。個別的比賽會有更深入的限制,例如調整球衣上標誌的大小;明確規定一場比賽中,若兩隊的隊服有相似顏色或容易引起混淆,作客的球隊必須穿上其他制服。

足球員一般會穿上背面印有號碼的球衣進行比賽。原先一支球隊的球員必須穿上1至11號球衣,和他們司職的位置相對,在職業賽事裏球衣號碼則由球員名單編定,每位球員皆獲分配一個持續一個球季的固定號碼。職業足球會亦會在球衣背面印上球員的姓氏或暱稱,一般會印在號碼的上面。

足球運動起源不久,它的用品已經不斷發展,當時足球員會穿着厚綿球衣,燈籠褲和厚硬皮革球鞋。於12世紀球鞋的重量減低及變軟,球褲的長度縮短;製衣技術改良和印刷術使球褲可使用更輕盈的人造纖維製造,使色彩增強和容許較複雜的設計。贊助商的標誌亦出現在用品上,球隊亦會複製他們的裝備供球迷們購買,以賺取收入。

裝備

[編輯]基本裝備

[編輯]

球例於第四條規例球員裝備(The Players' Equipment)列明球員必須在比賽必須佩戴的裝備。它明確說明了五項物件,包括球衣、短褲、襪、鞋及護脛[1]。守門員則容許穿着長褲(tracksuit bottoms)來代替短褲[2]。大部分球員會穿着被稱為球靴的釘鞋,球例卻沒有列明必須穿着[1]。球衣必須帶有袖子,以使其他球員和官方代表分辦得更清楚。球員亦可穿着保暖內褲,但必須和球褲的顏色一樣。護脛需由橡膠、塑膠或相似物料所製造,且必須完全被襪子所遮蓋,以及「提供一個適當的保護程度」[1]。其它被球例規定所禁止的裝備,條件是一名球員「不可以使用一些裝備或佩戴任何物品會對自己或其他球員構成危險」[1]。

雖然球例只指明「兩隊必須穿上的球衣顏色,以作雙方、球證和旁證的識別」[1],但個別的比賽則規定一方的後備球員穿上相同顏色的衣服。在一場比賽當中,如雙方的球衣過於相似或會被混淆,作客球隊必須更換球衣的顏色[3]。因為這個規定,一支球隊的第二選擇球衣常被稱為「作客球衣」或「作客顏色」。但有些球隊在球衣沒有和對方撞色下,選擇穿著作客球衣,甚至有些球隊故意於主場穿著作客球衣。這情況不乏例子,特別是國家隊,英格蘭國家隊偶爾在非必要下穿着其作客紅色球衣作賽,他們更穿着這球衣贏得1966年世界盃[4]。很多職業足球隊亦有「第三球衣」或「第二作客球衣」,當球隊的首選和作客球衣的顏色亦和他們的對手相近下,便會使用這件球衣[5]。大部分職業足球隊皆沿用他們的球衣顏色很久[5],而球衣顏色本身就是球會一個重要的文化[6]。國家隊通常穿着「國家顏色」(national colours)比賽,和國家的其他體育項目代表隊一樣。國家顏色通常基於國旗的顏色,但有例外--意大利國家隊的藍色,是薩伏依王朝的代表顏色[7]。

球衣一般會以聚酯網製造,它不會吸收汗水和身體熱力,和以天然纖維製造的球衣一樣[8]。大部分職業球會會在球衣前方印有贊助商的標誌,象徵獲得的龐大收入[9],亦有一些球會讓贊助商的標誌印在球衣背面[10]。球例對標誌作出一些限制,例如標誌可以有多大或什麼標誌可以展示[11]。一些比賽如英超,要求球員在袖子戴補釘,以展示該賽事的標誌[12]。球員的號碼大多印在球衣的背面,而部分國家隊會印出球員的號碼於球衣的前方[13],職業球隊會印出球員的姓氏於號碼的上方[14]。球隊的隊長而要佩戴織入橡皮筋的臂章於左袖子,以示對球證和球迷的識別[15]。

現時大部分球員穿着比賽的專業球靴,多以皮革或人造物料製造。現代球靴被裁至略低於足踝,和從前使用的高踝鞋相反,並在鞋底繫上釘子。釘子可直接鑄造於鞋底,亦可自行繫上螺絲釘[16]。現代球靴如前FC利物浦名將莊士東(Craig Johnston)設計的Adidas Predator,特色是非常複雜、科學化的設計,例如在鞋底裝上空中氣渦和以橡膠刀片取代釘子[17]。一些大球會對刀片設計頗有微言,他們責備刀片容易令球員受傷,穿着者亦如是[18][19]。一些球員故意選擇較緊身的球靴比賽,他們認為這能加強控球能力,但這方法被批評會令球員較易受傷[20]。

其他裝備

[編輯]

所有球員都可戴手套[21],守門員則可戴守龍門專用的手套。1970年代前,手套使用率極低[22],但現在幾乎沒有可能看見一個沒有佩戴手套的守門員。在2004年歐洲國家盃八強葡萄牙隊對英格蘭隊,前者門將列卡度·彭利拿因在互射十二碼階段除去手套令球迷們議論紛紛[23]。從1980年代起,手套的設計有突破性的發展,以保護器防止手指被截斷、分割術增加彈性和手套的掌部使用特別物料設計,以保護手部和增強接抓球能力[22]。手套亦分為多種式樣,包括「平手掌」(flat palm)、「滾動手指」(roll finger)和「反式」(negative)等,視乎縫紉及合身度加以變化[24]。守門員有時會戴帽子以防止太陽光或燈光的照射影響表現[21]。視力有問題的球員會佩戴眼鏡,只要眼鏡不會脫離或爆裂發生危險便可佩戴。大部分球員選擇佩戴隱形眼鏡,除非患有眼疾,著名的例子是荷蘭球員戴維斯因患有青光眼而不能佩戴隱形眼鏡,而戴了一副特殊的護目鏡,它的鏡片伸展到頭兩邊[25]。其他有可能會對球員構成危險的物品(如珠寶首飾)則不允許佩戴[1]。其他會被球員穿着的用品,包括排汗層(base layers),例如Nike的NikePro系列和Canterbury的BaseLayer系列[26]。球員亦可選擇佩戴頭套以保護自己免受頭部的傷害,只要該頭盔沒有機會對其他球員構成任何危險,便可佩戴。[27]

官方裝備

[編輯]

球證、旁證和第四球證的裝備和球員的風格相近。雖然球例沒有列明,但球證所穿制服的顏色會約定俗成地和兩隊所穿球衣的顏色不同[28]。1998年,英超聯賽球證大衛·艾拿尼(David Elleray)曾在執法阿士東維拉對溫布頓的賽事中段被逼換掉制服,因為他的制服的顏色和溫布頓的球衣顏色太相近[29]。傳統黑色是代表官方人員的顏色,人們經常以「黑衣判官」這個非正式的術語來形容球證[30]。但在現代足球,球證亦會穿着其他顏色的制服[31]。儘管衣袖受到限制,球證的制服有時亦會印上贊助商的標誌[32]。

歷史

[編輯]初期發展

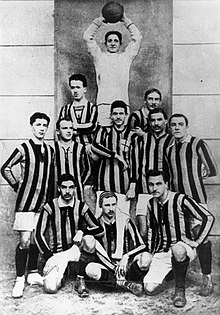

[編輯]在1860年代,英格蘭開始出現足球這項運動,但當時仍沒有對選擇球衣的標準。球隊可以穿上任何衣服,有一些球員以帽子或腰帶來分辨隊友[5]。這帶來了問題,一本1867年的足球冊子建議球隊應嘗試「在事前作出安排,一方穿上單色的間條球衣,如紅色;另一方則穿着其他顏色,如藍色。這能避免混亂和粗野地從你的隊友搶去皮球。」[33]

在1870年代,首套標準足球裝備推出,和學校與其他體育團體有密切關係的足球會,使用的裝備的設計和他們會有所影響[5]。例如布力般流浪的球衣一開二的設計沿於馬雲書院(Malvern College),隊中不少球員在這間書院畢業。而球隊最初使用的淺藍色和白色就為了顯示和劍橋大學的關係,因為幾位球會創立者曾在這家著名學府受教育。[34] Colours and designs often changed dramatically between matches, with Bolton Wanderers turning out in both pink shirts and white shirts with red spots within the same year.[35] Rather than the modern shorts, players wore long knickerbockers or full-length trousers, often with a belt or even braces.[36] Lord Kinnaird, an early star of the game, was noted for always being resplendent in long white trousers.[37] There were no numbers printed on shirts to identify individual players, and the programme for an 1875 match between Queen's Park and Wanderers in Glasgow identifies the players by the colours of their caps or stockings.[38] The first shin pads were worn in 1874 by the Nottingham Forest player Sam Weller Widdowson, who cut down a pair of cricket pads and wore them outside his stockings. Initially the concept was ridiculed but it soon caught on with other players.[39] By the turn of the century pads had become smaller and were being worn inside the stockings.[40]

As the game gradually moved away from being a pursuit for wealthy amateurs to one dominated by working-class professionals, kits changed accordingly. The clubs themselves, rather than individual players, were now responsible for purchasing kit and financial concerns, along with the need for the growing numbers of spectators to easily identify the players, led to the lurid colours of earlier years being abandoned in favour of simple combinations of primary colours. In 1890 the Football League, which had been formed two years earlier, ruled that no two member teams could have similar kits, so as to avoid clashes. This rule was later abandoned in favour of one stipulating that all teams must have a second set of shirts in a different colour available.[5] Initially the home team was required to change colours in the event of a clash, but in 1921 the rule was amended to require the away team to change.[41]

Specialised football boots began to emerge in the professional era, taking the place of everyday shoes or work boots. Players initially simply nailed strips of leather to their boots to enhance their grip, leading the Football Association to rule in 1863 that no nails could project from boots. By the 1880s these crude attachments had become studs. Boots of this era were made of heavy leather, had hard toecaps, and came high above a player's ankles.[42]

二十世紀初

[編輯]As the game began to spread to Europe and beyond, clubs adopted kits similar to those worn in the United Kingdom, and in some cases chose colours directly inspired by British clubs. In 1903, Juventus of Italy adopted a black and white kit inspired by Notts County.[43] Two years later, Argentina's Club Atlético Independiente adopted red shirts after watching Nottingham Forest play.[44]

In 1904 the Football Association dropped its rule that players' knickerbockers must cover their knees and teams began wearing them much shorter. They became known as "knickers", and were referred to by this term until the 1960s when "shorts" became the preferred term.[36] Initially, almost all teams wore knickers of a contrasting colour to their shirts.[5] In 1909, in a bid to assist referees in identifying the goalkeeper amongst a ruck of players, the Laws of the Game were amended to state that the goalkeeper must wear a shirt of a different colour to his team-mates. Initially it was specified that goalkeepers' shirts must be either scarlet or royal blue, but when green was added as a third option in 1912 it caught on the extent that soon almost every goalkeeper was playing in green. In this period goalkeepers generally wore a heavy woollen garment more akin to a jumper than the shirts worn by outfield players.[36]

Sporadic experiments with numbered shirts took place in the 1920s but the idea did not initially catch on.[45] The first major match in which numbers were worn was the 1933 FA Cup Final between Everton and Manchester City. Rather than the numbers being added to the clubs' existing kits, two special kits, one white and one red, were made for the final and allocated to the two teams by the toss of a coin. The Everton players wore numbers 1–11, while the City players wore 12–22.[46] It was not until around the time of the Second World War that numbering became standard, with teams wearing numbers 1–11. Although there were no regulations on which player should wear which number, specific numbers came to be associated with specific positions on the field of play, a prime example being the number 9 shirt which was usually reserved for the team's main striker.[45] The 1930s also saw great advancements in boot manufacture, with new synthetic materials and softer leathers becoming available. By 1936 players in Europe were wearing boots which weighed only a third of the weight of the rigid boots of a decade earlier, although British clubs did not adopt the new-style boots, with players such as Billy Wright openly pronouncing their disdain for the new footwear and claiming that it was more suited to ballet than football.[47]

In the period immediately after the war, many teams in Europe were forced to wear unusual kits due to clothing restrictions.[5] England's Oldham Athletic, who had traditionally worn blue and white, spent two seasons playing in red and white shirts borrowed from a local rugby league club,[48] and Scotland's Clyde wore khaki.[49] In the 1950s kits worn by players in southern Europe and South America became much more lightweight, with V-necks replacing collars on shirts and synthetic fabrics replacing heavy natural fibres.[21] The first boots to be cut below the ankle rather than high-topped were introduced by Adidas in 1954. Although they cost twice as much as existing styles the boots were a huge success and cemented the German company's place in the football market. Around the same time Adidas also developed the first boots with screw-in studs which could be changed according to pitch conditions.[16] Other areas were slower to adopt the new styles – British clubs once again resisted change and stuck resolutely to kits little different to those worn before the war,[21] and Eastern European teams continued to wear kits that were deemed old-fashioned elsewhere. The FC Dynamo Moscow team that toured Western Europe in 1945 drew almost as much comment for the players' long baggy shorts as for the quality of their football.[50] With the advent of international competitions such as the European Cup, the southern European style spread to the rest of the continent and by the end of the decade the heavy kits and boots of the pre-war years had fallen entirely out of use. The 1960s saw little innovation in kit design, with clubs generally opting for simple kits which looked good under the newly-adopted floodlights.[5] Kit designs from the late 1960s and early 1970s are highly regarded by football fans.[51]

現代發展

[編輯]

在1970年代,球會開始設計具強烈獨特射格的球衣 and in 1975 Leeds United, who had changed their traditional blue and gold kit to all white in the 1960s to mimic Real Madrid,[52] became the first club to design a kit which could be sold to fans in the form of replica shirts. Driven by commercial concerns, other clubs soon followed suit, adding manufacturers' logos and a higher level of trim.[5] The early part of the decade also saw the first sponsored kits, with top clubs such as Bayern Munich displaying companies' names on their shirts.[5] Soon almost all major clubs had signed such deals, although two top Spanish clubs, FC Barcelona and Athletic Bilbao, refused to allow sponsors' logos to appear on their shirts as recently as 2005.[53] Even today, Barcelona has refused paying sponsors in favor of wearing the UNICEF logo on their kits while donating €1.5 million to the charity per year.[54] Players also began to sign sponsorship deals with individual companies. In 1974 Johan Cruijff refused to wear the Dutch national team's kit as its Adidas branding conflicted with his own individual contract with Puma, and was permitted to wear a version without the Adidas branding.[55] Puma had also paid Pelé $120,000 to wear their boots and specifically requested that he bend down and tie his laces at the start of the 1970 FIFA World Cup final, ensuring a close-up of the boots for a worldwide television audience.[56]

In the 1980s manufacturers such as Hummel and Adidas began to design shirts with increasingly intricate designs, as new technology led to the introduction of such design elements as shadow prints and pinstripes.[5] Hummel's distinctive halved kit designed for the Danish national team for the 1986 FIFA World Cup caused a stir in the media but concern was raised by FIFA over its appearance on television.[57] Shorts became shorter than ever during the 1970s and 80s,[45] and often included the player's number on the front.[58] In the 1991 FA Cup Final Tottenham Hotspur's players lined up in long baggy shorts. At the time the new look was derided, but within a short period of time clubs both in Britain and elsewhere had adopted the longer shorts.[59] In the 1990s shirt designs became increasingly complex, with many teams sporting extremely gaudy kits. Design decisions were increasingly driven by the need for the shirt to look good when worn by fans as a fashion item,[5] but many designs from this era have since come to be regarded as amongst the worst of all time.[60] In 1996, Manchester United notoriously introduced a grey kit which had been specifically designed to look good when worn with jeans, but abandoned it halfway through a match after manager Alex Ferguson claimed that the reason why his team was losing 3–0 was that the players could not see each other on the pitch. United switched to a different kit for the second half and scored one goal without reply.[61] The leading leagues also introduced squad numbers, whereby each player is allocated a specific number for the duration of a season.[62] A brief fad arose for players celebrating goals by lifting or completely removing their shirts to reveal political, religious or personal slogans printed on undershirts. This led to a ruling from the International Football Association Board in 2002 that undershirts must not contain slogans or logos.[63]

The market for replica shirts has grown enormously, with the revenue generated for leading clubs and the frequency with which they change kit designs coming under increased scrutiny, especially in the United Kingdom, where the market for replicas is worth in excess of £200m.[64] Several clubs have been accused of price fixing, and in 2003 Manchester United were fined £1.65m by the Office of Fair Trading.[65] The high prices charged for replicas have also led to many fans buying fake shirts which are imported from countries such as Thailand and Malaysia.[66] Nonetheless, the chance for fans to purchase a shirt bearing the name and number of a star player can lead to significant revenue for a club. In the first six months after David Beckham's transfer to Real Madrid the club sold more than one million shirts bearing his name.[67] A market has also developed for shirts worn by players during significant matches, which are sold as collector's items. The shirt worn by Pelé in the 1970 FIFA World Cup Final sold at auction for over £150,000 in 2002.[68]

A number of advances in kit design have taken place since 2000, with varying degrees of success. In 2002 the Cameroon national team competed in the African Cup of Nations in Mali wearing shirts with no sleeves,[69] but FIFA later ruled that such garments were not considered to be shirts and therefore were not permitted under the Laws of the Game.[70] Manufacturers Puma AG initially added "invisible" black sleeves in order to comply with the ruling, but later supplied the team with a new one-piece singlet-style kit.[61] FIFA ordered the team not to wear the kit but the ruling was disregarded, with the result that the Cameroon team was deducted six points in its qualifying campaign for the 2006 FIFA World Cup,[71] a decision later reversed after an appeal.[72] More successful were the skin-tight shirts designed for the Italian national team by manufacturers Kappa, a style subsequently emulated by other national teams and club sides.[61]

參考資料

[編輯]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Law 4 — The Players' Equipment. Laws of the Game 2008/2009 (PDF). FIFA. : 18–19 [2008-09-01].

- ^ Interpretation of the laws of the game and guidelines for referees: Law 4 — The Players' Equipment. Laws of the Game 2008/2009 (PDF). FIFA. : 63–64.

- ^ Standardised League Rules. Wessex Football League. [2008-01-16].

- ^ Glen Isherwood; et al. England's Uniforms - Player Kits. England Football Online. [2008-01-23].

England sometimes choose to wear their red at home even though they could wear their white, as against Germany in the last match played at Wembley Stadium. The Football Association wished to invoke the spirit of 1966, when, in their finest moment at Wembley, England beat West Germany in the World Cup final wearing their red shirts.

- ^ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 David Moor. A Brief History of Football Kit Design in England and Scotland. HistoricalFootballKits.co.uk. [2008-01-14].

- ^ Giulianotti, Richard; Norman Bonney, Mike Hepworth. Football, Violence and Social Identity. Routledge. 1994: 75. ISBN 0-4150-9838-6.

For a supporter, whether or not he lives in the city of the team, the team colours are the most important symbol of his football faith, dominating any other symbol or cultural meaning such as nation, class or political party.

- ^ What's in a name? Part II. FIFA. 2000-02-05 [2008-09-01].

- ^ Football and health. BUPA. [2008-01-17].

- ^ Man Utd sign £56m AIG shirt deal. BBC. 2006-04-06 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Back-of-the-shirt Sponsors Draw. Notts County F.C. 2007-12-30 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Regulations Relating to Advertising on the Clothing of Players, Club Officials and match Officials (PDF). The FA. [2008-01-16].

- ^ The F.A. Premier League. Chris Kay International. [2008-01-22].

- ^ Q & A 2006. England Football Online. 2006-11-22 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. Cassell Illustrated. 2003: 158. ISBN 1-8440-3261-2.

- ^ Captain's armband is compulsory in PFF competitions : Faisal. FootballPakistan.com. 2007-12-05 [2008-01-22].

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Reilly, Thomas; A.M. Williams. Science and Soccer. Routledge. 2003: 125. ISBN 0-4152-6232-1.

- ^ Mike Adamson. Adidas Predator Absolute. The Guardian. 2006-01-13 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Ferguson wants bladed boots ban. BBC. 2005-09-24 [2008-01-18].

- ^ Warnock is concerned over blades. BBC. 2005-08-19 [2008-01-18].

- ^ Trevor D Prior. Why Do Footballers Keep Breaking Their Metatarsal Bones?. The Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists. [2008-01-18].

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Cox, Richard; Dave Russell, Wray Vamplew. Encyclopedia of British Football. Routledge. 2002: 75. ISBN 0-7146-5249-0.

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Football and Technology: Goalkeeper kit. Deutsches Patent- und Markenamt. [2008-01-15].

- ^ Craig Brown. Football: Euro 2004: Referee's error denies England victory. The Independent. 2004-06-25 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Goalkeeper Glove Cut Guide. TheGloveBag.com. 2006-03-28 [2008-07-14].

- ^ Goggles are Davids' most glaring feature. Soccertimes.com. 2003-03-07 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Base Layers. Pro Direct Soccer. [2008-01-17].

- ^ Cech's rugby-style headgear passes the FA's safety test. The Independent. 2007-01-20 [2008-04-16].

- ^ Advice for Newly Qualified Referees (PDF). The FA. [2008-01-15]. (PDF文件)

- ^ Jon Culley. Football: Merson revels in the Villa high life. The Independent. 1998-09-13 [2008-01-23].

- ^ Phil Shaw. Dowd sees the light as the man in black. The Independent. 2001-08-16 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Cox, Richard; Dave Russell, Wray Vamplew. Encyclopedia of British Football. Routledge. 2002: 76. ISBN 0-7146-5249-0.

- ^ Paul Kelso. Bright sparks hope over Burns reform. The Guardian. 2006-08-17 [2008-01-18].

A (relatively) affordable route into the Premiership has opened up for sponsors after the airline Emirates decided that this season will be its last as the official partner of top-flight referees....The successor will get exposure - its logo on the whistlers' shirt sleeves will be seen in 204 countries....

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 48.

- ^ 1875–1884: The early years. Blackburn Rovers F.C. 2007-07-02 [2008-01-14].

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football. : 48–49.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 51.

- ^ Will Bennett. Second FA Cup could fetch record £300,000 at auction. The Daily Telegraph. 2005-01-07 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Soar, Phil; Martin Tyler. The Game in Scotland. Encyclopedia of British Football. Willow Books. 1983: 65. ISBN 0-0021-8049-9.

- ^ Hucknall Cricketers. Ashfield District Council. [2008-01-15].

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 57.

- ^ Cox, Richard; Dave Russell, Wray Vamplew. Encyclopedia of British Football. Routledge. 2002: 74. ISBN 0-7146-5249-0.

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 3. Equipment: Bring on the Balls. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 55–56.

- ^ Black & White. Notts County F.C. 2007-05-21 [2008-01-15].

- ^ (西班牙文) Década del '10. Club Atlético Independiente. [2008-01-15].

- ^ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Davies, Hunter. Chapter 12. Equipment. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 156.

- ^ English FA Cup Finalists 1930 – 1939. HistoricalFootballKits.co.uk. [2008-01-15].

- ^ Davies, Hunter. Chapter 12. Equipment. Boots, Balls and Haircuts: An Illustrated History of Football from Then to Now. : 154–155.

- ^ Oldham Athletic. HistoricalKits.co.uk. [2008-01-17].

- ^ Clyde. HistoricalKits.co.uk. [2008-01-17].

- ^ Bob Crampsey. An historic day in Glasgow. BBC. 2001-10-16 [2008-01-15].

It's only a slight exaggeration to say that the Dynamo side looked like they came from Mars - they wore very dark blue tops and extremely baggy shorts with a blue band round the bottom.

- ^ Nick Szczepanik. The top 50 football kits. The Times. 2007-09-26 [2008-01-17].

- ^ Ball, Phil. Morbo: The Story of Spanish Football. WSC Books Ltd. 2003: 113. ISBN 0-9540-1345-8 請檢查

|isbn=值 (幫助).Indeed, when Don Revie took over at Leeds in the early 1960s he changed their kit from blue and gold to all white, modelling his new charges on the Spanish giants.

- ^ Barcelona eyes Beijing shirt deal. BBC. 2005-05-06 [2008-01-24].

- ^ Futbol Club Barcelona, UNICEF team up for children in global partnership. UNICEF. [2008-08-26].

- ^ Bruce Caldow. Don't mention the boot war. The Journal. [2008-01-24].

- ^ Erik Kirschbaum. How Adidas and Puma were born. The Journal. 2005-11-08 [2008-01-24].

- ^ Milestones: 1986. hummel International. [2008-01-16].

- ^ Isherwood, Glen. Admiral Mysteries. England Football Online. 6 June 2005 [2008-01-28].

- ^ English FA Cup Finalists 1990 – 1999. HistoricalFootballKits.co.uk. [2008-01-15].

- ^ Tom Fordyce. The worst football kits of all time. BBC. 2003-04-29 [2008-01-14].

- ^ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Dominic Raynor. 10 of the worst...football kits. ESPN. 2005-07-12 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Rob Smyth and Paolo Bandini. What's in a number?. The Guardian. 2006-09-06 [2008-01-16].

- ^ Stuart Roach. Henry gets the message. BBC. 2002-09-11 [2008-01-24].

- ^ Clubs rapped over kit sales. BBC. 1999-08-06 [2008-01-14].

The cost of replica kit - and the number of times new versions come on the market - has long been a bone of contention for football fans.

- ^ Man Utd fined for price fixing. BBC. 2003-08-01 [2008-01-14].

- ^ Darragh MacIntyre. The Fake Football Shirt Sting. BBC. 2006-03-03 [2008-01-14].

- ^ Beckham sells 250,000 Galaxy shirts before he gets to LA. Reuters UK. 2007-07-12 [2008-01-14].

- ^ Record price for Pele's shirt. BBC. 2002-03-22 [2008-01-17].

- ^ Indomitable fashions. BBC. 2002-01-22 [2008-01-14].

- ^ Fifa bans Cameroon shirts. BBC. 2002-03-09 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Cameroon docked six World Cup points for controversial kit. ABC News Australia. 2004-04-17 [2008-01-15].

- ^ Osasu Obayiuwana. Fifa lifts Cameroon sanction. BBC. 2004-05-21 [2008-01-15].