波兰境内的犹太人大屠杀

| |

| 概况 | |

|---|---|

| 时间 | 1939年9月-1945年4月 |

| 地点 | 德占波兰,以及今日的西乌克兰、西白俄罗斯等地 |

| 主要实施者 | |

| 部队 | 骷髅总队、别动队、秩序警察、特拉夫尼基人、白俄罗斯国土防卫军、乌克兰反抗军、立陶宛TDA营、立陶宛特别支队[1][2][3] |

| 受害者 | 300万波兰犹太人[4];学界对300万波兰人遇难者是否属于犹太人大屠杀受害者存在争议[5] |

| 幸存者 | 5万-12万人;[6]一说21万-23万人;[7]一说总计35万人。[8] |

| 武装抵抗 | |

| 隔都与集中营起义 | 本津、比亚韦斯托克、比克瑙、琴斯托霍瓦、拉赫瓦、卢茨克、马佐夫舍地区明斯克、米佐什、平斯克、波尼亚托瓦、索比布尔、索斯诺维耶茨、特雷布林卡、华沙、维尔纽斯 |

波兰境内的犹太人大屠杀是纳粹德国在波兰占领区内实施的种族灭绝行动,以专门建造的灭绝营为特征。第二次世界大战期间,第三帝国的犹太人大屠杀夺走了300万波兰犹太人的生命,[4]占大屠杀中全部犹太人遇难者的半数。在德国的灭绝行动中,另有多达300万的波兰裔受害者,但学者们对于是否将他们同样归于犹太人大屠杀受害者仍有争议。[5] 纳粹系统性杀害了超过90%的波兰犹太人人口,德国建立的灭绝营在其中起到了核心作用。[9]

德国繁复的官僚机构的每个部门都参与了杀戮过程,从内政部、财政部到德国企业与国营铁路。[10][11]德国公司竞标合同,在波兰总督府和其他地区的集中营中建造焚尸炉。[9][12]

在德国占领期间,即使会让自己和家人付出最为高昂的代价,仍有许多波兰人成功地从德国人手中救下了犹太人。 在大屠杀期间救援犹太人的各国援救者中,波兰籍援救者的人数是最多的。[6][13]以色列已认定了6,992名波兰国际义人。[14]

只有一小部分波兰犹太人在德占波兰境内幸存下来。有一些向东逃出德国人的占领范围,进入1939年时被苏联吞并的波兰领土,[15]却和多达100万人的波兰非犹太公民一同被发配到西伯利亚强制劳役。[16][17]

背景

[编辑]在波兰沦陷前,波兰第二共和国政府就曾经对境内的犹太人进行屠杀和驱逐,而到了1939年入侵波兰之后,根据《莫洛托夫-里宾特洛甫条约》的秘密议定书,[18]纳粹德国和苏联将波兰划分为各自的占领区。波兰西部的大片地区被德国吞并。[19]苏联试图欺骗波兰人,使波兰人相信红军进入波兰东部是为了共同打击德国;[20]随后占领了战前波兰约52%的领土。在恐惧的气氛下,内务人民委员部和红军安排了一场做样子的公投(有争议),[21][22]苏联随即吞并了整个波兰前东部领土地区。苏联吞并的地区居住着1320至1370万人,[19][23]包括大量的乌克兰族和白俄罗斯族,以及130万犹太人。几个月之内,东部波兰犹太人与幸存的波兰人一起被安置到苏联内地深处。约有20-23万名波兰犹太人男性、女性和儿童被苏联安排离境。[24][25]

随着1941年6月22日德国军队入侵苏联占领区,两国早些时候在莫斯科签署的互不侵犯条约被撕毁。1941年到1943年间,波兰全境处于德国的控制之下。[26] 纳粹在波兰中部和东南部建立了半殖民地性质的波兰总督府,面积占原波兰领土的39%.[27]

纳粹的隔都化政策

[编辑]在第二次世界大战之前,波兰有350万犹太人,[8]主要居住在城市中;犹太人口约占波兰总人口的10%. 波兰犹太人历史博物馆的数据库提供了全国1,926个犹太社区的信息。[28]德国在征服波兰和1939年屠杀知识分子之后,[29]德国的第一项反犹太措施涉及将犹太人驱逐出第三帝国吞并领土的政策。[30]位于最西部的省份大波兰和东波美拉尼亚变成了全新的德国帝国大区,即但泽-西普鲁士帝国大区与瓦尔特兰帝国大区,[31]旨在是通过移居者殖民(“生存空间”)实现完全德国化。[32]罗兹市直接附属于新的Warthegau地区,吸收了大约4万名自周围地区驱逐出来的波兰犹太人。[33]共有20.4万名犹太人经过罗兹隔都。依照最初的计划,他们将被驱逐到波兰总督府;[34][35]然而大规模移除犹太人的最终目的地迟迟不决,直到两年后最终解决方案启动为止。[36]

德国占领当局在入侵后立即开始迫害波兰犹太人,特别是在主要城市地区。在头一年半的时间里,纳粹仅仅是剥夺犹太人的贵重物品和财产以获取利润,[9]将他们赶入临时的隔都,并迫使他们为公共工程和战争经济从事奴隶劳动。[38]在此期间,德国人命令犹太社区任命犹太人委员会管理隔都,从而“以最严格的方式”负责执行命令。[39]大多数隔都都建立在犹太人生活井井有条的城镇。出于后勤原因,没有铁路连接的德占区定居点中的犹太人社区被解散。[40]在一项涉及使用货运列车的大规模驱逐行动中,全体波兰犹太人被集中在与现有铁路走廊相邻的破败街区(Jüdischer Wohnbezirk),与其他社区隔离开来。[41]粮食供给完全取决于党卫队。[42]最初,犹太人被法律禁止烘焙面包; [43]纳粹以不可持续的方式将犹太人与公众隔绝。[42]

华沙隔都包含的犹太人比全法国都多;罗兹隔都的犹太人比荷兰的所有犹太人都多。居住在克拉科夫市的犹太人人数超过了整个意大利,而几乎每个波兰中等城镇的犹太人口都超过了全斯堪的纳维亚半岛的数目。整个欧洲东南部——匈牙利、罗马尼亚、保加利亚、南斯拉夫和希腊——的犹太人人数比波兰总督府最初的四个区还要少。[44]

在饱受战争蹂躏的波兰,犹太人口的萎缩可以按照隔都的存在划分为不同阶段。在隔都成立之前,[45]犹太人逃避迫害不会涉及法外的死刑处罚。[46]一旦隔都与外界隔绝,饥饿和疾病导致的死亡变得猖獗。走私食品和药品是唯一的缓解方法,林格布鲁姆称之为“两个民族间历史上最精彩的一页”。[46]在华沙,隔都消耗的食物中有高达80%是非法带入的。德国人推出的食品券提供了生存所需卡路里的9%.[47]在1940年11月至1943年5月的两年半时间里,约有10万犹太人在华沙隔都死于饥饿和疾病;1940年5月至1944年8月之间的四年多时间里,罗兹隔都大约有4万人死于类似原因。[47]到1941年底,隔都的大多数犹太人没有任何储蓄来支付党卫队进一步提供的散装食物的费用。[47]德国当局中的“生产主义者”试图通过将隔都变成企业来使其自我维持,他们的意见仅在德国袭击波兰东部的苏联占领区(即巴巴罗萨行动)之后才压过“消耗主义者”。[48]最主要的隔都通过生产东部前线所需的货物得到稳定[42],犹太人口的死亡率开始下降(至少是暂时的)。[48]

大规模枪决

[编辑]

随着1941年6月德国袭击苏联,希姆莱召集了一支约11,000人的部队,首次实施了一项消灭犹太人的计划。[49]巴巴罗萨行动期间,党卫队还从苏联国民中招募了协作者辅助警察。[1][50]当地的辅警为德国提供了人力,以及有关本地语言和地方的关键知识。[51]在后来所谓的“子弹大屠杀”中,在乌克兰和立陶宛的辅助人员的援助下,德国警察营(Orpo)、安全警察(SiPo)、武装党卫队与特殊别动队在前线后方执行独立于军队的任务,系统地枪决数万男女老幼。[52]

波兰东部地区(原苏占区)中有超过30个地点发生了屠杀事件,[53],包括布列斯特、塔尔诺波尔与比亚韦斯托克隔都等地,以及战前的省会城市卢茨克、利沃夫、斯坦尼斯瓦乌夫及维尔纽斯(参见博纳利大屠杀)[54]大规模杀戮行动的幸存者被关押在新的用于剥削的隔都,[27]并且在德国当局的心血来潮下因人为饥荒而慢慢饿死。[55]出于卫生考虑,成千上万因饥饿和虐待而死的人的尸体被埋葬在乱葬坑中。[56]1941年11月起,毒气车投入使用。[57]截至12月,波兰东半部和苏联最西部的共和国共有439,800名犹太人被杀害。东部反对“犹太人种族”的“毁灭性战争”政策已成为各阶层德国人的常识。[58]在两年的时间里,东部的枪杀受害者总数已增加到61.8万至80万犹太人。[59][60]在纳粹行刑队向柏林的报告中,苏德边境后方的所有地区已经实现了“去犹太化”。[61]

最终解决方案与隔都清场

[编辑]

1942年1月20日,在柏林附近举行的的万湖会议期间,波兰总督府国务秘书约瑟夫·布勒敦促莱因哈德·海德里希尽快开始实施计划中的“犹太人问题的最终解决方案”。[62]当时瓦尔特兰的海乌姆诺灭绝营已经以“重新安置”作为幌子,在几周的时间里尝试了以排放废气实现工业化杀戮的实验。[63]被选中的隔都囚犯无一例外地被告知他们要去劳改营,并被要求随身携带行李。[64]许多犹太人相信了纳粹“转移营地”的说辞,因为驱逐也是隔都化过程的一部分。[6]另一方面,自1941年9月以来,卢布林区内一直在讨论通过固定毒气室实现大规模屠杀的想法。毒气室是新起草的莱茵哈德行动的先决条件。莱茵哈德行动的领导人由奥迪洛·格洛博奇尼克担任:他曾下令在贝乌热茨、索比布尔与特雷布林卡建造灭绝营。[65]在马伊达内克和奥斯威辛,固定毒气室的建设工作分别于3月和5月开始,使用齐克隆B的实验随即展开。[65]1942年至1944年间是大屠杀最极端的时期,来自波兰和欧洲其它地方的数百万犹太人在六座灭绝营中遇害。尽管这些集中营有时被错误地称作“波兰死亡营”,但莱因哈德行动中的所有集中营从来没有波兰警卫。所有杀戮中心都是由纳粹分子在严格保密下设计和运营的,并得到了乌克兰特拉夫尼基人的帮助。[66]平民被禁止接近这些杀人设施;如果有平民在集中营铁路附近被发现,他们往往会被枪杀。[67]

1942年初春,波兰总督府开始对境内的所有隔都实施系统清场,此时犹太人唯一的生存机会是逃到“雅利安地带”。德国人为所谓的“安置列车”实施围捕;几乎同一时期,德国的各大工程企业(包括HAHB、[68]埃尔福特的Topf and Sons、以及C.H. Kori GmbH等)为党卫队建造了灭绝设施,其建立与围捕行动直接相关。[69][70][71]

在其他纳粹集中营中,来自欧洲各地的囚犯被剥削用于德国的战争投入;而德国灭绝营是秘密的莱茵哈德行动的一部分,专门用于迅速消灭波兰和外国犹太人,在偏远的地点选址建造。身在柏林的海因里希·希姆莱掌控灭绝计划,但他将波兰地区的工作委托给了卢布林保留区的党卫队与警察司令奥迪洛·格洛博奇尼克;灭绝营的德国监督对希姆莱负责。[72]营地选址、设施建设和人员培训基于一项类似的“种族优生”计划——T-4行动。该计划在德国开发,是一项通过非自愿安乐死实现大规模屠杀的行动。[73][74]

“重新安置”项目

[编辑]倘若没有德意志国铁路,纳粹德国不可能实现如此规模的最终解决方案。[75]对波兰和外国犹太人的灭绝行动必须依赖铁路和僻静的杀戮中心。大屠杀列车加大了灭绝的规模,加快了灭绝所需的时间;此外,货运列车的封闭性也减少了护卫所需的部队人数。铁路运输使纳粹德国人能够建造和运营更大、更高效的灭绝营,同时向全世界世界——乃至纳粹的受害者——公开伪造一项“重新安置”计划。[10][76]在一次电话交谈中,海因里希·希姆莱告知马丁·鲍曼波兰的犹太人已被消灭,鲍曼博尔曼在回答时尖叫道:“他们没有被消灭,只是疏散,疏散,疏散!”[77]

莱因哈德行动期间,相当数量的被驱逐者因窒息和口渴在运送途中死亡,具体数量未知;运输途中没有提供食物或水。棚车(Güterwagen)只配有简单的茅厕。一个被栅栏封住的小窗户提供极少的通风,往往导致多人窒息而死。[78]一位特雷布林卡起义的幸存者证实了一辆这样的火车自比亚瓦-波德拉斯卡出发。当密封的门打开时,车上总计约6,000名犹太囚犯中有90%因窒息致死。他们的尸体被扔进称作“传染病院”(Lazaret)的阴燃万人坑。[79]数百万人在德国交通运输部的指导下,以类似的列车运送到灭绝营,并由IBM的一家子公司跟踪,直到1944年12月奥斯威辛-比克瑙集中营综合体正式关闭为止。[80][81]

死亡工厂只是众多大规模灭绝方式中的一种。纳粹在波兰东部设有僻静的杀戮地点:有5万名犹太人自布热西奇、别廖扎、亚努夫、科布林、霍洛德茨、安托帕利等隔都以及东方总督辖区西部边界上的其它地点运往布隆纳山,并在该地的行刑坑中处决;爆炸物被用来加速行刑坑的挖掘过程。[82][83][84]在前沃伦省的罗夫诺郊区的索森斯基森林中,有超过23,000名犹太人男女老幼被枪杀。[85]在波翁卡村(Górka Połonka)的森林(见地图),25,000名犹太人被迫脱光衣服,然后躺在其他人的尸体上被成批处决;其中大多数受害者来自卢茨克隔都。[86][87]利沃夫隔都囚犯的处决地点安排在亚诺夫斯卡附近,有35,000-40,000名犹太人被杀害后埋葬在皮亚斯基(Piaski)峡谷。[88]

秩序警察对占领区的犹太隔都实施了清场,将囚犯装入屠杀列车,并射杀无法转移或企图逃离的人。协同辅助警察通过在隔都实施大规模屠杀的方式,对犹太人民施加恐怖。[89][90]他们被部署在莱因哈德行动的所有主要杀戮地点:施加恐怖是党卫队训练他们的主要目的。[91]来自乌克兰的特拉夫尼基人部队在贝乌热茨、索比布尔、特雷布林卡二号营的犹太人灭绝行动中行动活跃;他们还在华沙(三次参与,见施特鲁普报告)、琴斯托霍瓦、卢布林、利沃夫、拉多姆、克拉科夫、比亚韦斯托克(两次)、马伊达内克、奥斯维辛、特拉夫尼基、[1]沃玛茨、缅济热茨、武库夫、拉曾、帕尔切夫、孔斯科沃拉、科马鲁夫卡等地,以及卢布林/马伊达内克集中营的其余分区(包括波尼亚托瓦、克拉希尼克、普瓦维)实施大屠杀。特拉夫尼基人的行动得到了党卫队、党卫队保安处、刑事警察以及秩序警察后备警察营的支援(每支部队都对数千名犹太人的消灭负责)。[92]犹太人的大规模处决(如在舍布涅的情况)是党卫队海德拉格训练场[93]的乌克兰武装党卫队师士兵常规训练的一部分。[94][95]在东北部,奥斯卡·迪尔勒万格的“偷猎者旅”在白俄罗斯辅警的帮助下,在杀戮行动中训练白俄罗斯国土卫队。[96]截至1945年5月第二次世界大战欧洲战场结束时,已有超过90%的波兰犹太人丧生。[6]

海乌姆诺灭绝营

[编辑]

海乌姆诺灭绝营建于希特勒发动巴巴罗萨行动之后,是纳粹建造的第一座灭绝营。该集中营是开发其他灭绝场所的试点项目。纳粹先前在索尔达乌以毒气杀害了1,500名波兰人,完成了以毒气处决的相关实验。[97]海乌姆诺的杀戮方法源于“安乐死”计划;该计划中,大量不知情的医院病人在伯恩堡、哈达玛尔与索能斯坦的气密淋浴房中被毒气杀死。[98]距罗兹50公里的海乌姆诺的杀戮场地包括一处类似于索能斯坦的被腾退的庄园,用于脱衣,其后面有卡车装载坡道。海乌姆诺西北4公里处有一处大型森林空地,被用于大规模埋葬以及一段时间后引入的露天火化。[99]

所有来自瓦尔特兰帝国大区的去犹太化区域的犹太人都被以“重新安置”的名义发配到海乌姆诺。至少有14.5万名来自罗兹隔都的囚犯在1942年至1944年间的几次驱逐行动中丧生于海乌姆诺。[100][101]此外,还有2万名外国犹太人和5,000名罗姆人从德国、奥地利和捷克斯洛伐克被带入。[102]所有受害者都被移动式毒气车(Sonderwagen)杀死:车上的排气管经过重新配置,汽油中添加毒药。在灭绝营存在的最后阶段,尸体被挖掘出来并在1005特别行动期间露天火化了几周。骨灰与碎骨混合在一起,装在用床单制成的口袋中,每晚用卡车运倒入附近的瓦尔塔河,从而去除大屠杀的证据。[103][104]

奥斯维辛-比克瑙

[编辑]

奥斯威辛集中营是德国纳粹建造的最大的灭绝中心,位于克拉科夫以西64公里处。[105]奥斯威辛平均每天处理1.5列大屠杀列车。[77]绝大多数被遣送至奥斯维辛的囚犯在抵达后数小时内便被杀害。[106]集中营于1942年3月安装了第一个永久性毒气室。使用齐克隆B为杀人毒剂的犹太人灭绝于7月开始。[107]1943年,纳粹在比克瑙建造了四组杀戮装置,每组装置包括更衣室、多个毒气室和工业规模的焚尸炉)。[108]到1943年底,比克瑙这座杀戮工厂已经拥有了四座所谓的“碉堡”,共计十几个毒气室;杀戮装置昼夜不停地运行。[109]经过犹太人站台(Judenrampe)上无情的“选择过程”之后,每天有多达6,000人被毒气杀害并火化。[110][111]帝国安全总办(RSHA)组织的运输中,只有大约10%的被驱逐者得到登记并分配到比克瑙的营房。[111]

奥斯威辛II号营的灭绝计划导致130万至150万人死亡。[112] 其中超过110万是来自欧洲各地的犹太人,包括20万名儿童。[106][113]有40万名受害者得到了登记,不到奥斯威辛到达总人数的三分之一;这40万人中有14万-15万名非犹太波兰人、2.3万名吉普赛人,1.5万名苏联战俘和2.5万其他受害者。[112][114]奥斯威辛从德占波兰得到了大约30万犹太人,[115]他们是从中转营和被清场的隔都用货运列车运来的。[116]向奥斯维辛的运输从比托姆开始(1942年2月15日)、随后是奥尔库什(6月中的三天)、奥特沃茨克(在8月)、沃姆扎和切哈努夫(11月),[117]然后是克拉科夫(1943年3月13日)、[118] 索斯诺维茨、本津、栋布罗瓦(1943年6月至8月),[119]以及其他几十个大都市和城镇,[28]1944年8月,德占波兰境内最后一个隔都——罗兹隔都遭到清场,居民同样被遣送至奥斯维辛。[120]奥斯维辛-比克瑙集中营的毒气室和焚尸炉于1944年11月25日根据海因里希·希姆莱的命令被炸毁;纳粹企图以这种方式摧毁大规模杀戮的证据。[121]

特雷布林卡

[编辑]

特雷布林卡灭绝营专为杀人而设计和建造,是保存至今的三个此类设施之一——另外两个是贝乌热茨和索比布尔。[122]所有的这类杀人设施都位于远离人口中心的树木繁茂的地区,并通过铁路支线与波兰铁路系统相连。设施中有可调动的党卫队工作人员。[123]在铁轨旁边有一座铁路站台,周围是2.5米高的铁丝网围栏。营区中建造了大型营房,用于存放下车的受害者的财物。其中一座营房伪装成一座火车站,甚至配有假木钟和标牌,以防止新来的人意识到自己面临的命运。[124]通向毒气室的道路被称作“天堂之路”,用围栏封锁,沿途设有收银台用于收集护照和钱币,以便“妥善保管”。毒气室被伪装成公共淋浴间,背后是用挖掘机挖掘出的埋葬坑。[125]

特雷布林卡灭绝营位于华沙东北部80千米,[126]经过被逐出德国的劳改犯三个月的强制劳动建设后,于1942年7月24日开始运作。[127]从波兰首都运出犹太人的计划(“华沙大行动”)的计划随即立刻开始。[128][129][130]1942年夏季中的两个月里,约有25.4万名华沙隔都囚犯在特雷布林卡被消灭(一说至少有30万人)。[131]犹太人抵达特雷布林卡后立即被迫脱光衣服;他们随后以200人为一批关入双层毒气室,使用坦克引擎产生的废气处决。男人最先被处决,随后是妇女和儿童。[132][133][134]1942年8月至9月期间,毒气室以砖块重建并加以扩建,能够每天杀死12,000至15,000名受害者,[135]最多可在24小时内处死22,000人。[136]死者最初被埋在大型乱葬坑中,但腐烂尸体的恶臭在十公里以外都能闻到。[137]纳粹因此开始在由混凝土柱子和铁轨组成的露天烤架上焚烧尸体。[138]特雷布林卡运行的一年内在营中遇害的人数从80万到120万不等,确切数据不明。[139][140]1943年10月19日,在特雷布林卡囚犯起义后不久,该营地被奥迪洛·格洛博奇尼克关闭,[141]莱茵哈德行动此时已几乎完成。[139]

贝乌热茨

[编辑]

贝乌热茨灭绝营位于卢布林区贝乌热茨火车站附近,于1942年3月17日开始正式运作。灭绝营起初有三座临时搭建的毒气室;后来被六座由砖石和灰泥建造的毒气室取代,使该设施能够一次处理超过1,000名受害者。[142]至少有434,500名犹太人在贝乌热茨遇害。然而,由于该灭绝营缺乏可以核实的幸存者,因此它相对较为不出名。[143]死者尸体埋葬在乱葬坑中,由于腐烂而在高温下膨胀,使得土地开裂;贝乌热茨于1942年10月引入焚尸坑后解决了这个问题。[144]

武装党卫队的库尔特·戈尔施泰因在大屠杀期间负责从德意志害虫防治公司供应齐克隆B。[145]他在战后递交给盟军的《戈尔施泰因报告》中写道,1942年8月17日他在贝乌热茨目睹了45辆货车到达灭绝营,车上的6,700名囚犯中有1,450人已经死亡。[146]那列火车上的犹太人来自距离灭绝营不到一百公里的利沃夫隔都。[146][147]贝乌热茨的最后一批犹太人于1942年12月抵达灭绝营。[148]将挖掘出来的尸体烧毁的过程一直持续到次年3月。[149]其余500名特别支队囚犯见证了灭绝过程,拆除了营地,[143]随后在接下来的几个月里在附近的索比布尔集中营遭到处决。[150][151]

索比布尔

[编辑]

索比布尔集中营被伪装成离卢布林不远的铁路中转营,于1942年5月开始大规模毒气处决。[152]与其他灭绝中心一样,从清场的隔都和过境营地(伊兹比察和孔斯科沃拉)经大屠杀列车运来的犹太人会遇到一名穿着医用外套的党卫队队员。在索比布尔,党卫队二级小队长赫尔曼·米歇尔(Hermann Michel)命令囚犯接受“消毒”。[153]

新来的人被强制分成小组,交出他们的贵重物品,并在一座由院墙包围的院子里洗澡;特别支队的理发师负责剪掉女人的头发。脱掉衣服后,犹太人就被带到一条狭窄的小路上,进入伪装成淋浴间的毒气室。纳粹使用从红军坦克中取出的汽油发动机产生毒气,由排气管释放出一氧化碳气体。.[154]受害者的尸体被取出毒气室,放在露天坑上的铁架上火化(纳粹使用了人体脂肪作为部分燃料);遗骸被倾倒在七座“骨灰山”上。在索比布尔遇害的波兰犹太人总数估计至少为17万人。[155]1943年10月14日,集中营发生了囚犯起义,是仅有的两起成功的灭绝营犹太特别支队囚犯起义之一。300人在起义中逃亡,其中大多数被党卫队重新抓捕后处决。海因里希·希姆莱随即下令拆除集中营。[156][157]

卢布林-马伊达内克

[编辑]

和索比布尔灭绝营一样,马伊达内克集中营同样位于卢布林郊区。集中营在斑疹伤寒疫情期间短暂关闭,于1942年3月为莱茵哈德行动重新开启。马伊达内克起初用于储存从贝乌热茨、索比布尔和特雷布林卡的受害者身上偷来的贵重物品,[158]后来成为一个大量消灭波兰东南部犹太人口(如克拉科夫、利沃夫、扎莫希奇、华沙)的灭绝营。1942年末,马伊达内克集中营中建造了毒气室。[159]

波兰犹太人直接在其他囚犯的众目睽睽之下遭遇毒气处决,杀戮设施四周没有任何围栏。[160]根据一位目击者的证词,“为了掩盖垂死者的哭喊,毒气室附近开着拖拉机引擎。”死者随后被带到火葬场。马伊达内克的7.9万名受害者中有5.9万波兰犹太人。[161][162]1943年11月初,马伊达内克举行了“丰收节行动”,是整个战争期间德国单次屠杀犹太人最多的一次行动。[89]行动结束后,集中营只剩下71名犹太人。[163]

武装抵抗与隔都起义

[编辑]

大众通常错误地认为大多数犹太人被动地接受死亡的命运;[164]然而这是彻头彻尾的谬误。[165]犹太人对纳粹的抵抗不仅包括武装斗争,还包括精神上和文化上的抵抗;尽管隔都中的生活条件极不人道,但犹太人从精神抵抗中获得了尊严。[166][167]尽管长老们担忧反纳粹叛乱会招致对妇女和儿童的大规模报复,但犹太人中仍存在许多形式的抵抗。[168]随着德国当局开始清理隔都,波苏1939年边界两侧的100多个地点出现了武装抵抗,绝大多数发生在波兰东部。[169]5座主要城市、45座省级城镇、5个座要集中营和灭绝营、以及至少18个强迫劳动营中爆发了起义。[170]

早在1942年7月22日,犹太人就在波兰东部的涅斯维日隔都发动了叛乱。9月3日,拉科瓦隔都爆发起义;米佐什隔都随后在10月14日爆发起义。1943年1月18日的华沙隔都枪决行动导致二战中最大规模的犹太人起义在1943年4月19日爆发。6月25日,琴斯托霍瓦隔都爆发起义。1943年8月2日,特雷布林卡灭绝营的特别支队装备偷来的武器袭击了营地守卫。一天后,本津隔都和索斯诺维茨隔都爆发了起义。8月16日,比亚韦斯托克隔都起义爆发。10月14日,索比布尔集中营发生叛乱。1944年10月7日,起义者炸毁了奥斯威辛-比克瑙的一座焚尸炉。[169][170]卢茨克、马佐夫舍地区明斯克、平斯克、波尼亚托瓦与维尔纽斯也爆发了类似的抵抗运动。[171]

波兰人与犹太人

[编辑]只有10%的波兰犹太人在种族灭绝中幸存下来,这一比例是除了立陶宛以外各纳粹占领国中最低的。然而,波兰民族的救援者占以色列犹太大屠杀纪念馆认定的“国际义人”中的大多数。根据古纳尔·保罗森的说法,被认定的这些波兰人(超过6,000人)可能“只代表波兰救援者的冰山一角”。[172]一些犹太人得到了德占波兰的抵抗运动组织热戈塔委员会的有组织援助,这是波兰在德国占领的波兰抵抗的地下组织。[173]

1941年11月10日,汉斯·法郎克将死刑范围扩大到“以任何方式”援助犹太人的波兰人,包括“带他们在家住一晚,或让他们搭任何类型的便车”,或者“喂养逃跑的犹太人,或卖给他们食物”。[174]该法律在所有主要城市以海报广而告之。德国人在东部前线上控制的其他地区也发布了类似的规定。[175]超过700多名波兰国际义人的称号是追授的,因为他们早已因帮助或庇护他们的犹太邻居而被德国人杀害。[176]以色列犹太大屠杀纪念馆认可的波兰义人中有许多来自首都。古纳尔·保罗森在对华沙犹太人的研究中证明,尽管条件更为严峻,但华沙的波兰公民援助和隐藏犹太人的比例与据信“更安全”的西欧德占城市相当。[177]

反犹太主义

[编辑]波兰的反犹主义根深蒂固,有两个主要的动机:其一是声称犹太人污蔑了天主教信仰;其二是所谓的犹太共产主义学说。在20世纪30年代,波兰的天主教期刊可以和西欧的社会达尔文主义反犹主义和纳粹的传媒相当。然而,教会的教条禁止暴力行为,而直到20世纪30年代中期暴力行为才变得更加普遍。与德国的反犹太主义不同,波兰的反犹太主义者反对对犹太人实施种族灭绝或反犹骚乱的主张,而是主张大规模的移民。[178]德国和苏联的占领带来了波兰反犹主义的突然高潮。波兰人的看法基于认定共产党人有着“犹太合作”,以及波兰民族自身对犹太人的仇恨。勒索犹太人以及向德国当局告发犹太人的“猪油仔”也是普通的波兰人,但他们的行为不在全波兰民族的共识范围之内。巴巴罗萨行动之后,波兰人在1941年的耶德瓦布内反犹骚乱中袭击并杀害了犹太人,波兰东部的其他地方也发生了类似事件。1944年至1946年间也有波兰人殴打和杀害犹太人的事件,其中包括凯尔采反犹骚乱;这一时期类似事件的主要诱因是波兰人接管的犹太财产的处置问题。[179]

救援与援助

[编辑]

根据现代标准,绝大多数波兰犹太人都属于“显著的少数民族”,可以通过语言、行为和外表来区分。[180]在1931年的波兰全国人口普查中,只有12%的犹太人宣称波兰语是他们的第一语言,而79%的人将意第绪语列为他们的母语,另有9%的希伯来语母语者。[181]在包括波兰省会城市在内的许多城市与乡镇的劳动力市场中,存在数量庞大且文化不适应的少数群体,[180],导致了竞争压力。[182]然而古纳尔·保罗森总结道,不能因此而直接得到战时波兰人-犹太人关系的相关结论:当犹太人大屠杀开始后,“如果不考虑战争行为和纳粹的背信弃义,一个躲藏在华沙的犹太人活下来的机会绝不会比藏在荷兰更差。”[172]

在犹太人区隔都清场期临近结束时,大量犹太人设法逃到“雅利安”一方,[172]并在波兰救助者的帮助下生存。纳粹占领期间,大多数波兰人都在为自身的生存而绝望地斗争。他们无法阻止德国人消灭犹太人。1939年至1945年间,有近280万非犹太波兰人死于纳粹手中,15万人因苏联镇压而死亡;[183]死亡总数占波兰战前人口的五分之一。[184]他们的死因是故意的战争行为的结果,[185]包括大规模屠杀、集中营监禁、强迫劳动、营养不良、疾病、绑架和驱逐。[186]然而,有许多波兰人冒着死亡的风险隐藏整个犹太家庭,或以慈悲为由帮助犹太人。[187]如果犹太人被德国人发现,救助他们的波兰人有时会被这些犹太人告发,招致总督府内一整个援助网的灭顶之灾。[188]沙尔斯基-扎伊德勒(Żarski-Zajdler)引用数据称,与非犹太波兰人一同藏匿的犹太人人数约为45万。[187]可能有100万名非犹太波兰人帮助过他们的犹太邻居。[189]历史学家理查德·卢卡斯[6]估计波兰援助者的数量高达300万;这一数目与其他作者所引用的估计相似。[190][191][192][193]

1942年11月,波兰流亡政府最先在国际社会上揭示了德国运作的集中营的存在,以及对犹太人的系统性灭绝。[194]种族灭绝是由扬·卡尔斯基中尉以及威托德·皮雷茨基上尉向盟军报告的。皮雷茨基自愿被监禁在奥斯威辛集中营以收集情报,随后为西方撰写了100多页的官方报告。[195]

1942年9月,为了拯救犹太人,援助犹太人临时委员会(Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom)在佐菲亚·科萨科-什丘斯卡的倡议与波兰地下国的财政援助下成立。临时委员会由尤利安·格罗贝尔尼主持的犹太人援助委员会(Rada Pomocy Żydom,代号“热戈塔”)取代。目前尚不清楚有多少犹太人受到热戈塔的帮助,但在1943年的某一时期,仅在华沙就有2,500名犹太儿童受到热戈塔的伊雷娜·森德勒的照顾。自1942年起,热戈塔获得了近2900万兹罗提(超过500万美元),用于向波兰数千个犹太家庭提供救济金。[196]流亡政府还向犹太战斗组织和犹太军事联盟等犹太抵抗组织提供特别援助——包括资金、武器和其他物资。[197]

机会主义与勾结者

[编辑]

整个第二次世界大战期间,波兰从未组建任何纳粹勾结者政府。[198]正如彼得罗夫斯基指出,“波兰人中从来没有出现过吉斯林分子或任何特别的波兰党卫队师。相比之下,几乎所有其他欧洲国家都为纳粹德国提供了这两种勾结者。”[199]波兰地下国强烈反对在反犹迫害中的合作,并代表波兰救国军军事法庭威胁称所有针对他们的线人将会被处死。[200]然而,持续的战争暴行导致波兰传统社会规范和价值观崩溃。[201][202]有些人背叛了躲藏起来的犹太人,连同保护他们的波兰人。[203]根据波兰特别法庭的叛国罪死刑判决数量,敲诈勒索犹太人的人数约有数千人。.[204]古纳尔·保罗森在他的评论中表示,他可能会认定2万名波兰人拥有“丑陋的企图”。[205]大屠杀的证词证实,当犹太人被困在隔都时,一些犹太人利用了其他犹太人社会经济地位的内幕信息获利(参见13号小组)。[201]

约翰·康奈利和莱谢克·贡德克认为,在欧洲和世界历史的背景下,波兰的通敌现象是边缘化的。[198]首次违反道德界限的行为发生在 苏联占领时期:1940年-1941年期间,苏联将波兰人家庭大规模向东发配至西伯利亚,内务人民委员部武装的犹太民兵(opaskowcy)参与了相关行动。[206][207][208][209]1941年7月10日,在巴巴罗萨行动开始时,300多名耶德瓦布内的犹太人被一群波兰人活活烧死在一座谷仓里;根据国家记忆研究院最终调查结果,德国的秩序警察当时也在现场。[210]关于耶德瓦布内事件的经过仍然存在争议;争论的因素包括部署在比亚里斯托克区的齐辛瑙-施罗特斯堡别动队(由党卫队二级突击队中队长赫尔曼·沙佩尔领导)的作用、[211][212]德国纳粹的压力,以及广泛存在的对犹太人1939年热烈欢迎红军的憎恨。[206][207][208][209]

根据政治家斯特凡·科尔本斯基的说法,国家武装部队(NSZ)的一些成员参与了对亲苏联地下组织的犹太人成员的处决。[213]历史学家理查德·卢卡斯和塔德乌什·彼得罗夫斯基写道,NSZ向犹太人提供援助,并将他们与波兰国际义人一起列入他们的队伍。[214]NSZ圣十字旅救出了霍利绍夫集中营的约1,000名囚犯中的280名犹太妇女。NSZ的一名犹太游击队员菲力克斯·帕利(Feliks Parry)表示,他们中的大多数人“对他们组织的意识形态基础没有丝毫概念”而且并不关心,只关注抵抗纳粹分子。[215]在战后的波兰,共产党秘密警察经常折磨NSZ叛乱分子,迫使他们承认杀害了犹太人,以及犯下了其他所谓的罪行;其中最值得注意的是1946年在卢布林对23名NSZ军官的审判。即使审讯结束,公安部对政治犯的折磨并不会停止。如果NSZ被告在法庭上翻供否认“杀害犹太人”,也会遭受肉体折磨。[216]

波兰民族是否属于犹太人大屠杀的受害者

[编辑]纳粹对东欧的长期计划包括波兰的种族清洗,据纳粹估计该计划会导致约85%的波兰人死亡。[217]截至战争结束时,该计划大部分没有实现。

根据Donald Niewyk和Francis Nicosia的说法,“波兰人和其他斯拉夫人团体是否属于犹太人大屠杀受害者”这一问题,取决于是应根据纳粹的动机界定大屠杀,还是应根据纳粹实现其种族议程的程度来界定大屠杀。采取第一种立场的人认为,纳粹在波兰、乌克兰、白俄罗斯和苏联的暴行是“纳粹蔑视'非人'的直接结果”;[5]:49采取第二种立场的人指出,这些人的死亡“比犹太人、吉普赛人和残疾人(的灭绝)更具选择性”,并且很难区分“出于种族动机杀害的波兰人和苏联公民,[以及]德国军事行动直接或间接杀害的两国公民。”[5]:49Niewyk和Niocosia自身认同第二种立场。[5]:52

波兰少数民族在犹太人大屠杀中的角色

[编辑]| 波兰犹太人历史系列的一部分 |

| 波兰犹太人和犹太教史 |

|---|

| 波兰犹太人历史 |

| 20世纪 |

| 波兰国际义人 |

| 1989年至今 |

| 波兰犹太人历史时间轴 |

| 波兰犹太人列表 |

二战爆发前的波兰共和国是一个多元文化的国家,其人口的近三分之一来自少数民族:13.9%的乌克兰人; 10%的犹太人; 3.1%白俄罗斯人; 2.3%的德裔;以及3.4%的捷克人、立陶宛人和俄罗斯人。[218]波兰1918年重获独立之后不久,来自苏维埃共和国的大约50万难民在最初的自发逃亡中来到波兰。难民中以来自乌克兰的居多(参见栅栏区)——内战期间乌克兰发生了多达2,000起反犹骚乱。[219]在1919年11月到1924年6月的第二次移民浪潮中,约有120万人离开苏联领土前往新生的波兰。据估计约有46万名难民将波兰语作为第一语言。[218][220]1933年至1938年间,约有2.5万名德国犹太人逃离纳粹德国前往波兰寻求庇护。[221]

约有一百万波兰公民属于德裔少数民族。[222]1939年德苏入侵之后,又有118万名说德语的人来到波兰,其中有些来自帝国,也有些来自东部的几乎一无所有的德意志裔人。[223]数百名德裔波兰人加入了纳粹的德意志裔自卫队,以及1940年5月大区长官汉斯·法郎克在克拉科夫成立的特勤队部队。[224][225]在逃往波兰总督府辖区的大约3万名乌克兰民族主义者中,有数千人加入了乌克兰民族主义组织冲锋队,在克拉科夫区的各个德国基地接受培训,担任破坏者、口译员和民兵。[226][227]

在具有相当数量的德裔和亲德少数民族的城市,特勤队的存在对试图帮助隔都犹太人的非犹太波兰人构成了严重威胁:伊兹比察、卢茨克和马佐夫舍地区明斯克等地的隔都就属于这种情况。苏联入侵波兰前东部领土之后,俄罗斯人占领的东部省份产生了特别明显的反犹太主义态度。波兰当地人民目睹了苏联镇压自己同胞,并大规模流放至西伯利亚[17][206]。苏联安全机构执行了迫害波兰人的行动;此外,一些当地犹太人组成民兵,接管关键行政职务,[228]并与内务人民委员部合作。其他人则认为,在复仇的推动下,犹太共产党人在背叛波兰族和其他非犹太人的受害者方面表现突出。[209][229]

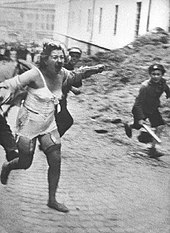

受德国启发的屠杀事件

[编辑]波兰东部占领区发生了多起受德国人启发的大屠杀事件,本地人民的积极参与其中。这种大屠杀的指导方针是莱因哈德·海德里希制定的:[230]他命令他的军官在德国军队新占领的领土上挑拨反犹太骚乱。[231][232]在战前波兰第五大城市,维尔诺省首府维尔诺(今维尔纽斯)的隔都建立前,[233]德国支队和立陶宛辅助警察营在1941年末的博纳利大屠杀期间杀死了21,000多名犹太人。[234]当时,维尔诺只有一小部分讲立陶宛语的少数民族,约占该市人口的6%.[235]在乌克兰武装分子在东部城市利沃夫犯下的一系列反犹骚乱中,大约6,000名波兰犹太人在1941年6月30日至7月29日期间在街头遇害,其中有3,000人被C别动队逮捕并枪决。[236][237]由乌克兰民族主义者组织(OUN)组建的乌克兰民兵组织在党卫队的赞许下,在波兰东南部的数十个地点散播恐怖。[238]

早在塔尔诺波尔省省会的隔都成立之前,国防军抵达该市两天后,塔尔诺波尔就有多达2,000名犹太人被杀,[239]其中三分之一被乌克兰民兵杀害;[240]部分受害者被斩首。[241]剩下的三分之二受害者由党卫队在同一周内枪杀。[240]1941年10月12日,在波兰前东部领土的另一座省会城市——斯坦尼斯瓦乌夫(现乌克兰伊万诺-弗兰科夫斯克)——发生了莱茵哈德行动之前单次屠杀波兰犹太人数最多的屠杀事件。这次称作“血腥星期天”的屠杀行动由秩序警察、安全警察与自利沃夫赶来的乌克兰辅警共同实施;作为刑场的公墓旁边设有放着伏特加和三明治的野餐桌,供需要在震耳欲聋的枪声中休息的处决者使用。在夜幕降临前,有12,000名犹太人被杀害。[242]

白俄罗斯、立陶宛与乌克兰的辅助警察(Schuma)共同在波兰东部地区参与了31起致命的反犹骚乱。[243]从德国人那里学到的种族灭绝技术——例如先进的平定行动计划、选址和突然的包围——成为了乌克兰反抗军1943年3月开始的瓦莱尼亚与东加利西亚波兰人与犹太人大屠杀的标志。这一屠杀行动与由希姆莱下达的“东方总计划”中的隔都清场行动并行。[244][245]成千上万逃离驱逐行动并藏匿在森林中的犹太人被班德拉派杀害。[246]

生还几率

[编辑]关于犹太人在大屠杀开始后真正的生存机会的问题持续引起历史学家的注意。[172]首先,德国人有意让逃离隔都变得非常困难,犹太人在驱逐到灭绝营之前几乎无法逃出隔都。驱逐行动被欺骗性地伪装成“在东方重新安置”。所有通行证都被取消,重建的墙壁减少了大门数量,警察由党卫队队员取代。一些已经被驱逐到特雷布林卡的受害者被迫向家中写信报平安。还有约3,000人进入了德国的“波兰人酒店”陷阱。许多隔都犹太人直到最后才相信正在发生的事情,因为事态实际的结果在当时似乎是不可想象的。[172] 大卫·朗道表示,弱势的犹太领导可能在屠杀中发挥了作用。[247]以色列·古特曼提出了类似观点,认为波兰地下国可能袭击营地并炸毁通往营地的铁轨。但正如保罗森所指出的,这样的想法是后见之明的产物。[172]

大屠杀幸存者的确切人数不详。战争开始后不久,可能有多达30万波兰犹太人逃到苏联占领区,有些估计的数量甚至更高。[248]值得注意的是,逃往东部的犹太人中有很大一部分是没有家人的男女。[248]成千上万人后来在瓦莱尼亚与东加利西亚波兰人大屠杀、白俄罗斯和立陶宛犹太人大屠杀(参见博纳利大屠杀)中死在乌克兰反抗军、立陶宛国家劳动保护旅(TDA旅)和立陶宛特别支队手上。[2][3]波兰总督府中的大多数波兰犹太人都留在了原地。[172]在大规模驱逐发生之前,人们认为没有必要离开熟悉的地方。当隔都从外面封锁时,大多数居民依靠走私的食物活着。约有10万名犹太人试图逃离隔都前往“雅利安”一侧的秘密地点;并且与普遍的误解相反,他们被波兰人出卖的风险非常小。[172]

据估计,大约有35万波兰犹太人在大屠杀中幸存下来。[25]其中约有23万人在苏联和苏联控制的波兰领土上幸存下来,其中包括逃离德国占领地区的人们。[25][23]二战结束后,超过15万(贝伦特)-18万(恩格尔)波兰犹太人被遣返或驱逐回新独立的波兰,红军1940年至1941年间从波兰前东部领土征召的年轻人也被遣返。他们的家人大多在大屠杀中丧生。[249]古纳尔·保罗森估计有3万名波兰犹太人在劳改营中幸存;[172]但根据恩格尔的说法,仅在德国和奥地利的营地中就有多达7万-8万人被解放,而且对于那些不打算返回的人而言,宣布自己的国籍无济于事。[7]切斯瓦夫·马达伊奇克估计,多达11万波兰犹太人在流离失所者营地。[250]根据隆格里奇的说法,多达5万名犹太人在森林中幸存(不计算加利西亚)[251],也有的在斯大林组建的亲苏的波兰“贝林格军”中重返波兰。成功藏匿在隔都“雅利安人”一侧的犹太人可能高达10万人(彼得·隆格里奇),[251]尽管由许多人被德国猎兵杀害。[251]战争结束后,并非所有幸存者都在波兰犹太人中央委员会(CKŻP)登记。数千名所谓的修道院儿童在战时被非犹太波兰人和天主教会藏匿起来,战后仍然留在玛丽家庭姊妹会在20多个地方经营的孤儿院,[252]其他天主教修道院也有相似行为。[253][254]

国界变化与遣返

[编辑]被列为最高机密的1939年苏德互不侵犯条约为第二次世界大战铺平了道路,而西方各国对该条约一无所知。[255][256]1945年5月德国投降后,欧洲的政治地理发生了巨大变化。[6][250]约瑟夫·斯大林在德黑兰会议期间提出了重新绘制了波兰边界的要求,并在1945年的雅尔塔会议上确认没有任何商量余地;盟国根据斯大林的要求重新划定了边界。[257]波兰流亡政府被排除在谈判之外。[258]波兰的领土减少了大约20%.[259]截至1946年底,约有180万波兰公民被驱逐出境并被强行安置在新的边界内。[257][258]在强权措施下,波兰在历史上第一次成为同质的民族国家。波兰的金融体系遭到破坏,国民财富减少了38%.新波兰人口减少了约33%,知识分子与犹太人一起被大量消灭。[259]

由于外部强加的领土转移,波兰的大屠杀幸存者的具体数量仍有争议。[250]据官方统计,该国犹太人的数量在很短的时间内发生了巨大变化。[260]1946年1月,波兰犹太人中央委员会(CKŻP)登记了来自附近的第一批约8.6万名幸存者。到了当年夏天结束时,这个数字上升到大约20.5-21万(注册人数为24万,重复登记数量超过3万)。[261]幸存者包括18万名由苏联控制的领土因遣返协议而来的犹太人。十年后,斯大林主义的迫害结束后,又有3万名犹太人从苏联返回波兰。[7][261]

欧洲的“阿利亚B运动”

[编辑]1946年7月,在意在巩固波兰共产党掌权的作假公投之后不久,四十名犹太人和两名波兰人在凯尔采反犹骚乱中丧生。[262]11名受害者死于刺刀伤口,还有11名因军用突击步枪的枪伤丧命(根据IPN的官方调查结果),表明正规部队直接参与了骚乱。[262]骚乱促使战时华沙出身的波兰工人党将军马里安·斯彼哈尔斯基[263]签署一项法令,允许剩余的幸存者在没有西方签证或波兰出境许可的情况下离开波兰。[264][261]波兰是唯一一个允许犹太人自由开展前往巴勒斯坦托管地的阿利亚运动的东方集团国家;斯大林勉为其难地批准了这类行为,试图削弱英国在中东的影响力。[7][260]越过波苏新边界的大多数难民在没有有效护照的情况下离开波兰。[261]相比之下,经过雅尔塔会议的准许,苏联强制将本国犹太人从流离失所营带回苏联,而不顾他们的意愿。.[265]

波兰边境上的不间断交通急剧增加。[266][7][267]到1947年春天,只有9万犹太人仍留在波兰。[268][269][270]英国要求波兰(以及其他国家)制止犹太人的外流,但他们的压力基本上没有成功。[271]凯尔采教区在公开声明中谴责了凯尔采的大屠杀。在这封向所有教堂发表的声明中,教区谴责了反犹骚乱。娜塔莉亚·阿列克逊写道,声明“强调最重要的天主教价值观是对人类同胞的同情,和对人类生命的尊重。它还提到了反犹太暴力的败坏道德的影响,因为暴行发生在青年和孩子面前。”牧师们在弥撒期间不予置评地阅读了公开声明,暗示“反犹骚乱可能实际上是一种政治挑拨。”[272]

1947年至1948年期间,大约7,000名达到服役年龄的犹太男女离开波兰前往巴勒斯坦托管地。他们是在波兰接受训练的哈加拿组织的成员,在下西里西亚的博尔库夫训练营由波兰犹太教官训练。哈加拿由美犹联合救济委员会与波兰政府达成协议提供资金。训练计划一直持续到至1949年初,主要训练22-25岁的男子,以备在以色列国防军服役。.[273]加入培训是离开波兰的一种便捷方式,因为课程毕业生不受边境管控,可携带未申报的贵重物品,甚至是管制枪械。[263]

大屠杀纪念馆和纪念活动

[编辑]

波兰有大量的纪念馆致力于纪念大屠杀。 1948年4月,华沙的隔都英雄纪念碑揭幕。主要的博物馆包括位于奥斯威辛郊区的奥斯维辛-比克瑙国家博物馆,每年有140万游客来访;还有位于华沙隔都旧址上的波兰犹太人历史博物馆,介绍了波兰犹太人的千年历史。[274][275]自1988年以来,一年一度的名为“生者之旅”的国际活动于4月的大屠杀纪念日在奥斯维辛-比克瑙旧址举行,共有超过15万名来自世界各地的年轻人参加。[276]

莱因哈德行动的每个灭绝营都建有国家博物馆。其中,卢布林的马伊达内克国家博物馆早在1946年就被宣布为国家纪念馆,其中有完整的二战时期的毒气室和火葬场。马伊达内克博物馆的分馆包括贝乌热茨博物馆及索比布尔博物馆;以色列和波兰的考古学家正在索比布尔的博物馆进行先进的地球物理研究。[277]新的特雷布林卡博物馆于2006年对外开放,后来扩建并成为位于一座原地方政府大楼中的谢德尔采地区博物馆的一座分馆。(另见谢德尔采隔都)。[278][279]内尔河畔海乌姆诺也设有一座小型博物馆。

注解

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Holocaust Encyclopedia -Trawniki. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. [21 July 2011]. (原始内容存档于August 29, 2015).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Snyder, Timothy (2004), The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press: pg. 162

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Turowski, Józef; Siemaszko, Władysław. Crimes Perpetrated Against the Polish Population of Volhynia by the Ukrainian Nationalists, 1939–1945 [Zbrodnie nacjonalistów ukraińskich dokonane na ludności polskiej na Wołyniu 1939–1945]. Warsaw: Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce – Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Środowisko Żołnierzy 27 Wołyńskiej Dywizji Armii Krajowej w Warszawie: Main Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Poland – Institute of National Remembrance with the Association of Soldiers of the 27th Volhynian Division of the Home Army, Warsaw 1990. 1990 [2019-03-19]. OCLC 27231548. (原始内容存档于2020-08-20).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Materski, Wojciech; Szarota, Tomasz; IPN. Poland 1939–1945. Human Losses and Victims of Repression Under Two Occupations [Polska 1939–1945. Straty osobowe i ofiary represji pod dwiema okupacjami]. Foreword by Janusz Kurtyka (Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance (IPN)). 2009. ISBN 978-83-7629-067-6. (原始内容存档于March 23, 2012) –通过Digital copy, Internet Archive.

The 2009 study published by the IPN revised the estimated Poland's war dead at about 5.8 million Poles and Jews, including 150,000 during the Soviet occupation,[4] not including losses of Polish citizens from the Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnic groups.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Niewyk & Nicosia (2012), p. 73

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Lukas (1989), pp. 5, 13, 111, 201,"Introduction". Also in:Lukas (2001), p. 13.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 David Engel, Poland (PDF), Liberation, Reconstruction, and Flight (1944–1947), The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, pp. 5–6 in current document, YIVO, "The largest group of Polish-Jewish survivors spent the war years in the Soviet or Soviet-controlled territories.", 2005, ISBN 9780300119039, [see also:] Golczewski (2000), p. 330, (原始内容 (PDF)存档于December 3, 2013)

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Cherry & Orla-Bukowska (2007), p. 137,'Part III Introduction' by Michael Schudrich.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. Contributors: Arnold Kramer, USHMM. Little Brown / USHMM. 1993. ISBN 978-0-316-09135-0. (原始内容存档于August 22, 2016).

—— Second ed. (2006) USHMM / Johns Hopkins Univ Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-8358-3, p. 140. - ^ 10.0 10.1 Aish HaTorah, Jerusalem, Holocaust: The Trains.Aish.com. Internet Archive.

- ^ Simone Gigliotti. Resettlement. The Train Journey: Transit, Captivity, and Witnessing in the Holocaust. Berghahn Books. 2009: 55 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1-84545-927-7. (原始内容存档于2020-09-20).

- ^ American Jewish Committee. (2005-01-30). "Statement on Poland and the Auschwitz Commemoration." 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期August 8, 2007,. Press release.

- ^ Yad Vashem, The Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Authority, Righteous Among the Nations - per Country & Ethnic Origin January 1, 2009. Statistics互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期August 18, 2010,.

- ^ www.yadvashem.org (2019)

- ^ Piotrowski (1998),Preface.

- ^ Levin, Nora. Annexed Territories. The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival, Volume 1 (NYU Press). 1990: 347 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8147-5051-3. (原始内容存档于2019-09-16).

Many Jews associated with the Bund, Zionist organizations, religious life, and 'bourgeois' occupations, were deported in April. The third deportation in June–July 1941 consisted mainly of refugees from western and central Poland who had fled to eastern Poland.[p.347]

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Materski & Szarota (2009),Source: Z.S. Siemaszko (1991), p. 95. ISBN 0850652103.

- ^ Sellars, Kirsten. 'Crimes Against Peace' and International Law. Cambridge University Press. 2013: 145 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1-107-02884-5. (原始内容存档于2019-10-01).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Eberhardt, Piotr. Political Migrations on Polish Territories (1939–1950) (PDF). Monographies. 2011, 12: 25, 27, 29. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于May 20, 2014) –通过Internet Archive, direct download.

- ^ David G. Williamson. Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939. Stackpole Books, 2011. 2011: 127. ISBN 978-0811708289. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018).

The Russians initially stressed that they were the protectors of the Poles and were Poland's `friendly Slavonic neighbour´!

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Wegner, Bernd. From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939–1941. Berghahn Books. 1997: 74 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1-57181-882-9. (原始内容存档于2021-03-15).

- ^ Moorhouse, Roger. The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939–1941. Basic Books. 2014: 28, 176 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0465054923. (原始内容存档于2019-10-16).

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Trela-Mazur, Elżbieta. Sovietization of educational system in the eastern part of Lesser Poland under the Soviet occupation, 1939–1941 [Sowietyzacja oświaty w Małopolsce Wschodniej pod radziecką okupacją 1939–1941]. Kielce: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna im. Jana Kochanowskiego. 1998: 43, 294 [1997]. ISBN 978-83-7133-100-8. Also in: Trela-Mazur (1997), studia wschodnie. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Wrocław: Wydawn. Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego. Volume 1, pp. 87–104.

- ^ Buwalda, Piet. They Did Not Dwell Alone: Jewish Emigration from the Soviet Union, 1967–1990. Woodrow Wilson Center Press. 1997: 16 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8018-5616-7. (原始内容存档于2019-09-30) –通过Google Books.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Jockusch, Laura; Lewinsky, Tamar. Paradise Lost? Postwar Memory of Polish Jewish Survival in the Soviet Union. Volume 24, Number 3. Winter 2010. Full text downloaded from the Holocaust and Genocide Studies (with signup). (原始内容存档于December 20, 2014).

- ^ Eberhardt & Owsinski (2003), pp. 199-201

- ^ 27.0 27.1 Paczkowski, Andrzej. The Spring Will Be Ours: Poland and the Poles from Occupation to Freedom. 由Cave, Jane翻译. Penn State Press. 2003: 54, 55–58. ISBN 978-0-271-02308-3. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018) –通过Google Books.

Further Reading: "Einsatzgruppen," at the Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 统计数据所用的资料包括波兰犹太人历史博物馆虚拟犹太镇的"Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland"互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期February 8, 2016,.、以及Gedeon 的 "Getta Żydowskie",以及Michael Peters 的 "Ghetto List". 2015年3月14日查阅。

- ^ Wardzyńska, Maria, The Year was 1939: Operation of German Security Police in Poland. Intelligenzaktion (PDF), (Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion) (Institute of National Remembrance), 2009, pp. 8–10 in current document [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-83-7629-063-8, PDF file, direct download 2.56 MB, (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2014-11-29) (波兰语).

- ^ Gilbert, Martin, The Holocaust: the Jewish tragedy, Collins: 84–85, 1986 [2019-03-19], (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Czesław Łuczak. Położenie ludności polskiej w Kraju Warty 1939–1945. Dokumenty niemieckie. Poznań: Wydawn. Poznańskie. 1987: V–XIII. ISBN 978-83-210-0632-1. Google Books.

- ^ Poles: Victims of the Nazi Era. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2013. (PDF version). (原始内容存档于October 3, 2013).

- ^ Rotbein Flaum, Shirley. Lodz Ghetto Deportations and Statistics. Timeline. JewishGen Home Page. 2007 [26 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-21).

Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust (1990), Baranowski, Dobroszycki, Wiesenthal, Yad Vashem Timeline of the Holocaust, others.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. The Łódź Ghetto. 2006 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2006-04-30).

Sources: Lodz Ghetto: Inside a Community Under Siege by Adelson, Alan and Robert Lapides (ed.), New York, 1989; The Documents of the Łódź Ghetto: An Inventory of the Nachman Zonabend Collection by Web, Marek (ed.), New York, 1988; The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry by Yahil, Leni, New York, 1991.

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. The Lódz Ghetto (1939–1945). History & Overview. Jewish Virtual Library. 2015 [1998] [19 March 2015]. (原始内容存档于April 2, 2015).

- ^ Postone, Moishe; Santner, Eric L. Catastrophe and Meaning: The Holocaust and the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. 2003: 75–6. ISBN 978-0-226-67610-4. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018).

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland (PDF). London, New York, Melbourne: Hutchinson & Co. Publishers: Polish government-in-exile, official report addressed to the wartime allies of the then-United Nations. 1942. pp. 1–16 (1–9 in current document).

- ^ Gruner, Wolf, Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis: Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938–1944, Cambridge University Press: 249–250, 2006 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0521838757, (原始内容存档于2020-05-11),

By the end of 1940, the forced-labor program in the General Government had registered over 700,000 Jewish men and women who were working for the German economy in ghetto businesses and as labor for projects outside the ghetto; there would be more.

- ^ Trunk, Isaiah. Judenrat: the Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe under Nazi Occupation. New York: Macmillan. 1972: 5, 172, 352 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8032-9428-8. with an introduction by Jacob Robinson. (原始内容存档于2020-09-30).

- ^ Louis Weber, Contributing Writers. 1939: The War Against the Jews. The Holocaust Chronicle: A History in Words and Pictures. Publications International. April 2000. (原始内容存档于March 20, 2012) –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ Michael Berenbaum. The World Must Know. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2006: 114 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 9780801883583. (原始内容存档于2020-12-12).

- ^ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Peter Vogelsang, Brian Larsen, The Ghettos of Poland, The Danish Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 2002, (原始内容存档于March 6, 2016) –通过Internet Archive

- ^ Marek Edelman. The Ghetto Fights. The Warsaw Ghetto: The 45th Anniversary of the Uprising. Literature of the Holocaust, at the University of Pennsylvania. (原始内容存档于November 25, 2009).

- ^ Browning, Christopher. The Path to Genocide: Essays on Launching the Final Solution. Cambridge University Press. 1995: 194 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-521-55878-5. (原始内容存档于2019-09-29) –通过Google Books.

- ^ Gutman, Yisrael. The First Months of the Nazi Occupation. The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt (Indiana University Press). 1989: 12 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-253-20511-7. (原始内容存档于2020-05-11).

- ^ 46.0 46.1 Emmanuel Ringelblum, Polish-Jewish Relations, p.86.

- ^ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Walter Laqueur, Judith Tydor Baumel, The Holocaust Encyclopedia, Yale University Press: 260–262, 2001, ISBN 978-0300138115

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Browning, Christopher, Before the "Final Solution": Nazi Ghettoization Policy in Poland (1940–1941) (PDF), Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, pp. 13–17 of 175 in current document, 2005, (原始内容存档 (PDF)于December 22, 2016).

- ^ Browning (2004), p. 229.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 217,"Ukrainian Collaboration."

- ^ Meehan, Meredith M. Auxiliary Police Units in the Occupied Soviet Union, 1941–43 (PDF). USNA. 2010: 1. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于June 6, 2016).

Without the auxiliaries, the Nazis' murderous intentions toward the Jewish population on the Eastern Front would not have been nearly as deadly.

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust by Bullets, 2017, (原始内容存档于August 11, 2017)

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 209,'Pogroms involving murder.'

- ^ Ronald Headland (1992), Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, pp. 125–126.ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.

- ^ Browning (2004), pp. 121–130,"Artificial famine."

- ^ Tal Bruttmann, Mémorial de la Shoah. Report: Mass graves and killing sites in the Eastern part of Europe (PDF). Grenoble: Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education and Research (ITF). 2010 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-08-11).

Mass graves resulting from deaths in the ghettos and various places of detention due to mistreatment, starvation ... concern the fate of several hundred thousand Jews. In the Warsaw ghetto alone, more than 100,000 Jews died and were buried in various places.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (2002), Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) New York: Vintage Books, pp. 243, 255. ISBN 0-307-42680-7.

- ^ Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Oxford University Press. 1991: 264–266, 270. ISBN 978-0195045239. (原始内容存档于February 22, 2017). Also in: Browning (2004), pp. 244, 321, 429.

- ^ Browning (2004), p. 244: For the global events at the end of 1941, see Battle of Moscow.

- ^ Thacker, Toby. Joseph Goebbels: Life and Death. Springer. 2016: 236, 258. ISBN 978-0230274228. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018).

Hitler made the decision to proceed with the mass murder of 'all the Jews of Europe' in the autumn of 1941.

- ^ Bauer, Yehuda. Rethinking the Holocaust. Yale University Press. 2000: 5 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0300093001. (原始内容存档于2020-05-11).

- ^ Minutes of the Conference, discovered in Martin Luther's files after the war: Selected Documents. Vol. 11: The Wannsee Protocol., [2019-03-19], (原始内容存档于2017-08-03)

- ^ Richard Rhodes, Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust, Knopf Doubleday: 233, 2007 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0307426802, (原始内容存档于2020-05-11)

- ^ Simone Gigliotti, The Train Journey: Transit, Captivity, and Witnessing in the Holocaust, Berghahn Books: 45, 2009, ISBN 978-1571812681, (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018)

- ^ 65.0 65.1 Bogdan Musial, David Cesarani, Sarah Kavanaugh , 编, The Origins of Operation Reinhard, Holocaust: From the persecution of the Jews to mass murder, 2004: 196–197 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0415275118, (原始内容存档于2020-05-11)

- ^ Cherry & Orla-Bukowska (2007),"Hilfswilliger." See: Trawnikis.

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik (2011), 405.[1] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Michael Thad Allen. The Business of Genocide: The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps. Univ of North Carolina Press. 2005: 139 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-26).

- ^ Dwork, Deborah and Robert Jan Van Pelt,The Construction of Crematoria at Auschwitz 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 14, 2014,. W.W. Norton & Co., 1996.

- ^ University of Minnesota, Majdanek Death Camp.互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期February 26, 2011,.

- ^ Cecil Adams, Did Krups, Braun, and Mercedes-Benz make Nazi concentration camp ovens?互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期June 4, 2011,.

- ^ Jack Fischel. The Holocaust. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1998: 129 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-313-29879-0. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Sereny, Gitta, Into That Darkness, Pimlico 1974, p. 48.

- ^ Lifton, Robert Jay (1986), The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide, Basic Books, p. 64.

- ^ Kate Connolly, Susanne Kill, German railways admits complicity in Holocaust, The Guardian (Berlin), January 23, 2008, (原始内容存档于September 3, 2017)

- ^ HOLOCAUST FAQ: Operation Reinhard: A Layman's Guide (2/2).Internet Archive.

- ^ 77.0 77.1 Hedi Enghelberg. The trains of the Holocaust. Kindle Edition. 2013: 63. ISBN 978-1-60585-123-5.

Book excerpts from Enghelberg.com.

- ^ Joshua Brandt. Holocaust survivor gives teens the straight story. Jewish news weekly of Northern California. April 22, 2005 [April 15, 2015]. (原始内容存档于November 26, 2005).

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik (2011),p. 95 (96 in current document). Testimony of Samuel Rajzman.([//web.archive.org/web/20190919015242/https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=https%3A%2F%2Fweb.archive.org%2Fweb%2F20161104145619%2Fhttp%3A%2F%2Fwww.polacyizydzi.com%2Fdam-im-imie-na-wieki.pdf&embedded=true&chrome=false&dov=1 页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Black, Edwin. IBM and the Holocaust. The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation (Crown Books 2001; Three Rivers Press 2002). 2001. OCLC 49419235. See also: Wikipedia article.. (原始内容存档于April 26, 2012).

- ^ German Railways and the Holocaust. The Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于May 6, 2009).

——Deportations to Killing Centers.互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期March 2, 2010,. Ibidem. - ^ AŻIH. Bronna Góra – Holocaust mass murder site [Bronna Góra – miejsce masowych egzekucji]. Museum of the History of Polish Jews Virtual Shtetl. 2014 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2017-08-03).

Testimony of B. Wulf, Docket nr 301/2212, Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

- ^ Garrard, John; Garrard, Carol. Monument at Bronnaya Gora. The Brest Ghetto Passport Archive. JewishGen. 2014. (原始内容存档于December 1, 2017).

- ^ Antopal: Brest. The Antopol Ghetto. The ghetto liquidation 'Aktion'. International Jewish Cemetery Project, with links to resources. [November 26, 2017]. (原始内容存档于August 4, 2017).

Deportations to Bronna Gora lasted four days beginning October 15, 1942

- ^ Burds, Jeffrey, Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941 (PDF), Northeastern University. Sponsored by the YIVO Institute of Jewish Research, New York, p. 2 (19 of 151 in current document), ISBN 9781137388391, (原始内容存档 (PDF)于August 3, 2017).

- ^ Połonka Mount, place of executions and the Holocaust mass grave [Górka-Połonka – miejsce egzekucji i zbiorowy grób ofiar Zagłady], POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, [2019-03-19], (原始内容存档于2017-08-04)

- ^ Yad Vashem, YouTube上的Mass-murder of Łuck Jews at Gurka Polonka in August 1942 注:波翁卡村(波兰语:Górka Połonka)以及它下辖的波翁卡丘(Połonka Little Hill互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 20, 2008,.)在纪录片中的拼写是错误的。该片有幸存者什穆尔·希洛的证词。

- ^ Marina Sorokina, Tarik Cyril Amar. The Holocaust in the East: Local Perpetrators and Soviet Responses. Pitt Series in Russian and East European Studies. University of Pittsburgh Press. 2014: 124, 165, 172, 255 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8229-6293-9. (原始内容存档于2017-10-14) –通过direct download 13.6 MB. 另见: Kerenji, Emil. Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1942–1943. Rowman & Littlefield. 2014: 69–70, 539. ISBN 978-1442236271.

- ^ 89.0 89.1 Browning, Christopher. Arrival in Poland (PDF). Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (Penguin Books). 1998: 52, 77, 79, 80, 135 [1992]. PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于October 10, 2014).

Also:PDF cache archived by WebCite.

- ^ ARC. Erntefest. Occupation of the East. ARC. 2004 [2013-04-26]. (原始内容存档于January 18, 2013).

- ^ Jochen Böhler, Robert Gerwarth. The Waffen-SS: A European History. Oxford University Press. 2017: 30 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0198790556. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

Streibel assigned detachments of Trawniki-trained men to guard and operate the killing centres [and] in support of deportation and shooting operations in the General Government.

- ^ Edward Crankshaw. Gestapo. A&C Black. 2011: 55–56 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1448205493. (原始内容存档于2022-01-01).

As part of Amt IV of the R.S.H.A., the SS, SD, Kripo, and Orpo were responsible for `the rounding up, transportation, shooting, and gassing to death of at least three million Jews.´

- ^ 位于波兰东南的普什库夫

- ^ Mirek Kusibab. HL-Heidelager: SS-TruppenÜbungsPlatz. History of the Range with photographs. Pustkow.Republika.pl. 2013. Historia poligonu Heidelager w Pustkowie. (原始内容存档于April 18, 2014) (波兰语).

- ^ Terry Goldsworthy. Valhalla's Warriors. A History of the Waffen-SS on the Eastern Front 1941–1945 (Dog Ear Publishing). 2010: 144. ISBN 978-1-60844-639-1 –通过Google Book preview.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship. Yale University Press. 2011: 109, 110, 113 [6 February 2015]. ISBN 978-0-300-13435-3.

- ^ The Simon Wiesenthal Center, Part 5, Responses to Revisionist Arguments, Museum of Tolerance., 1997 [2019-03-19], (原始内容存档于2017-04-03)另见:Henry Friedlander, From Euthanasia to the Final Solution (PDF), LBIHS, pp. 18–21 in current copy, 1995, (原始内容存档 (PDF)于April 18, 2015); International Tracing Service Catalogue, Brief Chronology Of the Konzentrationslager System, War Relics, 2013 [1949], (原始内容存档于July 28, 2014)

- ^ Browning (2004), pp. 191–192,"Adult euthanasia."

- ^ Montague, Patrick, Chełmno and the Holocaust: The History of Hitler's First Death Camp, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-8078-3527-2 –通过Google Books

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia – The Jews of Lodz. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2015 [12 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于April 19, 2015).

- ^ Michal Latosinski. Litzmannstadt Ghetto, Lodz. Traces of the Litzmannstadt Getto. A Guide to the Past: Introduction (Litzmannstadt Ghetto homepage). 2015 [12 April 2015]. ISBN 978-83-7415-000-2. (原始内容存档于December 23, 2017).

- ^ Shirley Rotbein Flaum, Roni Seibel Liebowitz. Lodz Ghetto Deportations and Statistics. Sources: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Baranowski, Dobroszycki, Wiesenthal, Yad Vashem Timeline. Łódź ShtetLinks · JewishGen. 2007 [12 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于2015-03-21).

- ^ JTA. Jewish Survivors of Chelmno Camp Testify at Trial of Guards. Internet Archive. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. January 22, 1963 [2013-06-14]. (原始内容存档于February 20, 2014).

- ^ Fluchschrift. 01.11.1941. Errichtung des ersten Vernichtungslagers in Chelmno. Heiner Lichtenstein, Daten aus der Zeitgeschichte, in: Tribüne Nr. 179/2006. Fluchschrift – Deutsche Verbrechen. 2013 [2013-06-14]. (原始内容存档于May 17, 2012).

- ^ Andrew Rawson, Auschwitz: The Nazi Solution, Pen and Sword: 121, 2015 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-1473827981, (原始内容存档于2020-08-19)

- ^ 106.0 106.1 Memorial and Museum. Auschwitz as a center for the extermination of the Jews. Jews in Auschwitz. Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. 2015 [13 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于March 20, 2016).

Countries of origin, Selection in the camp, Treatment.

- ^ Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum (2008), SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Fritsch "testing" the gas. 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期September 30, 2006,. (Internet Archive: The 64th Anniversary of the Opening of the Auschwitz Camp) Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, Poland (Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau w Oświęcimiu).

- ^ Institut Fuer Zeitgeschicthe (Institute for Contemporary History). Gassing Victims in the Holocaust: Background & Overview. Extermination camps in occupied Poland. Munich, Germany: Jewish Virtual Library. 1992. (原始内容存档于May 29, 2015).

- ^ Naomi Kramer, Ronald Headland, The Fallacy of Race and the Shoah, University of Ottawa Press: 254, 1998 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0776617121, (原始内容存档于2020-08-19) 另见: Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Yale University Press: 948–949, 2003 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0300095920, (原始内容存档于2020-08-19)

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia –Gassing Operations. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. [15 June 2015]. (原始内容存档于February 8, 2015).

- ^ 111.0 111.1 Vincent Châtel & Chuck Ferree. Auschwitz-Birkenau Death Factory. The Forgotten Camps. 2006 [13 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于April 3, 2015).

- ^ 112.0 112.1 Franciszek Piper. Number of deportees by ethnicity. Ilu ludzi zginęło w KL Auschwitz. Liczba ofiar w świetle źródeł i badań, Oświęcim 1992, tables 14–27. Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. 2015 [14 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于September 19, 2016).

- ^ Rees, Laurence. Auschwitz: A New History. 2005, Public Affairs, ISBN 1-58648-303-X, p. 168–169

- ^ Auschwitz-Birkenau Foundation. The Number and Origins of the Victims. How many people were registered as prisoners in Auschwitz?. History of KL Auschwitz (报告) (Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum). 2015. (原始内容存档于August 2, 2015).

- ^ Timothy Snyder, Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, Basic Books: 314, 2012, ISBN 978-0465032976, (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018)

- ^ Deborah Dwork, Robert Jan van Pelt (1997), Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Norton Paperback edition, ISBN 0-393-31684-X, p. 336–337.

- ^ Ber Mark, Isaiah Avrech, The Scrolls of Auschwitz, Am Oved: 71, 260, 1985 [2019-03-19], ISBN 9789651302527, Hometown ofRóża (Roza) Robota., (原始内容存档于2020-08-20)

- ^ Pressac, Jean-Claude; Van Pelt, Robert-Jan. The Machinery of Mass Murder at Auschwitz. Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp by Gutman, Yisrael & Berenbaum, Michael (Indiana University Press). 1994: 232 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Book of Sosnowiec and the Surrounding Region in Zaglembie. (原始内容存档于March 30, 2010).

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library, Overview of the Ghetto's history互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 1, 2015,.

- ^ Online Exhibitions: Give Me Your Children – Voices from the Lodz Ghetto. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于March 10, 2017).

- ^ Browning (2004), p. 374,camps designed to perpetrate mass murder.

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. 1999: 152–153 [1987]. ISBN 978-0-253-21305-1. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2018).

- ^ Testimony of Alexsandr Yeger互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期September 20, 2013,. at the Nizkor Project

- ^ Smith, Mark S. Treblinka Survivor: The Life and Death of Hershl Sperling. The History Press. 2010: 103–107 [9 April 2015]. ISBN 978-0-7524-5618-8. (原始内容存档于2020-10-17) –通过Google Books preview.

See Smith's book excerpts at: Hershl Sperling: Personal Testimony by David Adams, and the book summary at Last victim of Treblinka by Tony Rennell.

- ^ Steiner, Jean-François and Weaver, Helen (translator). Treblinka (Simon & Schuster, 1967).

- ^ Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik (2011), chapt. 3:1, p. 77.

- ^ Aktion Reinhard (PDF). Yad Vashem. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于March 11, 2017). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies. "Aktion Reinhard" was named after Reinhard Heydrich, the main organizer of the "Final Solution"; see also, Treblinka death camp built in June/July 1942 some 80 kilometres (50 mi) northeast of Warsaw.

- ^ Barbara Engelking: Warsaw Ghetto Internet Database互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 17, 2013,. hosted by Polish Center for Holocaust Research. 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期September 26, 2013,. The Fund for support of Jewish Institutions or Projects, 2006. (波兰文) (英文)

- ^ Barbara Engelking: Warsaw Ghetto Calendar of Events: July 1942互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期May 4, 2009,. Timeline. See: 22 July 1942 — the beginning of the great deportation action in the Warsaw ghetto; transports leave from Umschlagplatz for Treblinka. Publisher: Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów IFiS PAN, Warsaw Ghetto Internet Database互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 17, 2013,. 2006.

- ^ Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于February 12, 2010).

- ^ McVay, Kenneth. The Construction of the Treblinka Extermination Camp. Yad Vashem Studies, XVI. Jewish Virtual Library.org. 1984 [3 November 2013]. (原始内容存档于September 5, 2015).

- ^ Court of Assizes in Düsseldorf, Germany. Excerpts From Judgments (Urteilsbegründung). AZ-LG Düsseldorf: II 931638.

- ^ "Operation Reinhard: Treblinka Deportations"互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期September 23, 2013,. The Nizkor Project, 1991–2008

- ^ Ainsztein, Reuben. Jewish Resistance in Nazi-Occupied Eastern Europe. University of Michigan (reprint). 2008: 917 [1974] [21 December 2013]. ISBN 978-0-236-15490-6. (原始内容存档于May 3, 2016) –通过Google Books snipet view.

- ^ David E. Sumler, A history of Europe in the twentieth century. (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Dorsey Press,ISBN 0-256-01421-3.

- ^ Cymet, David. History vs. Apologetics: The Holocaust. Lexington Books. 2012: 278 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0739132951. (原始内容存档于2022-01-01).

In the town of Ostrow, thirteen miles [21千米] away from Treblinka, the stench was unbearable.

- ^ Klee, Ernst., Dressen, W., Riess, V. The Good Old Days: The Holocaust as Seen by Its Perpetrators and Bystanders. ISBN 1-56852-133-2.

- ^ 139.0 139.1 Kopówka & Rytel-Andrianik (2011),pp. 76–102 (of 610) in PDF.[2] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Musial, Bogdan (ed.), "Treblinka – ein Todeslager der Aktion Reinhard," in: "Aktion Reinhard" – Die Vernichtung der Juden im Generalgouvernement, Osnabrück 2004, pp. 257–281.

- ^ Arad (1999), p. 375.

- ^ Alex Bay. The Reconstruction of Belzec, featuring 98 photos. Holocaust History.org. 2015. Belzec. The Nazi Camp for Jews in the Light of Archaeological Sources by Andrzej Kola, translated by Ewa and Mateusz Józefowicz, The Council for the Protection of Memory of Combat and Martyrdom, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Warsaw-Washington [2000]. (原始内容存档于August 14, 2014). Belzec survivor Rudolf Reder, author of postwar memoir about Belzec wrote that the camp's gas chambers were rebuilt of concrete. No traces of concrete were found in archaeological studies. Instead, the brick rubble was found in excavations.

- ^ 143.0 143.1 Holocaust Encyclopedia – Belzec. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. [1 May 2016]. (原始内容存档于July 10, 2017).

- ^ Rudolf Reder. Bełżec. 1999 reprint by Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum with Fundacja Judaica in bilingual format, featuring English translation by Margaret M. Rubel. Preface by Nella Rost (ed.) (Kraków: Centralna Żydowska Komisja Historyczna division of the Central Committee of Polish Jews). 1946: 1–65 [28 May 2015]. OCLC 186784721. (原始内容存档于May 18, 2015) –通过WorldCat..

- ^ Yahil, Leni; Friedman, Ina; Galai, Hayah. The Holocaust: The fate of European Jewry, 1932–1945. Oxford University Press. 1991: 356–357 [2015-04-15]. ISBN 978-0-19-504523-9.

- ^ 146.0 146.1 Gerstein, Kurt, Gerstein Report in English translation [Der Gerstein-Bericht], Tübingen, 4 May 1945: Deathcamps.org, see, the Gerstein Report in Wikipedia, 1945, ISBN 978-90-411-0185-3, further reading: In the name of the people by Dick de Mildt. The Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1996, (原始内容存档于September 25, 2006).

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia – Belzec: Chronology. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于April 20, 2015).

- ^ Arad (1999), p. 102.

- ^ ARC contributing authors. Belzec Camp History. Aktion Reinhard Camps. 26 August 2006. (原始内容存档于December 25, 2005).

- ^ "Archeologists reveal new secrets of Holocaust", Reuters News, 21 July 1998

- ^ Belzec, Complete Book and Research互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期August 16, 2007,. by Robin O'Neil

- ^ Raul Hilberg. The Destruction of the European Jews. Yale University Press, 1985, p. 1219. ISBN 978-0-300-09557-9

- ^ Schelvis (2014), p. 70,Arrival and Selection.

- ^ Chris Webb, C.L. Former Members of the SS-Sonderkommando Sobibor describe their experiences in the Sobibor death camp in their own words. Belzec, Sobibor & Treblinka Death Camps. H.E.A.R.T. 2007 [16 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于September 6, 2011).

It was a heavy Russian benzine engine – presumably a tank or tractor motor at least 200 horsepower V-motor, 8 cylinders, water cooled (SS-Scharführer Erich Fuchs).

- ^ Schelvis (2014), p. 110.

Sobibór branch of the Majdanek State Museum. History of the Sobibór extermination camp. 2016. (原始内容存档于January 18, 2017).

Holocaust Encyclopedia – Sobibor. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于May 29, 2017). - ^ Schelvis, Jules. Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp. Berg, Oxford & New Cork, 2007, p. 168, ISBN 978-1-84520-419-8.

- ^ Sobibor Death Camp HolocaustResearchProject.org. (原始内容存档于October 9, 2014).

- ^ Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp: Conditions. The Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2003. (原始内容存档于August 16, 2012).

- ^ Rosenberg, Jennifer. Majdanek: An Overview. 20th Century History. about.com. 2008. ISBN 978-0-404-16983-1. (原始内容存档于July 5, 2004).

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library 2009, Gas Chambers at Majdanek互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 14, 2014,. The American-Israeli Cooperative

- ^ Kranz, Tomasz. Ewidencja zgonów i śmiertelność więźniów KL Lublin [Records of deaths and mortality of KL Lublin prisoners] (PDF) 23. Lublin: Zeszyty Majdanka: 7–53. 2005 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-01-18).

- ^ Reszka, Paweł P. Majdanek Victims Enumerated. Changes in the history textbooks?. Gazeta Wyborcza. December 23, 2005 [March 5, 2015]. (原始内容 (Internet Archive)存档于November 6, 2011).

- ^ Lawrence, Geoffrey; et al (编). Session 62: February 19, 1946. The Trial of German Major War Criminals: Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany 7. London: HM Stationery Office. 1946: 111. ISBN 978-1-57588-677-0. (原始内容存档于May 16, 2013).

- ^ Yad Vashem, An Interview With Prof. Yehuda Bauer (PDF), Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies, pp. 28–30 of 58 in current document, 2000, (原始内容存档 (PDF)于March 20, 2009).

- ^ Patrick Henry. The Myth of Jewish Passivity. Jewish Resistance Against the Nazis. CUA Press. 2014: 22–23 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0813225890. Prevalent misconception in most discussions about the Jewish resistance during World War II. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Feinberg, Stephen. Teaching and Studying the Holocaust. IAP. 2009: 52, 104, 150, 282 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1607523017. Human dignity and spiritual resistance. (原始内容存档于2020-09-07). Also in: Gershenson, Olga. The Phantom Holocaust. Rutgers University Press. 2013: 104 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0813561820. (原始内容存档于2020-09-03).

- ^ Christopher Browning, Raul Hilberg, Yad Vashem Studies (Wallstein Verlag), 2001: 9–10 [2019-03-19], ISSN 0084-3296, (原始内容存档于2020-08-19)

- ^ Isaiah Trunk, The Attitude of the Councils toward Physical Resistance, Judenrat: The Jewish Councils in Eastern Europe Under Nazi Occupation, U of Nebraska Press: 464–466, 472–474, 1972, ISBN 978-0803294288, (原始内容存档于January 3, 2014),

The highest degree of cooperation was achieved when chairmen, or other leading Council members themselves, actively participated in preparing and executing acts of resistance, particularly in the course of liquidations of ghettos. [Prominent examples include Warsaw,Częstochowa, Radomsko, Pajęczno, Sasów, Pińsk, Mołczadź, Iwaniska, Wilno, Nieśwież, Zdzięcioł (see: Zdzięcioł Ghetto), Tuczyn (Równe), and Marcinkańce (Grodno) among others]

另见: Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust: the Jewish tragedy, Collins: 828, 1986 - ^ 169.0 169.1 The Holocaust Encyclopedia, Jewish Resistance, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2011, see map., (原始内容存档于January 26, 2012) –通过Internet Archive. 另见:Shmuel Krakowski, Armed Resistance, YIVO, 2010, (原始内容存档于June 2, 2011)

- ^ 170.0 170.1 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Resistance during the Holocaust (PDF), The Miles Lerman Center for the Study of Jewish Resistance, p. 6 of 56 in current document, (原始内容存档 (PDF)于August 29, 2017).

- ^ The Holocaust Encyclopedia, Resistance in the Vilna Ghetto, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2017, (原始内容存档于August 3, 2017)

- ^ 172.0 172.1 172.2 172.3 172.4 172.5 172.6 172.7 172.8 Gunnar S. Paulsson. The Rescue of Jews by Non-Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland. Journal of Holocaust Education. Summer–Autumn 1998, 7 (1&2): 19–44. doi:10.1080/17504902.1998.11087056. Relevant excerpt about the 'chances of survival in hiding.'.

Keeping in mind that these cases are drawn from published memoirs and from cases on file at Yad Vashem and the Jewish Historical Institute, it is probable that the 5,000 or so Poles who have been recognised as 'Righteous Among the Nations' so far represent only the tip of the iceberg, and that the true number of rescuers who meet the Yad Vashem 'gold standard' is 20, 50, perhaps even 100 times higher (p. 23, § 2; available with purchase).

- ^ Yad Vashem Shoa Resource Center,Zegota (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)[3] 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期October 20, 2013,.[4] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) October 20, 2013, at theWayback Machine. , page 4/34 of the Report.

- ^ Mordecai Paldiel. Gentile Rescuers of Jews. The Path of the Righteous (KTAV Publishing House Inc.). 1993: 184 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0881253764. (原始内容存档于2021-03-15).

- ^ for the Jews 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期May 11, 2018,., Jan Grabowski, page 55, Indiana University Press

- ^ Chefer, Chaim (2007), "Righteous of the World: List of 700 Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust." Internet Archive.

- ^ Unveiling the Secret City互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期June 12, 2007,. H-Net Review: John Radzilowski

- ^ This last statement is based on the fact that Polish Antisemitism, even during the war, was not murderous in nature and did not speak in terms of outright liquidation except on its outermost fringes. It expressed extreme messages and unequivocal conclusions–the imperative of mass Jewish emigration from Poland–but did not advocate pogroms or genocideWere These Ordinary Poles? Daniel Blatman Archived copy. [2018-05-19]. (原始内容存档于May 20, 2018).

- ^ and the Sporting Life: Studies in Contemporary Jewry XXIII (Polish Antisemitism: A National Pshychosis?)互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期May 15, 2018,., Daniel Blatman in volume edited by Ezra Mendelsohn, Oxford University Press, pages 213–225

- ^ 180.0 180.1 Stopnicka Heller, Celia. On the Edge of Destruction: Jews of Poland Between the Two World Wars. Wayne State University Press, 396 pages. 1993: 65 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8143-2494-3. (原始内容存档于2021-06-28).

- ^ Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności, 9.XII.1931 (PDF). Polish census of 1931. Table 10, page 30 in current document (Warsaw). 1938. PDF file, direct download. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于April 2, 2015) (波兰语).

Religion and Native Language (total). Section, Jewish: 3,113,933 with Yiddish: 2,489,034 and Hebrew: 243,539

. - ^ Norman Davies, God's Playground, (Polish edition), Second volume, pp. 512–513, 1979; Alice Teichova, Herbert Matis, Jaroslav Pátek, Economic Change and the National Question in Twentieth-century Europe: 342–344, 2000 [2019-03-19], ISBN 9781139427654, (原始内容存档于2020-09-24); Gedeon & Marta Kubiszyn, Business environment in 1926–1929, Jewish history of Radom (Virtual Shtetl), page 2 of 6, [2019-03-19], (原始内容存档于2017-08-11) (波兰语); Lubartow during the Holocaust in occupied Poland, Taube Foundation for Jewish Life and Culture, (原始内容存档于February 16, 2012).

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009),page 9.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), pp. 305–,'Poland's losses.'

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009),page 16.

- ^ Materski & Szarota (2009),page 28. Some 800,000 Poles perished in concentration camps and mass murders.

- ^ 187.0 187.1 Żarski-Zajdler, Władysław. Martyrologia ludności żydowskiej i pomoc społeczeństwa polskiego [Martyrdom of the Jewish people and their rescue by the Polish society]. Warsaw: ZBoWiD. 1968: 16 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0813143323. [in:] Lucas (2013), p.14. Note 21 to "Introduction.". (原始内容存档于2020-09-02).

- ^ Zajączkowski, Wacław. Christian Martyrs of Charity (PDF). Washington, D.C.: S.M. Kolbe Foundation. June 1988. pp. 152–178 (1–14 of 25 in current document) [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0945281009. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2015-02-18).

German military police in Grzegorzówka[p.153] and in Hadle Szklarskie[p.154] (Przeworsk County) extracted from two Jewish women the names of Christian Poles helping Jews – 11 Polish men were murdered. In Korniaktów forest (Łańcut County)[p.167] a Jewish woman caught in a bunker revealed the whereabouts of the Catholic family who fed her – the whole Polish family were murdered. In Jeziorko, Łowicz County,[p.160] a Jewish man betrayed all Polish rescuers known to him – 13 Catholics were murdered by the German military police. In Lipowiec Duży(Biłgoraj County),[p.174] a captured Jew led the Germans to his saviors – 5 Catholics were murdered including a 6-year-old child and their farm was burned. There were other similar cases; on a train to Kraków[p.170] the Żegota courier Irena who smuggled four Jewish women to safety was shot dead when one of them lost her nerve.

- ^ Hans G. Furth One million Polish rescuers of hunted Jews? Journal of Genocide Research, June 1999, Vol. 1 Issue 2, pp. 227–232; AN 6025705.

- ^ Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg. Needle in the Bone: How a Holocaust Survivor and a Polish Resistance Fighter Beat the Odds and Found Each Other. 2012: 6 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1612345680. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

Approximately 3 million Poles rescued, hid, or otherwise helped Jews during the war, and fewer than a thousand denounced Jews to the Nazis.

- ^ Richard Kwiatkowski. The Country That Refused to Die: The Story of the People of Poland. 2016: 347 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1524509156. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

The number of Poles estimated to be actively involved in the rescue of Jews is estimated between one and three million.

- ^ David Marshall Smith. Moral geographies: ethics in a world of difference. 2000: 112 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 9780748612789. (原始内容存档于2020-09-25).

It has been estimated that a million or more Poles were involved in helping Jews.

- ^ Lukas (1989), p. 13 – Recent research suggests that a million Poles were involved, but some estimates go as high as three million.Lukas, 2013 edition. 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 5, 2018,. ISBN 0813143322.

- ^ Note to the Governments of the United Nations – December 10th, 1942. Republika.pl. [2011-10-07]. (原始内容存档于July 22, 2012).

- ^ Pawłowicz, Jacek. Rotmistrz Witold Pilecki 1901–1948. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN. 2008: 254– [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-83-60464-97-7. (原始内容存档于2020-08-20) (波兰语).

- ^ Cesarani, David; Kavanaugh, Sarah. Holocaust. Routledge. : 64 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2021-12-28).

- ^ Stola, Dariusz (2003), "The Polish government in exile and the Final Solution: What conditioned its actions and inactions?" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) In: Joshua D. Zimmerman, ed. Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press.

- ^ 198.0 198.1 John Connelly, Why the Poles Collaborated so Little: And Why That Is No Reason for Nationalist Hubris.互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期July 5, 2018,. Slavic Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 771–781. In response to article by: Klaus-Peter Friedrich,Collaboration in a "Land without a Quisling": Patterns of Cooperation with the Nazi German Occupation Regime in Poland during World War II.互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期August 18, 2017,. Slavic Review, ibidem.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 84,'Quisling.'

- ^ Piotr Chojnacki; Dorota Mazek (编). Polacy ratujący Żydów w latach II wojny światowej [Poles rescuing Jews during World War II]. Zeszyty IPN, Wybór Tekstów (Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance). 2008: 7, 18, 23, 31.

Kierownictwo Walki Cywilnej w "Biuletynie Informacyjnym" ostrzega "szmalcowników" i denuncjatorów przed konsekwencjami grożącymi im ze strony władz państwa podziemnego. [p.37 in PDF] Ot, widzi pan, sprawa jednej litery sprawia ogromną różnicę. Ratować i uratować! Ratowaliśmy kilkadziesiąt razy więcej ludzi, niż uratowaliśmy. – Władysław Bartoszewski [p.7]

- ^ 201.0 201.1 Paul, Mark. Patterns of Cooperation, Collaboration and Betrayal: Jews, Germans and Poles in Occupied Poland during World War II (PDF). Glaukopis. Foreign language studies. September 2015. 159/344 in PDF [25 February 2016]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-03).

The Jewish looters knew better than anyone else "where to dig for valuables." Testimonies of Anzel Daches, Majer Gdański, Laja Goldman, Mojżesz Klajman, Chana Kohn, Jakub Libman, and Izrael Szerman, dated October 13, 1947; the Jewish Historical Institute Archive, record group 301, number 2932.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998),p. 66. 'Collaborating.'

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 66,"Blackmailers."

- ^ Lukas, Richard C. Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust. University Press of Kentucky. 1989: 13. ISBN 978-0813116921. Also in: Lukas, Richard C. The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation, 1939–1944. University Press of Kentucky. 1986: 120. ISBN 978-0781809016.

- ^ Dr. Paulsson's Commentary in Refuting the Editor's "Hate Poles" Campaign. isurvived.org. [2018-06-07]. (原始内容存档于June 12, 2018).

- ^ 206.0 206.1 206.2 Lerski, Jerzy Jan; Wróbel, Piotr; Kozicki, Richard J. Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. 1996: 110, 538 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. For the Soviet deportations' more recent IPN findings, see Materski & Szarota (2009),Introduction. (原始内容存档于2020-10-02).

- ^ 207.0 207.1 Barkan, Elazar; Cole, Elizabeth A.; Struve, Kai. Shared History, Divided Memory: Jews and Others in Soviet-occupied Poland, 1939–1941. Leipziger Universitätsverlag. 2007: 136, 151 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-3865832405. (原始内容存档于2019-08-22).

In dozens of towns and settlements, attacks were carried out by "militias", "self-defence groups" and opaskowcy (called such for the red armbands they wore), which were made up primarily of Jews and Belarussians.[p.151]

- ^ 208.0 208.1 Strzembosz, Tomasz. 由Jerzy Michałowicz翻译. Thoughts on Professors Gutman's Diary (PDF). Yad Vashem Studies. 2002, XXX: 7–20. PDF file, direct download. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于August 5, 2011).

The localities in question include: Grodno, Skidel (see the Skidel revolt), Jeziory, Łunna, Wiercieliszki, Wielka Brzostowica, Ostryna, Dubna, Dereczyn, Zelwa, Motol, Wołpa, Janów Poleski, Wołkowysk, and Drohiczyn Poleski.

- ^ 209.0 209.1 209.2 Pogonowski, Iwo Cyprian. Jedwabne: The Politics of Apology and Contrition. Panel Jedwabne – A Scientific Analysis. Georgetown University, Washington DC: Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America. June 8, 2002 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-19).

- ^ Jedwabne Tragedy: Final Findings. Info-poland.buffalo.edu. [2011-10-07]. (原始内容存档于March 3, 2016).

- ^ Rossino, Alexander B. Polish 'Neighbors' and German Invaders: Contextualizing Anti-Jewish Violence in the Białystok District during the Opening Weeks of Operation Barbarossa. Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry. 2003, 16. References: №58. The Partisan: From the Valley of Death to Mount Zion by Yitzhak Arad; №59. The Lesser of Two Evils: Eastern European Jewry under Soviet Rule, 1939–1941 by Dov Levin; and №97. Abschlussbericht, 17 March 1964 in ZStL, 5 AR-Z 13/62, p. 164. (原始内容存档于February 22, 2014) –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ Wróbel, Piotr. Polish-Jewish Relations. Dagmar Herzog: Lessons and Legacies: The Holocaust in international perspective (Northwestern University Press). 2006: 391–396 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8101-2370-0. (原始内容存档于2019-10-05).

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 95,Korboński's 1981 quote verifying claim.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), p. 96,Verification.

- ^ Piotrowski (1998), pp. 77–142,"NSZ underpinnings."

- ^ Chodakiewicz, Marek Jan, The Dialectics of Pain互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期August 22, 2006,. Glaukopis, vol. 2/3 (2004–2005). See also: John S. Micgiel, "'Frenzy and Ferocity': The Stalinist Judicial System in Poland, 1944–1947, and the Search for Redress," The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies [ Pittsburgh], no. 1101 (February 1994): 1–48. For concurring opinions see: Krzysztof Lesiakowski and Grzegorz Majchrzak interviewed by Barbara Polak, "O Aparacie Bezpieczeństwa," Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 6 (June 2002): 4–24; Barbara Polak, "O karach śmierci w latach 1944–1956," Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej, no. 11 (November 2002): 4–29.

- ^ Various authors. Generalplan Ost (General Plan East). The Nazi evolution in German foreign policy. Documentary sources. Versions of the GPO. Alexandria, VA: World Future Fund. 2003 [2019-03-19]. Resources: Janusz Gumkowski and Kazimierz Leszczynski,Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe. Ibid. (原始内容存档于2007-01-02).

- ^ 218.0 218.1 Gregorowicz, Stanisław. Rosja. Polonia i Polacy. Encyklopedia PWN. Online. Polish Scientific Publishers PWN. 2016. (原始内容存档于April 6, 2016).

- ^ Sharman Kadish. Bolsheviks and British Jews: The Anglo-Jewish Community, Britain, and the Russian Revolution. Routledge. 1992: 80 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-7146-3371-8. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Marcus, Joseph. Social and political history of the Jews in Poland, 1919–1939. Walter de Gruyter. 1983: 17–19. ISBN 978-90-279-3239-6. (原始内容存档于October 22, 2017).

- ^ Gilbert, Martin. The Routledge Atlas of the Holocaust. Psychology Press. 2002. p. 23, Map 15: Jewish Refugees Find Haven in Europe, 1933–1938 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-415-28146-1. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19) –通过Google Books.

- ^ Wróbel, Piotr. Historical Dictionary of Poland 1945-1996. Routledge. 2014: 108 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1135926946. (原始内容存档于2020-08-20).

- ^ Kosiński, Leszek A. Demographic developments in Eastern Europe. Praeger. 1977: 314 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Roszkowski, Wojciech. History: The Zero Hour [Historia: Godzina zero]. Tygodnik.Onet.pl weekly. 4 November 2008 [18 May 2014]. (原始内容存档于May 12, 2012).

- ^ The Erwin and Riva Baker Memorial Collection. Yad Vashem Studies. Wallstein Verlag. 2001: 57– [2019-03-19]. ISSN 0084-3296. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Cantorovich, Irena. Honoring the Collaborators – The Ukrainian Case (PDF). Roni Stauber, Beryl Belsky. Kantor Program Papers. June 2012 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-05-10).

When the Soviets occupied eastern Galicia, some 30,000 Ukrainian nationalists fled to the General Government. In 1940 the Germans began to set up military training units of Ukrainians, and in the spring of 1941 Ukrainian units were established by the Wehrmacht.

See also: Marek Getter. Policja w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie 1939–1945. Przegląd Policyjny nr 1-2. Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Policji w Szczytnie: 1–22. 1996. WebCite cache. (原始内容存档于June 26, 2013). - ^ Breitman, Richard. U.S. Intelligence and the Nazis. Cambridge University Press. 2005: 249 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0521617949. (原始内容存档于2020-10-17).

- ^ Lukas (2001),The forgotten Holocaust, page 128.

- ^ Strzembosz (2002), p. 1. Background information: Strzembosz, Tomasz. A different view of neighbors [Inny obraz sąsiadów] (31.03.01 Nr 77). Rzeczpospolita. 2001. (原始内容存档于June 10, 2001) –通过Internet Archive. As well as: Paul, Mark. Neighbours On the Eve of the Holocaust (PDF). Glaukopis. 2013. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于May 12, 2013).

- ^ Browning (2004), p. 262.

- ^ Michael C. Steinlauf. Bondage to the Dead. Syracuse University Press, p. 30.

- ^ Paweł Machcewicz, "Płomienie nienawiści", Polityka 43 (2373), October 26, 2002, p. 71–73 The Findings 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期March 10, 2009,.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz. Revolution from Abroad: The Soviet Conquest of Poland's Western Ukraine and Western Belorussia. Princeton University Press. 2002: 3. ISBN 978-0-691-09603-2.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. 2003: 84–89. ISBN 978-0-300-10586-5 –通过Google Books, preview.

- ^ Müller, Jan-Werner. Memory and Power in Post-War Europe: Studies in the Presence of the Past. Cambridge University Press. 2002: 47. ISBN 978-0-521-00070-3.

- ^ Longerich, Peter. Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. 2010: 194–. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5. (原始内容存档于February 1, 2017).

- ^ Holocaust Encyclopedia – Lwów. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (原始内容存档于March 7, 2012).

- ^ Dr. Frank Grelka. Ukrainischen Miliz. Die ukrainische Nationalbewegung unter deutscher Besatzungsherrschaft 1918 und 1941/42 (Viadrina European University: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag). 2005: 283–284 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-3-447-05259-7. (原始内容存档于2020-10-17).

RSHA von einer begrüßenswerten Aktivitat der ukrainischen Bevolkerung in den ersten Stunden nach dem Abzug der Sowjettruppen.

For the German administrative divisions of Polish kresy with prominent Jewish communities destroyed under Nazi occupation, see: Bauer, Yehuda, The Death of the Shtetl, Yale University Press: 1–6, 65, 2009 [2019-03-19], ISBN 978-0300152098, (原始内容存档于2020-09-26) - ^ Kuwałek, Robert; Riadczenko, Eugeniusz; Marczewski, Adam. Tarnopol. Virtual Shtetl. Translated by Katarzyna Czoków and Magdalena Wójcik: 3–4. 2015 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-31).

- ^ 240.0 240.1 Tarnopol Historical Background. Yad Vashem. Archived 9 March 2014. (原始内容存档于March 9, 2014).

- ^ Talking with the willing executioners. Haaretz.com 18 May 2009 via Internet Archive.

- ^ Pohl, Dieter. Hans Krueger and the Murder of the Jews in the Stanislawow Region (PDF). Yad Vashem Resource Center. : 12/13, 17/18, 21. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于12 August 2014) –通过direct download, PDF 95 KB.

It is clear that a massacre of such proportions under German civil administration was virtually unprecedented.

Andrea Löw. Holocaust Encyclopedia –Stanislawów (now Ivano-Frankivsk). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. [1 May 2016]. From The USHMM Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. (原始内容存档于February 2, 2017). - ^ Piotrowski (1998),Poland's Holocaust, page 209..另见:Eugeniusz Mironowicz. German-Belarusian Alliance [Idea sojuszu niemiecko-białoruskiego]. Okupacja niemiecka na Białorusi. Związek Białoruski w RP; Katedra Kultury Białoruskiej Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku. 2007. (原始内容存档于September 27, 2007) –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale University Press. 2003: 162–170. ISBN 978-0-300-10586-5. (原始内容存档于June 3, 2016).

- ^ Spector, Shmuel; Wigoder, Geoffrey. The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust. Volume III. NYU Press. 2001: 1627. ISBN 978-0814793787. (原始内容存档于December 31, 2013).

- ^ Rossolinski, Grzegorz. Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist : Fascism, Genocide, and Cult. Columbia University Press. 2014: 290 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-3838206844. (原始内容存档于2020-09-11).

- ^ Landau, David J., Caged — A story of Jewish Resistance, Pan Macmillan Australia, 2000, ISBN 0-7329-1063-3. Quote: "The tragic end of the Ghetto [in Warsaw] could not have been changed, but the road to it might have been different under a stronger leader. There can be no doubt that if the Uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto had taken place in August—September 1942, when there were still 300,000 Jews, the Germans would have paid a much higher price."

- ^ 248.0 248.1 Pinchuk, Ben Cion. Jewish refugees in Soviet Poland. Marrus, Michael Robert (编). The Nazi Holocaust. Part 8: Bystanders to the Holocaust, Volume 3. Walter de Gruyter. 1989: 1036–1038 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-3110968682. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

The range of differences in estimates might give us an idea of the problem's complexity. Thus, Avraham Pechenik estimated the number of refugees at 1,000,000.[p.1038]

- ^ Berendt, Grzegorz. Emigration of Jewish people from Poland in 1945–1967 [Emigracja ludności żydowskiej z Polski w latach 1945–1967] (PDF). Polska 1944/45–1989. Studia I Materiały. 2006, VII. pp. 25–26 (pp. 2–3 in current document). (原始内容存档 (PDF)于December 1, 2017).

- ^ 250.0 250.1 250.2 Golczewski, Frank. Gregor, Neil , 编. Nazism. The impact of National Socialism (OUP Oxford). 2000: 329–330 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0191512032. Prof. Czesław Madajczyk ascribed 2,000,000 Polish-Jewish victims to extermination camps, and 700,000 others to ghettos, labour camps, and hands-on murder operations. His stated figure of 2,770,000 victims is regarded as low but realistic. Madajczyk estimated also 890,000 Polish-Jewish survivors of World War II; some 110,000 of them in the Displaced Person camps across the rest of Europe, and 500,000 in the USSR; bringing the number up to 610,000 Jews outside the country in 1945. (原始内容存档于2020-08-20).Note: some other estimates, see for example: Engel (2005), are substantially different.

- ^ 251.0 251.1 251.2 Longerich, Peter. Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. OUP Oxford. 2010: 748. ISBN 978-0191613470. (原始内容存档于May 21, 2016).

- ^ Phayer (2000), pp. 113, 117–120, 250. In January 1941 Jan Dobraczynski placed roughly 2,500 children in cooperating convents of Warsaw. Getter took many of them into her convent. During the Ghetto uprising the number of Jewish orphans in their care surged upward.[p.120]

- ^ Bogner (2012), pp. 41–44.

- ^ Paul (2009), pp. 16, 63–71, 98, 185. Despite the fact that at least several hundred Sisters of the Family of Mary risked their lives to rescue Jews, only three of them, MotherMatylda Getter of Warsaw, Sister Helena Chmielewska of Podhajce, and Sister Celina Kędzierska of Sambor (see: Sambor Ghetto) have been decorated by Yad Vashem.[p. 84].

- ^ U.S. Department of State. The Tehran Conference, 1943. 1937–1945 Milestones. 2015. (原始内容存档于October 26, 2015).

- ^ ESLI. Property restitution/compensation in Poland (PDF). European Shoah Legacy Institute. July 2014. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于September 6, 2015) –通过Internet Archive.

- ^ 257.0 257.1 Berthon, Simon; Potts, Joanna. Warlords: An Extraordinary Re-Creation of World War II. Da Capo Press. 2007: 285. ISBN 978-0306816505.

- ^ 258.0 258.1 Fertacz, Sylwester. Carving of Poland's map [Krojenie mapy Polski: Bolesna granica]. Magazyn Społeczno-Kulturalny Śląsk. 2005. (原始内容存档于April 25, 2009) –通过Internet Archive, June 5, 2016.

- ^ 259.0 259.1 Slay, Ben. The Polish Economy: Crisis, Reform, and Transformation. Princeton University Press. 2014: 20–21 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1400863730. (原始内容存档于2020-10-02).

The Second Republic was obliterated during the Second World War (1939–1945). As a consequence of seven years of brutal fighting and resistance to Nazi and Soviet military occupation, Poland's population was reduced by a third, from 34,849 at the end of 1938, to 23,930 in February 1946. Six million citizens...perished.[pp.19–20] (See Anti-communist resistance in Poland (1944–46) for supplementary data.)

- ^ 260.0 260.1 Hakohen (2003), p. 70,'Poland'.

- ^ 261.0 261.1 261.2 261.3 Hakohen (2003), p. 70,[5]

- ^ 262.0 262.1 Jankowski, Andrzej; Bukowski, Leszek. The Kielce pogrom as told by the eyewitness [Pogrom kielecki – oczami świadka] (PDF). Niezalezna Gazeta Polska. 4 July 2008: 1–8 [2019-03-19]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-08-26). Also in Around the Kielce pogrom [Wokół pogromu kieleckiego] 2. with Foreword by Jan Żaryn. IPN. 2008: 166–71. ISBN 978-83-60464-87-8.

- ^ 263.0 263.1 Włodarczyk, Tamara. Osiedle żydowskie na Dolnym Śląsku w latach 1945–1950 (na przykładzie Kłodzka) (PDF). Bricha (2.10). 2010. pp. 36, 44–45 (23–24 in PDF). (原始内容存档 (PDF)于April 13, 2016).

The decision originated from the military circles (and not the party leadership). The Berihah organization under Cwi Necer was requested to keep the involvement of MSZ and MON a secret.(24 in PDF) The migration reached its zenith in 1946, resulting in 150,000 Jews leaving Poland.(21 in PDF)

- ^ Aleksiun, Natalia. Beriḥah. YIVO. [2019-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2020-09-22).

Suggested reading: Arieh Josef Kochavi, "Britain and the Jewish Exodus ... ," Polin 7 (1992): pp. 161–175.

- ^ Kochavi, Arieh J. Post-Holocaust politics: Britain, the United States & Jewish refugees, 1945–1948. The University of North Carolina Press. 2011: 15 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-8078-2620-1. (原始内容存档于2020-07-26).

- ^ Marrus, Michael Robert; Aristide R. Zolberg. The Unwanted: European Refugees from the First World War Through the Cold War. Temple University Press. 2002: 336 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-1-56639-955-5. (原始内容存档于2018-02-14).

This gigantic effort, known by the Hebrew code word Brichah(flight), accelerated powerfully after the Kielce pogrom in July 1946

- ^ Siljak, Ana; Ther, Philipp. Redrawing nations: ethnic cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Rowman & Littlefield. 2001: 138 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 978-0-7425-1094-4. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Steinlauf, Michael C. Poland. 1996 [2019-03-19]. ISBN 9780801849695. In: David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig. The World Reacts to the Holocaust. The Johns Hopkins University Press. (原始内容存档于2020-08-19).

- ^ Lukas (1989); also in Lukas (2001), p. 13.

- ^ Albert Stankowski, with August Grabski and Grzegorz Berendt; Studia z historii Żydów w Polsce po 1945 roku, Warszawa, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny 2000, pp. 107–111. ISBN 83-85888-36-5